Tucson's streets can be deadly for pedestrians. Here is what the city is doing

Tucson has some of the most dangerous roads for pedestrians in the U.S.

Last year, the Tucson Police Department recorded 95 fatal car crashes, up from 90 in 2020, according to state data. Of those deaths, 29 were pedestrians, 7 were cyclists, and 39 were drivers or passengers, according to data collected by advocacy group Living Streets Alliance.

Tucson also ranked sixth in 2020 on a list of 50 American cities with the highest rate of motor vehicle crash fatalities, gathered by Stacker using U.S. Department of Transportation data. It was among the top cities on that list in terms of pedestrian fatalities from vehicle crashes, both in terms of raw numbers and rate per 100,000 residents.

Zooming out to Pima County data that encompasses other cities in Tucson's metro area, 48 pedestrians were killed by cars in 2023, while another 72 pedestrians were killed by cars in 2022.

Why are so many pedestrians dying in Tucson?

One major factor impacting pedestrian deaths is infrastructure and street design, according to experts and elected officials.

The large, multi-lane roads with few crosswalks and higher speed limits, also called arterial roads, are where most of the fatal car accidents take place.

Evren Sönmez, director of strategic policy and practice at nonprofit Living Streets Alliance, said the number of deaths is unsurprising, given how many large arterial roads crisscross Tucson.

She noted that data only tells part of the story.

“Those numbers are already alarming, and in addition to that, there are thousands of people who are seriously injured; the data doesn't reflect that,” Sönmez said.

Tucson Councilmember Steve Kozachik said while high speeds, unprotected left turns, and poor lighting are some of the major reasons for Tucson's high traffic fatality numbers, people crossing roads while intoxicated is also a factor.

"We have a lot of people who are just high and they walk out in front of a car in the middle of the night ... that has to be a part of any narrative about traffic safety, about safety on our roadways, is that some of the burden shifts to the pedestrians and the bicycle riders also," Kozachik said.

Officials ran toxicology screens on 37 of the 48 pedestrians killed in 2023 in Pima County. The region's Medical Examiner's Office data shows 68% of those victims tested positive for methamphetamine, fentanyl, alcohol, or other drugs of "significant interest," not including marijuana. For Tucson, officials ran toxicology screens on 30 of 39 pedestrians killed in 2023, with 73% testing positive for drugs or alcohol.

Sönmez preferred to keep her focus on street design.

Living Streets Alliance collected public data showing where traffic fatalities occurred in Tucson from 2017 to 2024. Sönmez said that data from 2017 to 2022 revealed most of the fatalities occurred on streets with speed limits above 35 miles an hour, like arterial roads where speed is prioritized over pedestrian safety. Arterial roads include streets like Grant Road or Broadway Boulevard.

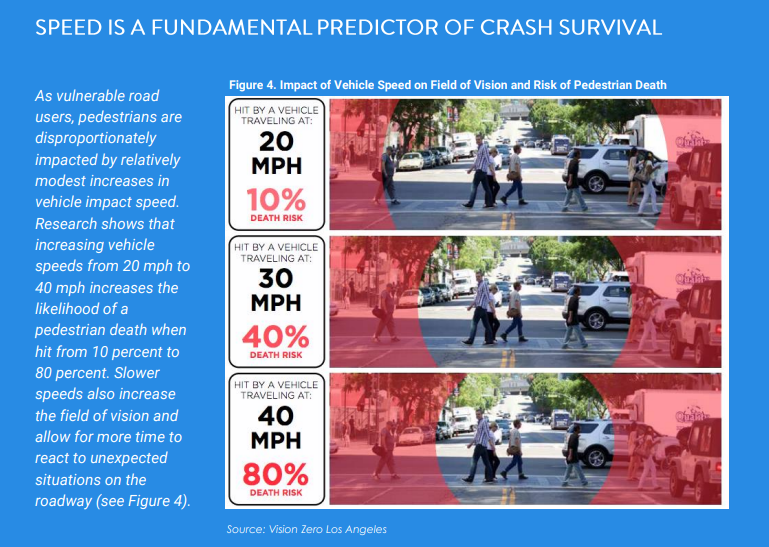

According to Tucson’s Pedestrian Safety Action Plan, if a pedestrian is hit by a vehicle traveling at 20 mph, they have a 10% risk of death. That number skyrockets, with the risk of death at 80% if a vehicle is traveling at 40 mph.

