TupaTalk: Lou and Louis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Some nights a comet flies

Some nights the silence sighs

Some nights all hope seems gone;

all nights lead to the dawn.

—

More:TupaTalk: Vince Lombardi set standard as coach, competitor

A decade ago, I interviewed two remarkable men — Lou Brissie and Louis Zamperini.

Both displayed remarkable athletic skills growing up. Both fought in World War II.

Each suffered incredible hardships from their military service, but returned to live honorable lives.

I didn’t really have any specific reason to talk to them in terms of local sports.

The desire to talk to two such great and courageous men that are are part of our generation persuaded me to try.

Lou Brissie — a left-handed pitcher — was only 17 when Pearl Harbor suffered its invasion. Brissie already had started his semipro baseball career before he enlisted in 1942 in the Army.

A couple of years later, his left leg was nearly blown off by an artillery shell.

Doctors planned to amputate the limb, telling him it was beyond repair and could threaten his life. But, Brissie begged the doctors to operate instead.

I think he told me endured more than 15 or 20 operations to to try to put his leg back together so that he could play baseball. But, he still had to wear a metal brace on his leg.

Serendipity gave Brissie his first big break when Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack — who had scouted Brissie prior to the war — signed him up in 1946.

The 23-year-old Brissie spent most of 1947 in the minors, building his credentials and following the program he and Mack had agreed on in order to give him a chance to pitch for the big club.

The A’s put Brissie on their roster to start the 1948 campaign. Mack gave him his first start against the Boston Red Sox — which featured Ted Williams.

Williams stepped up — and lined a bullet off of the brace on Brissie’s injured leg.

Brissie fell like a metal duck in a shooting gallery. He writhed in agony few of us will — thankfully — ever experienced.

He told me that as soon Williams touched first base he was the first one to sprint to the mound and offer encouragement to Brissie.

During those moments, Brissie could have called it quits for that game — and his dream.

But, he got up, everyone went back to their places, he climbed the mound and he faced the next batter. And the next one. And the next one.

Brissie went the complete game and pulled out the win, 4-2 — after striking out Williams for the final out.

Brissie went on to win 44 games in a career that covered part or all of seven seasons.

He went on to oversee the national American Legion Baseball program.

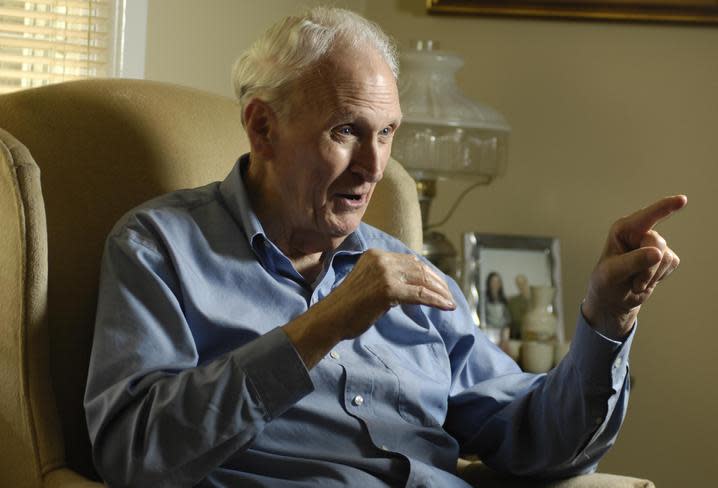

Lou was 88 when I somehow found a contact number and spoke to him via phone.

He was gracious and interesting. It was a privilege.

More:TupaTalk: In the long run, winning effort is the only thing

Louis Zamperini’s odyssey is wonderfully chronicled in a Laura Hillenbrand book, whose short title is “Unbroken.”

Many you might have also seen the film “Unbroken,” and another movie that followed.

Louis proved delightful to chat with as I tried to focus on specific details in his experiences in order to try to make it a meaningful interview. He offered profuse praise about the effort Hillenbrand had made to painstakingly get the story right and tell it an expert’s touch.

To summarize, through a variety of experiences, Zamperini had developed as a teenager into one of the nation’s premier prep runners.

He participated in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. But, instead of competing in his best event — the 1500 — he switched at the Olympic trials to the 5000.

Zamperini decided to build on that experience for a return to the 1940 Olympics, slated to be hosted by Japan.

But, World War II washed those plans away in a blast of violence.

Louis joined the military and became part of a B-24 crew. The aircraft went down in the ocean, which led to 47 days of drifting in a raft in the ocean and then capture by the Japanese.

He survived incredibly harsh and brutal treatment as a POW until liberated in the wind down of the war.

Zamperini had many emotional battles to fight on the fleshy battlefield of his heart as he recovered and healed from the experience and the gnawing hatred.

He also won that war.

Lou Brissie died just a little more than a year after I had interviewed him. Louis Zamperini departed about a year after that, at age 97.

As I’ve reflected on my opportunity to interview these men — just a few weeks apart — I’ve thought of their courage, both in the fight and the rest of their lives.

Lou and Louis never sought to prove their manhood on the bloody beaches of conflict and death. It was not lust for violence but love of country and hate of tyranny that inspired their decision to throw themselves in the fight.

They wanted to open the door that made the return of freedom possible, not shut it tight. They wanted to end the death camps, not facilitate them.

Winston Churchill said: “Out of intense complexities, intense simplicities emerge.”

Lou Brissie and Louis Zamperini, two simple young men who laid everything they had on the line — even if at times in their pain death might have seemed a preferable alternative — to help put out the fire.

More:TUPATALK: Making an effort to win is not an option

This article originally appeared on Bartlesville Examiner-Enterprise: Mike Tupa: Reflecting on Lou Brissie and Louis Zamperini