Can Trump Win Governor of Louisiana?

From their matching red ties to their matching rhetoric, President Trump and Eddie Rispone, the Republican challenger to Louisiana’s incumbent governor, John Bel Edwards, have tried to erase any distinction between them.

“You need to fire your far-left governor,” Trump told the crowd of nearly 14,000 on Thursday night in Bossier City.

“We have to fire our liberal, socialist-leaning governor, John Bel Edwards,” Rispone said when Trump gave him the microphone at the CenturyLink Center.

While it is Rispone’s name that appears on the ballot Saturday for governor of Louisiana, in many respects it is Trump’s reputation on the line, and that is by choice. Trump has injected himself into the governor’s race with unusual vigor, hoping for a state-flipping win that he can take credit for. Unseating Edwards would do a lot to erase the sting of the public impeachment hearings and the news that the incumbent Republican he had backed in the Kentucky governor’s race had earlier Thursday finally conceded defeat. “I really need you … to send a message to the corrupt Democrats in Washington,” a somewhat subdued Trump urged the audience. “So you’ve gotta give me a big win, please. OK?”

But as voters head to the polls Saturday with the race in a virtual dead heat, the risks of Trump’s strategy to make the runoff election a referendum on his own popularity had already become apparent. Early voting turnout in key Democratic districts set records, suggesting that while Edwards has scrupulously avoided tangling with a president who won this conservative state by 20 points in 2016, Democratic voters seem well0-motivated to deliver a rebuke to Trump.

It’s even more challenging for Trump because of an awkward set of electoral facts, starting with the obvious one that Edwards, the so-called socialist Trump wants fired, is actually a deeply conservative Democrat. In fact, he’s a West Point graduate who earlier this year signed one of the nation’s most restrictive “fetal heartbeat” abortion bans, a move that angered progressive Democrats in the state but earned him some credit with conservative Republicans. Add in some Republican softening in the suburbs and a humming economy, which Trump himself praised, and that explains why Edwards approval rating is at 52 percent and his disapproval is in the 30s, more or less mirroring Trump’s own numbers in the state.

“By and large, I think Edwards’ record is an enormous help, and I think it’s why he’s doing as well as he is for a Democratic governor in a deep red state,” said Pearson Cross, associate professor of political science at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette. “His record with regard to getting Louisiana out of endless budget crises, his record in terms of criminal justice reform, giving teachers their first pay raise in years, increasing funding for early childhood education—he can point to these wins and say, ‘Look, I’m making life better for people on the ground here, I have a record.’”

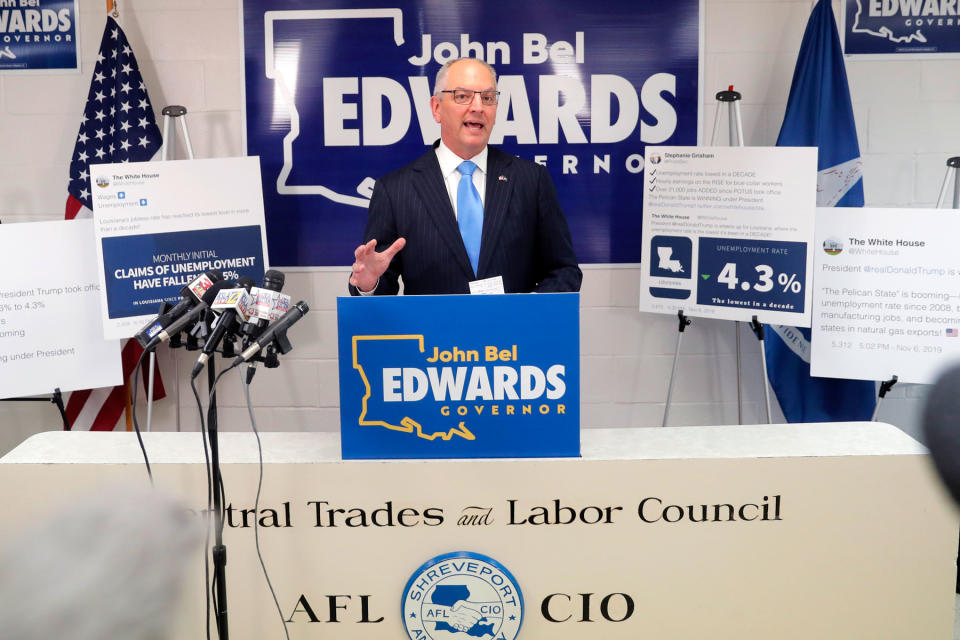

Trump has tried to seize that record, specifically on the economy, for himself, but Edwards is not letting go that easily.

