‘The truth is one thing’ — a conversation with Mitch Albom

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“What’s the biggest lie you’ve ever told in your life?” Mitch Albom, the bestselling author and columnist, has been asking people recently. He rarely gets an answer.

“Many of them,” he tells me, “don’t want to share it with me.”

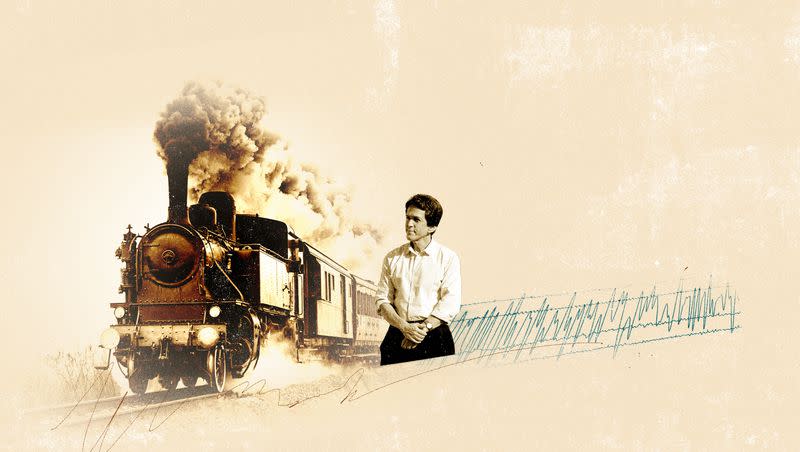

We’re talking a few weeks before the publication of “The Little Liar,” Albom’s novel about a child who is tricked by the Nazis into reassuring Jewish families that it was safe to get on trains headed to Auschwitz, and the lifelong repercussions that play out for four people because of that lie. It is an eerily prescient book, landing at a time in which the world is freshly focused on the horrors of the Holocaust.

But it is, foremost, a book about trust and deceit, and how “the big lie” is not just a tool of politicians and dictators, but an insidious worm that can burrow into all of us, even if its genesis was benign.

When people uncomfortably duck Albom’s question, he offers them an out: “I say, ‘Don’t share it, but just ask yourself: What would you do if you could make that lie go away? What would you do to be forgiven for that lie?’”

There’s no small talk with Albom, who is not one for ducking hard conversations. It was, after all, a series of hard conversations that catapulted him from a popular Detroit sportswriter to an internationally acclaimed author after the publication of “Tuesdays with Morrie” in 1997.

Now among the bestselling memoirs of all time, the book chronicles Albom’s weekly visits with Morrie Schwartz, his former Brandeis University professor who was dying of ALS, and the wisdom gleaned in their conversations. The book, which sold more than 18 million copies and was made into a movie and a play, changed the trajectory of his life and continues to shape Albom’s work at age 65. His podcast, for example, is called “Tuesday People” and many of his subsequent novels revolved around things he learned from Schwartz. A 25th-anniversary edition was released last year, and people are still bringing him worn copies for him to sign.

In an interview last year with Ted Koppel, who appeared to be baffled by the book’s enduring popularity — “You’re a good writer, but you’re not Mark Twain,” Koppel said — Albom said, “Most people in life, no matter how happy they look on the outside, are walking around with a piece of a broken heart.”

The lessons in “Tuesdays with Morrie” offer a path forward when our outward circumstances seem hopeless, which is one reason the book continues to resonate.

But right now, with Israel waging war with Hamas and antisemitism on display worldwide, there is an urgency to the themes of Albom’s latest book, which goes on sale this week. He spoke with Deseret about the challenges of writing “The Little Liar,” the human struggle to find truth and trust, and how “Tuesdays With Morrie” upended the plans he’d made for his life.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Deseret News: When you started writing this book, you had no idea that the world would be on fire as it is right now with the events unfolding in Israel and Gaza.

Mitch Albom: I had no idea when I started this book what would be going on in the world, and I had no idea when I finished this book many months ago. But I did think when I wrote it that it was a pertinent book for our time, not because of anything in the Mideast, but because of how we are currently treating the truth. How it seems like people are just sort of adopting their own truth and saying, “That’s it, I don’t want to hear anyone else’s perspective. I’ve got support from other people who believe what I believe, and that makes it the truth.”

But that’s not what the truth is. The truth is empirical. The truth is one thing. And yet, in our country, we tend to retreat to our corners and say we’re only going to look at the events of the world through this lens or through that lens. And that can distort the truth greatly.

