TUPATALK: Rey never heard a boo he didn't like

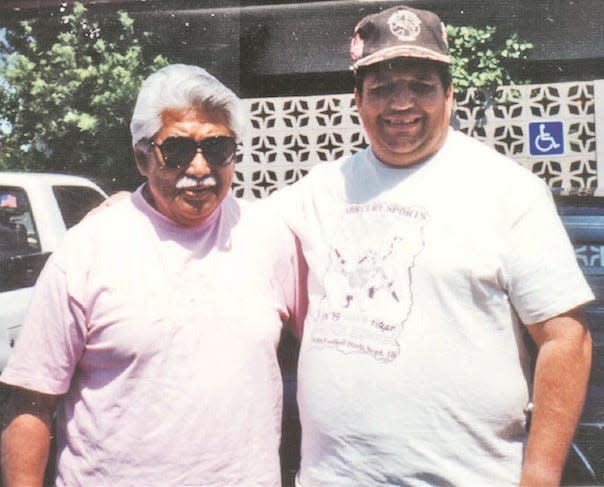

(Note: This is the continuation of my recollections of my interviews and friendship with former pro wrester Rey Urbano while he lived in well-deserved retirement in California.)

Having a woman crack his foot with the spike of her high heel — as I mentioned in my last column — was, unfortunately part of the job for Rey during his days portraying a Japanese villain in the pro wrestling ring.

He relied on a few gimmicks to get the crowd frenzied against him.

One of them was to have available a handful of sand available to throw in his opponent’s face, which earned him the nickname of the Japanese Sandman. He chuckled to me as he recalled the search the referee made prior to match to find the sand — without success. Like a spitball pitcher, Rey hid it well.

He used other props to manipulate the wrestling fans of the 1950s, for who World War II memories of the battles remained fresh.

For Rey, it was all about showmanship, an advanced form of role-playing or acting that entertained the crowds and filled the seats.

That hadn’t been his experience early in his career.

Rey began his career as a “good guy” opponent, sometimes billed with his own name, or a derivation. In Utah, for example, and probably in other places, he became known as “Kickapoo Rey” to the Native America wrestling fans. He also was known as the Filipino champion when he opened his career with a few weeks in Hawaii.

But, the money during this time was less than Rey hoped for, the exposure poor. He realized that when it came to being a star in the raucous, rugged, brutal world of pro wrestling, good guys usually did finish last in terms of spotlight.

Finally, at the suggestion of others, he considered transforming into a “bad guy.”

He chose to play a Japanese character, also at the council of someone else, because of the reaction he could arouse from the crowd. He didn’t need popularity or love by the fans to feed his ego.

He was a performer and the greater the crowd reaction the more satisfying.

Once he committed to becoming a villain, Rey experienced a new energy.

“I felt like a new man,” he told me. “I did things that Rey Urbano would never do. I was living another life. It was fantastic.”

In fact, Rey learned to love the hate by spectators.

“Listening to all the boos, I knew I was doing a good job,” he said.

Among the earlier personas he adopted were Tokyo Tom or Taro Sakuro.

He battled against the best of his era and his photo, along with accompanying articles, decorated the national wrestling magazines. Even though pro wrestling back then was organized according to geographical circuits, where a wrestler might stay six months and work in the same venues on a rotating basis until he left for another circuit, Rey developed a national following.

As I recall my experiences with Rey, I can’t help but focus on a contrast to the belligerent rascal that climbed into hundreds of different pro rings while a thunderclap of boos shook the walls.

I remember him on an afternoon in a San Jose (Calif.) hospital, where no one other than me knew who he was. To the uninformed, he must appeared just like an older man, walking each step with slightly bowed legs and pained knees.

Rey consented to drive with me to San Jose to visit a paralyzed 15-year-old young man from our town. Greg had suffered his spinal injury during a wrestling match a few months earlier.

Through my my ongoing reporting of the situation, Greg and I had become friends. I probably averaged about one trip a month for five months to San Jose — a roundtrip of about 300 miles — to visit Greg in the spinal unit treatment portion of the hospital.

Rey agreed to accompany me on one of my journeys, which I hoped would be an uplift to Greg.

We spent a long time that day on the spinal unit floor. Rey brought a smile and a true spirit of encouragement, not only for Greg but for the others fighting to adjust and live with their injury and to hopefully regain mobility, even if just the flick of a finger.

On the way home, Rey asked me to stop by a convenience store so he could check out a lottery number, I believe. His luck hadn’t come through this time.

To me, it didn’t matter.

Rey was still a winner.

This article originally appeared on Bartlesville Examiner-Enterprise: TUPATALK: Reflection of a friendship