A tsunami in Jasper? How falling ice nearly caused a 'mass casualty' event

Picture a wall of water suddenly rushing down a mountain valley towards you, giving you just seconds to react.

That’s just what happened in 2012 at Mount Edith Cavell in Jasper National Park when the hanging Ghost Glacier fell into the glacial lake below.

Luckily, in a part of the park that could be filled with thousands of outdoor enthusiasts on an average summer day, this glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) happened at night.

“We would have called it a mass casualty incident had it happened during the day in the summertime,” said Parks Canada senior advisor Steve Blake, who was a visitor safety supervisor in Jasper National Park in 2012. “We’re very fortunate it happened overnight.”

A photo taken hours before the Ghost Glacier fell is compared with a photo taken after. (Parks Canada)

SEE ALSO: Picturesque B.C. glacier is undergoing dramatic changes, what it means for us

Sometime between August 9 and 10, approximately 125,000 cubic metres of melting, destabilized ice fell from the north face of Mount Edith Cavell, according to a Parks Canada report on the incident. Eventually, it tumbled into a tarn (glacial mountain lake) below that was full to overflowing thanks to recent rain and snowmelt, according to a Parks Canada report on the incident.

Chunks of ice over four metres high, weighing as much as 80 metric tonnes, were lifted out of the lake and carried downstream as a massive volume of water was displaced. Close to a parking lot downstream, surge marks on trees indicated the water was at least 1.6 m deep.

Asphalt was lifted from the ground and left folded and sagging as the water made its way down the drainage channel. An outhouse was swept away by the rush, while a picnic area was left hidden under rock and gravel. Boulders were found on the road leading up to the parking lot, which measures a metre across.

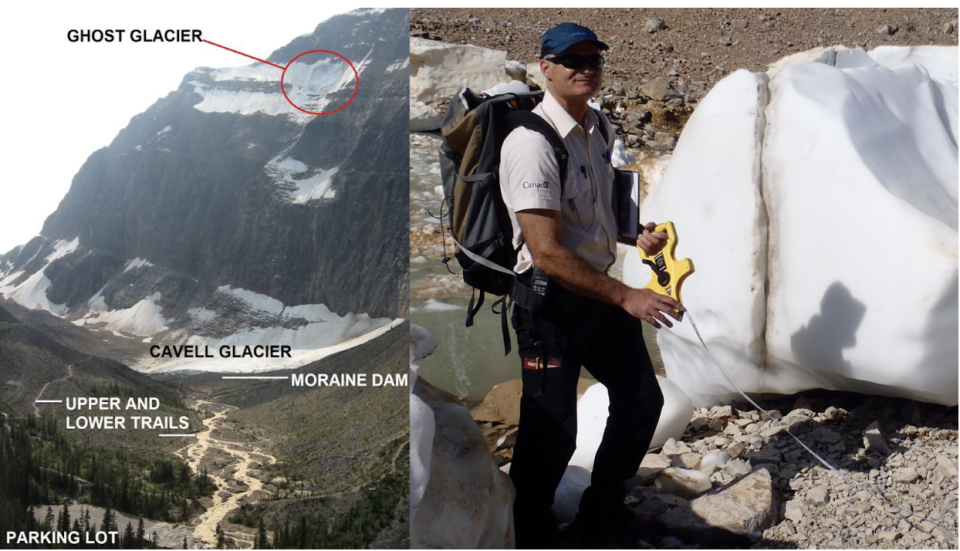

(Parks Canada)

SEE ALSO: Calgary is preparing for an even bigger flood than 2013

Trees were uprooted, existing drainage channels were eroded, new drainage channels were created, and the depth of the tarn, which is believed to have been nearly 40 metres deep before the GLOF occurred, was reduced by as much as 11.8 metres. Evidence of damage from a wind blast was discovered as well.

Fortunately, a search and rescue team was able to determine the next morning that nobody had been affected by the GLOF.

Prior to the event, there was a "high-use" trail that led from the parking lot to the tarn, according to the report, which also posits that “on a busy day in August, upwards of 100 people” may have been on that trail at any given moment.

A researcher measures an ice chunk found downstream of the tarn. (Parks Canada)

While this historic incident is unique to Canada, research suggests that as rates of glacial melt accelerate thanks to climate change, the risk of GLOFs is increasing worldwide.

One study found 15 million people are at risk around the globe, with the highest danger in Pakistan, China, India, and Peru, thanks to high concentrations of glacial lakes (which are getting larger as glaciers melt) and population concentrations along drainage channels nearby.