I wanted to write a story that showed the lies that we tell in our lives, and how we spend much of our lives trying to get forgiveness for the lies that we tell. Nico (the child in the book) ends up trying to spend the rest of his life trying to be forgiven for the lies that he told, and I think that’s true for a lot of us.

So I thought I had a book that would be meaningful to people no matter what. The fact that it now has come out at a time when Jews are being slaughtered and intimidated and persecuted and commented on hatefully, I’m sure there are a lot of people who will read the book and see how that happened in a place, where the book is set — Salonika, Greece — that was at the time, just before the war, a majority Jewish city. Think about that. A city where the majority religion was Judaism, and yet the Nazis were able to come in and in less than a year, wipe out the majority population of that city. So when you look at a place like Israel, which is majority Jewish — people say, Israel will always be safe, Israel will always be there — well, a lot of Jewish people aren’t so sure.

DN: What kind of research did you do? Did you go to Greece while you were writing?

MA: Not only did I go to Greece, I lived in Greece when I first got out of school, I was a musician living in Greece; it’s not a story that’s often told in my bio.

I was familiar with Greece, I spoke a little bit of the language, and I knew a little bit about the history there. And when I decided I wanted to write this book, I purposely didn’t want to set a story in Poland or Germany or France, where so many fine books have been set. But a lot of people didn’t know Greece was involved.

I grew up with a lot of background about the Holocaust; there are survivors in my extended family of concentration camps. Where I grew up in New Jersey, there were people on my block who would always wear long-sleeved sweaters or shirts, during even in the hot summer weather, and I once asked my mother, “Why are these people always wearing long sleeves?” and she said, “Well, they have these numbers tattooed above their wrists and they’re self-conscious about people seeing them.” That was the first indication that people went through something so horrifying, and obviously I learned a lot more about it as I grew up.

Then I did an extensive amount of research, and most of the stuff that takes place in World War II in the book is accurate, except the characters are obviously fictional. I’ve never written what they call a historical fiction novel, so I don’t know what the rules are for it — I don’t know if this qualifies, but I think it comes pretty close. For example, there’s a scene in Liberty Square where Jewish men are forced to do calisthenics for eight or nine hours in the hot sun, and if they stop, they get beaten or attacked by dogs … that’s all true, even that people were taking pictures and laughing, that all comes from accounts of the events. I endeavored to be as realistic as possible while still recognizing that it’s a novel, and it doesn’t all take place during the Holocaust. In fact, more of the book is in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, when these children grow up, and the price that is paid for what happened.

DN: On one hand, we seem to live in a confessional society, but as you make clear, lies hold a lot of power — not only over other people, but over us.

MA: It’s a pretty interesting thing about human nature. We are the only creatures on Earth that verbally tell lies, unless there’s some bird that has a different chirp that I’ve never heard of. The damage that we do with our lies is pretty interesting, and of course, the damage on a grand scale … Joseph Goebbels had a brilliant quote, I just wish he wasn’t the one who said it: A lie told once is easily seen as a lie, a lie told a thousand times becomes the truth. That’s the real consequence of wide-scale lying; it’s adopted as the truth and not even questioned anymore.

DN: “The Little Liar” is a book about lying and its consequences, but isn’t it also a book about trust, which is something else we seem to have a problem with in contemporary American society?

MA: Yes, for sure. Who do you trust? This little boy trusted that he was being told the truth because he lived in a world where he only told the truth. And his friends and community and loved ones believed he was telling them the truth and trusted that he was telling them the truth because he’d never lied before. Sadly, even during the Holocaust, even during the worst treatment by the Nazis, there was still this trust by many of the Jewish victims that it couldn’t possibly be as bad as it seemed, that people in the end would do the right thing.

So even as they were in the ghetto and about to be taken to these trains, the Germans came to them and said, ‘You’re going to Poland and they’re not going to accept Greek drachmas, so give us your money and we’ll give you a receipt, and when you get there, you hand over this receipt and you’ll be able to get Polish currency.’ And people did it, even after being chased from their homes and chased from their businesses and put in a ghetto. People want to trust, they want to believe in a better outcome. I found that to be so heartbreaking, that human desire to trust is always there and yet it was so abused.

DN: Why do you think we have a desire to trust? Certainly our evolutionary history suggests that we should not have it, that perhaps we should be distrustful of other people.