This year, Tucson has already had 12 traffic fatalities as of Jan. 29, according to the organization’s data. Nine of them were pedestrian fatalities.

One of the issues with Tucson's primary roads is they have aspects of open roads, where speed is prioritized, combined with roads where people are crossing to reach their destinations, Sönmez pointed out.

“If you think about those arterials, that's also where all of our destinations are,” she said. “People are getting to the grocery store, getting to the bus stop. There are people walking across the street to get to places.”

Data from the city shows from 2014 to 2018, 49% of crashes occurred on arterial roadways. The city said that figure "far outweighs" their relative proportion — arterials make up only 3% of roads in Tucson.

What does a safe street look like?

Sönmez said safer streets are different than the large, expansive, higher-speed roads. Neighborhood roads are engineered to signal cars to slow down, with crosswalks, traffic lights, and narrower streets.

Sönmez said Congress Street, downtown Tucson’s main corridor is an example of a road that prioritizes safety over speed.

“When you enter that downtown environment with two lanes of traffic, with frequent traffic lights, lots of people around close to the street, wider sidewalks with things that encourage human activity … it encourages a lot more caution,” she said.

The number of traffic fatalities is not only an issue in Tucson but also some states nationwide. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimated in the first half of 2023 that traffic fatalities have increased in 21 states and Puerto Rico compared to the same period in 2022.

What solutions has Tucson proposed?

Tucson has taken several steps to address the problem, including starting to move away from road widening as the means to improve traffic corridors, Sönmez said.

The city identified key strategies to improve pedestrian safety in its Pedestrian Safety Action Plan. Some of the engineering solutions proposed by the plan include reducing vehicle speeds, enhancing pedestrian visibility, improving motorists’ yielding behavior, providing frequent crossing opportunities for pedestrians, and reducing pedestrian exposure to traffic.

The Tucson City Council in 2019 adopted the Complete Streets Policy, which guides the development of transportation and mobility, prioritizing various street improvements like bicycle boulevards, protected bicycle lanes, high-capacity transit, accessible sidewalks, walking paths and more.

According to the Complete Streets Policy, road widening should only be pursued “in limited circumstances.” It noted while road widening offers opportunities to incorporate many Complete Streets elements, “overly-wide roads can also be a barrier in the city."

Mayor Regina Romero was vocal about finding a solution for traffic fatalities a year before the policy was adopted, when she was serving as a city council member.

With 62 deaths in 2017, she felt the city was not doing enough to solve the issue and it needed to implement a plan. In a January 2018 meeting, she reiterated the need for infrastructure to improve areas where pedestrians and cyclists were often killed.

"A lot of them (traffic fatalities) are simply accidents. A lot of them, there is drinking involved, but if we, as a mayor and council, can do something, especially an action plan to help prevent this, I think we should take action," she said.

Romero did not respond to The Arizona Republic's request for comment on this story.

In the four years since the policy was implemented, advocates say that while conversations about improving road safety are taking place, change is not happening as quickly as it should.

“In terms of follow-up implementation plans and procedures, there's been a lot of movement in that front, but we haven't actually seen anything in the ground,” Sönmez said.

Kozachik agreed that the implementation of the policy has been slow, primarily due to the public input process. He used his ward's discretionary funding to put in traffic-calming structures like chicanes, speed humps and roundabouts.

"I'm not waiting on the slow rollout of the Complete Streets initiative to use some of the ward dollars that we've got to work on troublesome areas within the ward itself," he said.

He said data shows high-speed limits can be fatal, and the city has worked to decrease those limits on bicycle boulevards. That's meant advocating for more people to use the bicycle paths in certain areas and showing the state that conditions in these areas have changed.

"I would like to see us across the board drop speeds in our major arterials and our collector streets by five miles an hour ... We have some restrictions on what we can do locally in terms of lowering speed limits," he said.

Reach the reporter at sarah.lapidus@gannett.com. The Republic’s coverage of southern Arizona is funded, in part, with a grant from Report for America. Support Arizona news coverage with a tax-deductible donation at supportjournalism.azcentral.com.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Tucson's streets are deadly for pedestrians. Here's what the city is doing