RELATED: Record nine metres of melt observed on Alberta’s Athabasca Glacier

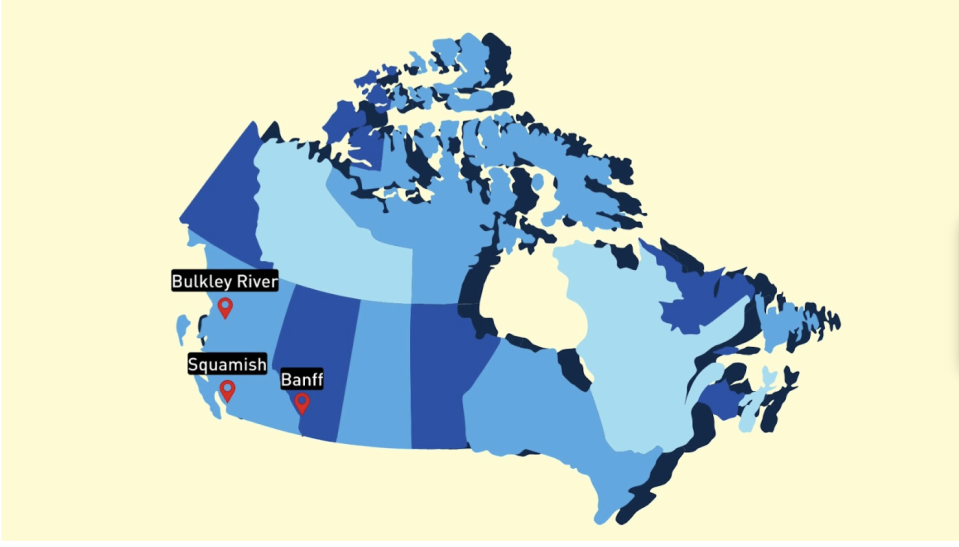

The report also found Canadian communities like Banff, Squamish, Victoria, and the Bulkley River region are at some risk of being impacted by GLOFs due to the proximity of nearby glacial lakes, although the study didn’t assess the likelihood of a GLOF occurring at any location.

“Areas that currently don’t have much risk because they don’t have many lakes will steadily become more risky because the glaciers are melting and forming lakes where we don’t currently have them,” said co-author Tom Robinson.

“We would anticipate that these floods might be much larger in the future simply because there’s more water stored in the lakes.”

The Parks Canada report on the Ghost Glacier GLOF concludes that “future infrastructure development will benefit from the knowledge and the warning that this type of event is possible and may be on the increase with predictions of climate change.”

Blake said he isn’t personally aware of any other looming threats in Jasper National Park, in part because the combination of a hanging glacier, large lake and popular visitor centre is rare, though he said some risk remains in the area as another glacier still feeds the tarn.

Since the event, the parking lot, trails, and adjacent facilities have been relocated out of the runoff zone of the tarn, Blake explained.

Brian Menounos, a research professor at the University of Northern British Columbia, suggests that, given the fact that most of Canada’s glaciers are remote, the increasing popularity of outdoor adventuring might pose a bigger threat than climate change.

“People love the high mountain environment in Western Canada,” he said. “At face value, the risk slowly starts to increase as more and more people get into the backcountry.”

Either way, the idea of whether or not risk is increasing is one the Canadian government is showing some interest in exploring.

The Geological Survey of Canada is in the midst of a research project examining the geohazards associated with deglaciation in alpine environments. GLOFs are among the risks being considered as the research, being conducted in BC’s Joffre Lakes Park, is completed.

“What we’re trying to understand is, as the glaciers recede and the permafrost in the rock walls degrades, how does that increase the likelihood of large alpine landslides occurring, and what are the downstream consequences of that?" said research scientist Jeff Crompton, who works within the Geological Survey of Canada branch of Natural Resources Canada. “What are the hazards?”

Explaining that in some cases, alpine permafrost can act as “the glue binding a mountain together”, Crompton said a potential increase in the frequency of large landslides in BC helped form the impetus for the project.

For example, large slides occurred in the Ecstall River area in 2022, at Elliott Creek in 2020, and at Joffre Lakes Park in 2019. Others have occurred in places like Alaska during that time frame as well.

“It’s just alarming to see such large events happening basically every summer,” said Crompton.

The Joffre Lakes landslide, which occurred on the north face of the mountain, displaced as much as 5 million cubic metres of rock.

“If the landslide had happened on the other side of the mountain, into Joffre Lake—I mean, this is one of the most heavily touristed areas of the south coast,” he said.

The project began in 2022, is bringing together experts in glaciology, hydrology, and seismology, and is slated to be completed over about five years. Crompton hopes it acts as a pilot project for further, more widespread research into GLOFs and other hazards that might exist in Canada’s mountain environments.

“What we learn from Joffre, we’re hoping to be able to carry out into larger areas into the south coast mountains and Rocky Mountains,” he explained.

“What we really need to be able to do is pull together the data from sites across the coast mountains and rocky mountains and try to integrate various data sets and start putting together more regional assessments of what mountainous areas are at risk of these large events.”

WATCH BELOW: Alberta glacier's rate of melt this past year stuns researchers

Header image courtesy of Parks Canada