Earlier this month, the White House tweeted: “‘The Pelican State’ is booming—boasting its lowest unemployment rate since 2008, bringing back 5,000+ manufacturing jobs, and becoming one of our Nation's leading states in natural gas exports!”

Edwards tweeted in reply, with only trace levels of sarcasm: “Thank you, I agree. It's taken a lot of hard work, but we're much better off than we were four years ago when I took office. And when I'm re-elected, we'll keep moving our state in the right direction.”

In some respects, Edwards is the only figure in this race who seems determined to frame the race on statewide terms rather than national ones. On top of Trump’s visits (Vice President Pence came before the primary in October), the Republican National Committee this week pumped an extra million dollars into the race. The Louisiana Democratic Party is happy to do what Edwards won’t, running ads on Facebook warning voters: “If Rispone wins, Trump wins.”

***

Edwards’ strategy throughout the race has been to rebut Trump’s acid attacks with heaping spoonfuls of Southern graciousness, at least where the president is concerned. When he was asked at a recent event what he thought of Trump’s regular forays to the state, he maintained his policy of nonaggression.

“This is the political season, and he is coming here because his party expects him to, he’s doing what’s expected of him, and its a very political trip into Louisiana,” Edwards said. “Obviously, he’s the president, he’s welcome here any time.”

And then just to remind voters how close the working relationship is with the administration, Edwards talked about the nine times he was invited to the White House to meet with Trump on issues like transportation infrastructure, the opioid epidemic and criminal justice reform.

“Edwards has been an elusive target in terms of being someone President Trump can attack,” said John Couvillon, who worked on Republican Rep. Ralph Abraham’s congressional campaigns as a pollster in 2014 and 2016. “He has totally shied away from any kind of mention about President Trump and impeachment, and he has avoided picking any overt fights with the White House.”

That goodwill is quite a bit less evident when Edwards talks about his challenger.

On Wednesday, Edwards met with voters and artists at Studio BE, in a warehouse in New Orleans’ Bywater neighborhood. He touted his local successes: Medicaid expansion, funding for education, low unemployment. He made a point of reminding his audience about Rispone’s previous criticism of New Orleans, an anti-urban talking point that Trump has made a staple of his attacks on Democratic leaders.

“[Eddie Rispone] asked me at our one and only debate in the runoff, ‘Why do you support New Orleans which is a sanctuary city?’ And my response was, ‘that’s a stupid question,’” Edwards said. “You support New Orleans because it’s a city in Louisiana that’s incredibly important to our state.”

Orleans Parish, which went 80 percent for Clinton in 2016, is one of the four parishes where early turnout has hit record levels for a nonpresidential year. Perhaps it is a chance to exact some political retribution against Trump that has motivated those voters. Edwards, though, has stuck with a critique of Rispone that hearkens back to recent Louisiana history, not national history.

“[Eddie Rispone] is trying to nationalize this race because that’s the only shot he has,” Edwards said. “He cannot win this race based on Louisiana issues because he hasn’t demonstrated any knowledge about how state government works, he doesn’t have any vision for the state of Louisiana, and to the extent that he has spoken in any specificity about his policy proposals they sound an awful lot like warmed-over failed policies of [former Governor] Bobby Jindal that ran our state so deep into the ditch.”

That ditch included a $2 billion dollar budget deficit and cuts to higher education funding—both of which Edwards reversed in his first term. Louisiana now has a budget surplus, and education funding has been restored.

Perhaps the most significant item on Edwards’ score sheet is expanding Medicaid. After Edwards’ predecessor, Republican Governor Bobby Jindal, refused to accept the Medicaid expansion offered by the Affordable Care Act beginning in 2014, it was one of the first things Edwards did when he was sworn in to office in 2017.

“And, bang, around 480,000 people who didn’t have health insurance got it. That’s unbelievably huge, that’s over 10 percent of the state population,” said Pearson Cross. “Not to mention roughly $12 billion in federal money coming to Louisiana as a result of Medicaid expansion. It was a no-brainer. You look at, well, we had a Republican governor who didn’t do that—Bobby Jindal—you want to go back there?”

Rispone has said, if elected, he would “freeze” Medicaid enrollment—potentially affecting the coverage of seasonal or shift workers, and effectively killing the program. In Kentucky, outgoing Governor Matt Bevin also threatened to cut Medicaid expansion in the state—which would have likely cost 400,000 people access to health insurance. Democratic Governor-elect Andy Beshear has promised to protect Medicaid in Kentucky (and, like Edwards, has promised a pay raise for teachers).

The scarlet letter on Edwards’ résumé is that he’s a Democrat in the deep red South. Successful record or not, he belongs to the wrong party—something Rispone and Trump hope to capitalize on. Rispone “says he wants to do what Donald Trump has done for the nation here in Louisiana,“ Cross said, “and that’s a message that resonates.”