MA: Along with the fight-or-flight instinct that was put in us when we were created, I think there is a desire to be loved. And a desire to love back. And those things are frequently at odds with each other. Instinctively, we have this thing that sets off an alarm — run, run, it’s dangerous — on the other hand, we also instinctively want to be loved and accepted, we want to feel love and give love. That’s what my old professor Morrie Schwartz used to call the yin and the yang of it, the tug of war that goes on inside everybody.

DN: In your 20s, when you were a sportswriter, what were you hoping in your wildest dreams that you would achieve? And at what point did you realize your path might be a little bit different?

MA: I was a musician first, but when I got into sports writing, my only dream was to be the best sports writer in the country, the most recognized sports journalist that I could be. And I pursued those ambitions for the better part of 13 years or so, until I was 37 years old and I was doing pretty well at them. And then I encountered my old professor, Morrie Schwartz, who was dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease, and I absolutely planned to return to sportswriting, but I went and saw him one Tuesday, and then another Tuesday, and he kept saying come back, and so six days a week, I was a sportswriter and one day a week, I was a confidante to a man who was dying. And I wrote a book to pay his medical bills, and I planned to return to the world of sports.

I think they printed 20,000 copies for the world ... they didn’t expect anyone to buy it, and I certainly didn’t. Nobody wanted it when we went around to different publishers. And then a crazy thing happened … people started to read it, and they passed it on, and more people read it and more people read it, and it became this sort of phenomenon that I still don’t really understand.

And people began to talk to me differently. And for me, this is where the transformation really took place. Instead of wanting to talk about the Super Bowl, which is pretty much what everybody wanted to talk to me about before, people would stop me and say, “My mother died of cancer, and the last thing we did was read your book together. Can I talk to you about her?”

This started to happen two times a day, four times a day, every airport, every place I went, if I spoke, if I signed books afterwards, that’s all I would hear — stories of grief, stories of people reuniting, stories of forgiveness. And slowly my world began to become about that. And wherever I went, people wanted to talk to me about that. So when it came time to finally write another book, I never even thought about doing a sports book again. I wrote a book called “The Five People You Meet in Heaven,” a novel, and I did that because I knew if I wrote a nonfiction book, it would pale in comparison to “Tuesdays with Morrie.”

DN: Can you tell me a little bit about your writing schedule and how you juggle it with your charitable work and the orphanage that you run in Haiti? Is there an expectation from your publisher and agent that you write a certain number of books in a certain time frame?

MA: Well, there’s a desire. (Laughs.) But the desire does not always meet the expectation on their part. I usually need a break. These books take a lot out of me. And usually I’m pretty exhausted after they’re done. Plus, I have all these other things. The orphanage is three full-time jobs, and I’m there every month, one week out of every month is already gone, and the other three weeks are dealing with the issues from the orphanage here. I’ve got 12 kids (from Haiti) who are now here in college and one in medical school — it’s a lot to keep up with. It’s quite a big family, and I’m not in any way complaining. I love it. I’m thrilled to have the privilege, at this age ... we have three children with medical issues living in our house now — a 1-year-old, a 4-year-old and a 6-year-old — and it’s delightful. I love waking up to all the noise and the squealing. You don’t usually get this at my age. But it keeps you from writing.

So I’ll return to that at the beginning of next year. But I’m pretty disciplined when I start. I work every morning, but only for about 3-3 ½ hours, and then I come back the next day and do it again. I’ve learned that I could sit in front of a computer or typewriter for eight or 10 hours a day and I wouldn’t get any more than the first three hours of it. That’s when the gas runs out of the tank.

DN: Is there anything you would like to say to our readers that I haven’t asked … about truth, about trust, about the world?

MA: There’s a parable in the (new) book that I thought was very telling. Before God created man, he consulted with his angels and asked if it was a good idea. And Righteousness said, “Yes, create man, man will be righteous,” and Mercy said, “Yes, create man, man will be merciful.” And all the other angels said yes, except Truth. Truth said, “Don’t create man because man will lie and destroy me.” And God took all this counsel into consideration and threw Truth out of Heaven and down to Earth. And there’s a lot of interpretations of that — why God threw Truth out and didn’t accept what Truth was saying, but it might be that God did accept what Truth was saying and knew that it was a precious and vital thing, and so He cast it down to Earth to be inside all of us.

And I think inside all of us, we know what the truth is. And we know how it feels when we tell the truth and how it feels different when we tell a lie, even if we tell little lies. At this time in our history, we need to understand that the little lies lead to bigger lies and and big lies lead to really big lies. And that the world is in the balance with the way we are going to acknowledge truth in our lives. Our futures, our kids’ futures, hang in the balance on that question.