After Turning His Back on IMSA, Ben Keating Looks for Redemption at 24 Hours of Le Mans

Ben Keating is the 49-year-old son of a car dealer, born and raised in Texas, with the easy, offhand manner of a proper Texan. He has an engineering degree from the most Texas-type school there is, Texas A&M, and shortly thereafter he went to work for his father, selling cars.

Keating was good at it. He began buying and building stores, and at 49, he has eighteen of them—whether by design or happenstance, he’s averaged one new dealership a year since he jumped into the business with both feet in 2002—with brands ranging from Mercedes-Benz to Ford to BMW to Dodge. He races like he runs his business—head down, eyes on the prize, always arriving at a situation with a plan.

But note that none of his dealerships sell Porsches. Keating likes Porsches well enough—he needs to, as that’s what he’s racing this weekend at the 24 Hours of Le Mans—but for some reason, which Keating admits he doesn’t quite understand himself, the brand just doesn’t turn him on like, say, the Dodge Viper, which he liked so well he became the world’s largest Viper dealer.

“But to get the job done, Porsche is an excellent choice,” he said, waiting for a flight last Tuesday in the Newark airport, en route to France. That’s one thing that’s different about this year’s Le Mans, moved from June to September because of the coronavirus pandemic: “Usually I spend 20 days there,” practicing, orienting, participating in the pageantry that is lacking a bit in 2020. “This year I’m only spending five.” Get there, practice, qualify, race, come home.

Speaking of Vipers, that’s what really got Keating into racing—his wife gave him a weekend at a driver’s school at the now-defunct Texas World Speedway in 2006, and he was hooked. He immediately took a Viper out of the inventory and took it to Sebring International Raceway, and for some reason they let him race. It would be nice to say he won, but he didn’t. Or even finish.

He had a lot to learn, and he did. He worked his way through the Viper Racing League and Viper Cup series, and was the national champion from 2008-2012. But as the Viper died, so did the series, so Keating turned full-time to what is now the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship, after racing in both the American Le Mans and Grand Am series before they merged.

It is safe to say Keating is addicted to racing, that he has spent millions following his passion. Not surprising, he said: He underwent counseling for addiction in high school, and it’s just his personality.

The ultimate high, then, has to be Le Mans. “I love racing the same cars, on the same track, as the best drivers in the world.” He is readily admits he is a “gentleman” driver, rated by the FIA, ACO and IMSA as Bronze, a pure amateur. (Silver is a very experienced amateur, Gold is a professional, Platinum is Fernando Alonso and his pals.) He competes in the Le Mans GTE Am class, where it is mandatory that every team have at least one amateur. The GTE Am class uses the same cars as the GTE Pro class (in IMSA, GT Le Mans cars are faster and more expensive than GT Daytona cars, which also requires an amateur driver).

He first went to Le Mans in 2015 with longtime ally Bill Riley, who ran Keating’s teams for years. He had developed some confidence after winning the GT Daytona class in the Rolex 24 Hours at Daytona, driving two cars—one won, the other came in ninth. He would drive two cars at the Mobil 1 Twelve Hours at Sebring, finishing fifth and ninth.

That first trip to Le Mans resulted in a DNF, thanks to a broken gearbox. Since then, Keating has finished the race every year, 15th in class in 2016, 20th in 2017, both in an LMP2 car. In 2018, he returned to the Le Mans GTE Am class and scored a third with a Ferrari 488 GTE. He could have won, Keating said, but he was outsmarted.

It wouldn’t happen again. Immediately the engineer in him began working out a race strategy that was, in a word, brilliant. Le Mans has such a large field that the cars pit in two groups, and since the Le Mans GTE Am class was the slowest, they always ended up in the second pack, which cost them a great deal of time and often track position.

In 2019, Keating and his co-drivers did everything they possibly could to stay in that lead pack. Usually teams put the gentleman driver in first to let him or her get the minimum number of driving time, and hope the car comes in uncrashed and maybe unlapped. Then the fast guy gets in, then the fastest guy gets in, and races for a win.

But Keating put his fastest driver, Jeroen Bleekemolen, out first, with the idea of staying in the lead pack and hoping for at least one caution. They got it. Then another. Suddenly they were two minutes ahead of the next GTE Am car. They ended up so far ahead that when Keating took his final stint, he had a massive lead.

Until the course marshals brought him in, insisting that he fix a small hole in the nose caused by hitting debris on the track. The hole had been there for hours. Then when Keating pulled out of the pits, he squealed the tires—absolutely OK in IMSA, but against the law at Le Mans. He served another penalty; the hole-in-the-nose thing was, very arguably, the first penalty, because Keating was racing the only Ford GT in private hands, and the officials were not happy that Ford was ending the GT racing program after Le Mans and the ACO had bent over backwards to let them into the series—and win. It's a conspiracy theory, yes, but it has some meat on its bones, not only with Keating's car, but the other four FOrd GTs in Le Mans GTE Pro.

When officials finally let Keating back on track, the big lead was gone. He was just five seconds ahead of one of the fastest drivers in the series. Surely he’d blast by Keating, and when they came in for fuel and a final driver change, Keating and his team would be well back in the field.