Rispone—like Trump—is a businessman. His engineering and construction firm has made him one of Louisiana’s wealthiest citizens. He takes every opportunity—at debates, in commercials and at campaign appearances—to remind voters that he is not a career politician.

“Rispone doesn’t have a public profile, and he’s never held public office before, so when he announced [his candidacy] and released his first set of commercials, he made it clear that he was an ardent supporter of President Trump,” said Dr. Silas Lee, professor of public policy at Xavier University of Louisiana. “And considering this is a very red state that is very conservative on many issues, that made sense.”

“To the extent that Rispone has been successful at claiming the Trump mantle,” Cross adds, “I think he will be successful with many Republican voters in Louisiana, and conservative voters and people who like Trump.”

***

In the end, the race will likely be decided by supporters of Republican Rep. Ralph Abraham, the man who finished third in the October primary.

The final results of the October 12 primary had Edwards at 46.6 percent. Rispone, at 27.4 percent, edged out Abraham at 23.6 percent, to qualify for the runoff. Cross says those results indicate that Edwards is exceeding expectations for a Democrat in Louisiana.

“The baseline for Democrats in Louisiana, regardless of who’s running, is around 39 percent,” Cross said. “That was about what Barack Obama got; that was almost exactly what Hillary Clinton got; that’s typically what candidates get in statewide elections when you have one Republican and one Democrat.”

You could also look at those numbers and assume that, if the two Republican candidates hadn’t split the vote, one of them could have pulled 51 percent and won the election outright.

But Michael Henderson, director of LSU’s Public Policy Research Lab, says this election is not all about partisanship. “If it was, Edwards would have plummeted all the way down to about 40 percent of the vote, instead he’s still able to be in the upper 40s, so it’s within reach for him to get a win,” Henderson said. “So that appeal, that messaging that he’s doing, has worked to some extent so far. He can’t get that close to the 47 percent vote that he got in the primary without crossover support. The question is can he now build on that and get some of folks who might have voted for Abraham in the first round to switch their vote to him in the second round—and that’s a harder thing to do.”

Many of the people who voted for Abraham in the first round live in Louisiana’s 5th Congressional District. This rural district covers most of the northeastern and central portion of the state; it is also Abraham’s home district.

“In a rural district, people know their elected officials personally,” said John Couvillon. “In the case of Ralph Abraham, he was the vet who treated their animals and the doctor who treated their children,” before he became their elected representative.

The predominantly Republican district went for Trump by a margin of 29.4 points in 2016 (by comparison, Trump won Louisiana by 19.6 points), and provided a strong bloc of support for David Vitter over John Bel Edwards in the 2015 gubernatorial race.

With Abraham out of the race, the big question is: Where do his voters go? Do they go to Rispone, switch support to the conservative incumbent, or do they stay home?

That could depend on whether or not Rispone’s actions in the primary remain fresh in voters’ minds.

“There were some pretty bitter feelings between Rispone and Abraham. Many people thought that Rispone broke the Republican rule by directly attacking a fellow Republican in a race against a Democrat,” said Cross.

The political attack ads came in the weeks leading up to the primary, with Rispone trailing Abraham in the polls. Rispone painted Abraham as a liar, a Trump critic and a supporter of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

“If you’re attacking Ralph Abraham, the people who are his constituents are much more likely to take umbrage because they know Ralph enough to where they don’t believe for a second that he’s a Nancy Pelosi clone or he’s opposed to the president,” Couvillon said.

After the primary, Abraham quickly stepped in line and announced his support for Rispone—but he appeared with Rispone at only two campaign events: in Abraham’s hometown of Monroe with President Trump and on Thursday with most of Louisiana‘s Republican members of Congress.

“There’s the question of how much lingering resentment there is against Rispone’s attacks on Abraham,” Couvillon adds. “Rispone needs 90 percent of the Abraham vote [to beat Edwards], which is a pretty tall order.”

Meanwhile, Edwards needs only about 10-15 percent of Abraham’s voters to win reelection. Analysts don’t expect those votes to come from one specific part of the state.

“You can’t really make generalizations about which area is going to go more for Edwards,” said Cross. “I think it’s going to be an individual voter thing.”

Edwards will be looking to pick up some of those individual voters in St. Tammany Parish, a traditional Republican stronghold that sits across from New Orleans on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain where he performed well in the primary.

“The classic Republican constituency is this one that we’re seeing nationally start to shift—suburban, college-educated, middle class voters. That’s St. Tammany Parish now,” said Michael Henderson. “They’re more for Edwards than you might have guessed.”