But Keating drove his remaining rules-mandated 15-minute stint, turning the fastest laps he’d ever run in any car at Le Mans, including the LMP2s. He started with a five-second lead, and 15 minutes later, came to the pits with three seconds of it left. He had kept Jorg Bergmeister, a world champion, and all the other pro drivers behind him. It was “awesome,” he said. “Magical.”

And it got more magical as Bleekemolen was the first in class to the checkered flag. Champagne bottles popped, then flowed. Keating had won Le Mans.

And then he hadn’t. He was at the airport back in Houston, in baggage claim, when the call came: They’d been disqualified. After 32 hours in post-race tech looking for something wrong, inspectors found it: The fuel tanks on all the cars are bigger than allowed, so they add chunks of foam to the tank to take up space. After 24 hours of bouncing around, the tank either expanded or the chunks shrank, because the officials said it contained about 12 ounces more fuel than was allowed. Plus, it seemed the team figured out how to refuel a split-second faster than the rules say.

Fifty-six hours after they had taken the green flag, Keating—spending his own money on the team and the car—had won, and lost, the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

“Gutted,” he said, was how he felt. But he came back, and this year, he has revised his strategy slightly. We’ll see how it works.

Keating actually races the full season in the World Endurance Championship rather than at home in IMSA, for several reasons. One is the variety of tracks—he gets to compete at Silverstone in England, Fuji in Japan, Shanghai in China. But COVID-19 juggled the schedule; Le Mans is supposed to be the last race of the season, but this year it’s in Bahrain, in November. The championship won’t be decided until then, and Keating is in third now; with double points applied at Le Mans, and a point-and-a-half awarded at Bahrain, he thinks he has a shot at a championship if he does well this weekend.

The other reason Keating prefers the WEC is how they balance the field, as opposed to IMSA. In IMSA, the Balance of Performance formula balances the performance of a make of car, not an individual team. They can speed up or slow down cars by changing wing surface area, allowing bigger or smaller tanks and faster or slower refueling times, and they can add or subtract turbo boost or the air and fuel intake area.

After roughly balancing performance that way at the start of the season, Keating says, the WEC balances performance the rest of the season by speeding up or slowing down individual cars, not the whole brand. If a particular Porsche is dominating the field, it can get “reward weight,” an ironic name for making the car heavier. If it starts losing, the weight can come off. If it continues to dominate, more weight can be added. Keating says it seems fairer to him to slow down or speed up individual cars, rather than brands.

“BoP is mostly the thing that drove me away,” Keating says, though he still competes in IMSA’s Endurance Cup, which rewards the team that does best in the four longest races—Daytona, Sebring, Watkins Glen and Petit Le Mans at Road Atlanta. Watkins was cancelled this year, and Sebring is now the last race of the IMSA season—on the same November date as the WEC finale in Bahrain. So Keating, winner of the last three Endurance Cups, won’t be able to go for four.

“I still love racing with IMSA,” he says. “But I love racing with the WEC more.”

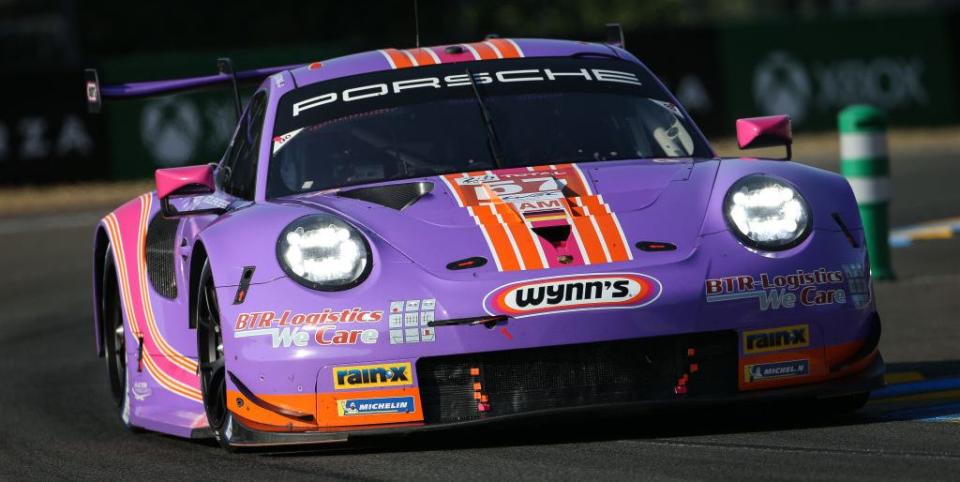

In provisional qualifying, Keating’s No. 57 Porsche 911 RSR qualified a solid eighth, far better than they qualified last year in the Ford GT. Basically, Keating says, the GTE Am class is racing the cars the GTE Pro teams raced last year.

This Porsche belongs to Team Project 1—which was awarded the victory last year – so it’s “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” situation. But Keating knows he and co-drivers Bleekemolen and Felipe Fraga can beat them – the extra fuel played no role in the Ford GT’s win – but Team Project 1 is a very well-respected group, and it should be a potent combination.

Even if he is in a Porsche. “It’s a great machine,” he says. “But I just don’t particularly need to own one.”

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos