What TV’s Norman Lear said when he shared his life story with Miami. He has died at 101

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

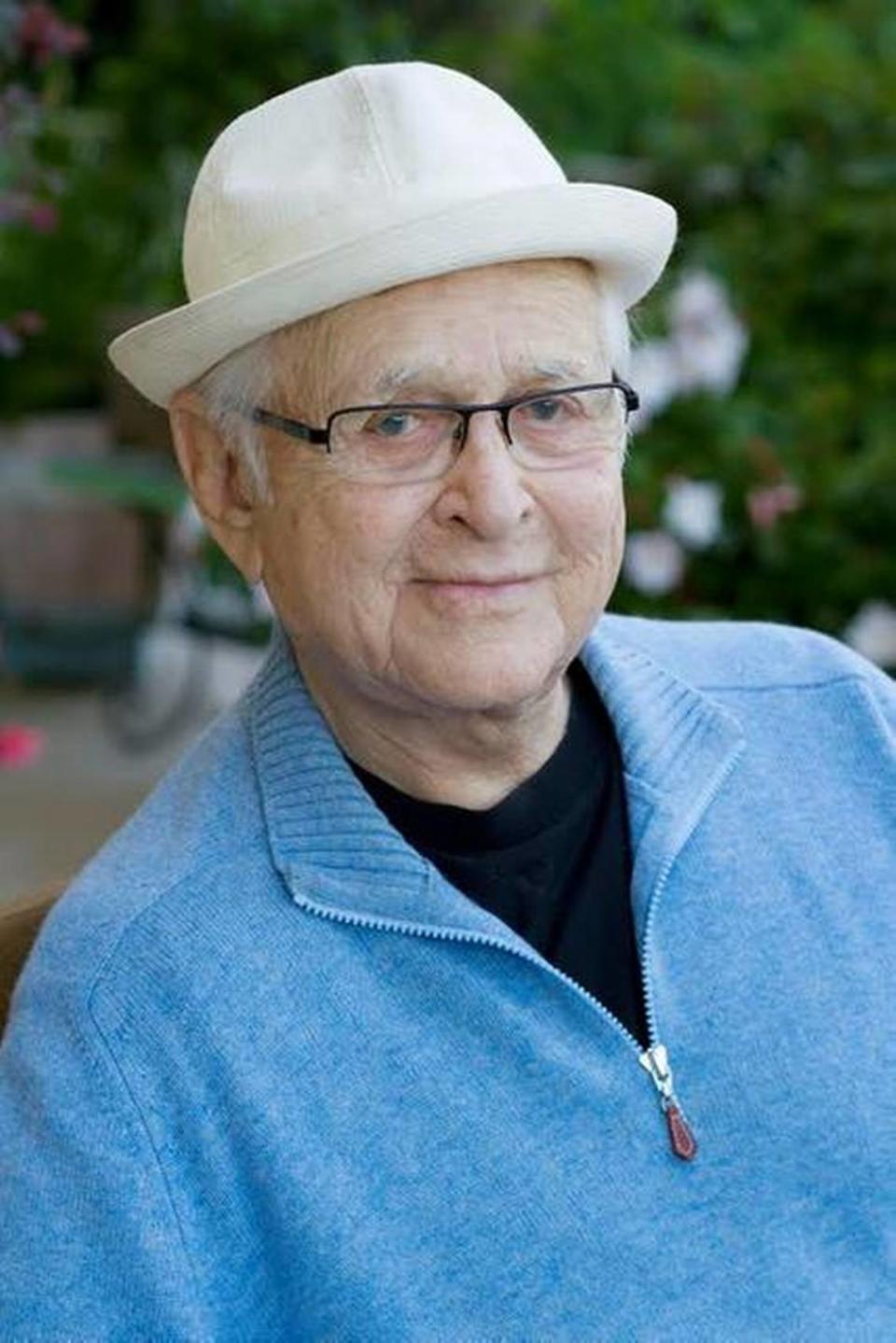

Norman Lear, the television writer and producer who pioneered placing political and social commentary into topical situation comedies like “All in the Family,” “Maude” and “Good Times” in the 1970s, died on Tuesday at his home in Los Angeles, according to the Associated Press. He was 101.

His death was confirmed by Lara Bergthold, a spokeswoman for the family.

Lear, who was still active, even after turning 100, was a political activist and still creating.

In 2017, Lear revamped his ‘70s hit “One Day at a Time,” initially for Netflix, that had been about a divorced, single mom to two teenage daughters that made a star out of Valerie Bertinelli. In the new version, Lear made the new family Cuban-American, led by Rita Moreno and Justina Machado.

That year, Lear was also made a Kennedy Center Honoree for his contributions to art and culture, alongside Miami singer-songwriter Gloria Estefan who later appeared on the retooled “One Day at a Time” and sang its updated new theme song.

In 2014, Lear published his memoir, “Even This I Get to Experience,” and promoted it with a presentation at the Miami Book Fair in downtown Miami.

To get the word out he gave a lengthy interview to the Miami Herald and spoke about how his life informed his television characters like Archie Bunker, Maude Findlay and the Meathead.

The following story, from the Miami Herald archives, ran on Nov. 21, 2014:

Norman Lear reflects

Norman Lear has been called a lot of things in his 92 years.

For his pioneering television shows in the 1970s — “All in the Family,” “Maude” and “Sanford and Son” — he was labeled “the No. 1 enemy of the American family” by religious leader Jerry Falwell and made it onto President Richard Nixon’s “Enemies List.”

Decades later, he was named a National Medal of the Arts honoree by President Bill Clinton for the same shows, as well as such groundbreaking, boundary-busting landmarks as “Good Times,” “The Jeffersons,” “One Day at a Time” and the syndicated soap opera spoof, “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.”

His father, Herman K. Lear, a charming rascal who served time in jail in 1931 for trying to sell fake bonds, once called young Norman “the laziest white kid he ever met.”

When a whip-smart Lear told his pop, whom he adored anyway, that he was putting down a whole race of people just to call his son lazy, his father retorted, “That’s not what I’m doing, and you’re also the dumbest white kid I ever met!”

Lear, who appears at Miami Book Fair International on Saturday, recounts these experiences in his new memoir, “Even This I Get to Experience” (Penguin, $32.95).

Creating Archie Bunker, Maude, George Jefferson

As a writer, Lear re-purposed such incidents from his childhood to create indelible TV characters: Archie Bunker; Maude Findlay; George Jefferson. Writing a memoir, though, was different.

“I learned that there was a great deal more to learn,” Lear said in a telephone interview. “I didn’t have my father and his influence on me in context at all — nor did I see myself as clearly when I started this as I did halfway through the writing.”

His father, portly and with a fondness for bicarb as a cure-all, is Archie. In fact, his parents, H.K. and Jeanette, met in precisely the same fashion as the fictional Archie and Edith Bunker did on “All in the Family”: in an ice cream parlor. H.K. “accidentally on purpose” dunked his hand through gobs of whipped cream and several layers of her mile-high dessert.

Lear recast his Uncle Ed as Walter Findlay, Maude’s fourth husband, who teaches his step-grandson Phillip how to urinate at 5 in the morning without waking the household. And he sees himself in Maude Findlay, that FDR-loving, liberal loudmouth who could stand up to Archie Bunker with a withering glare and an insult: “You’re fat!”

“That’s the character who shares my passion, my social concerns, and my politics,” writes Lear, who founded the liberal advocacy group People for the American Way; Business Enterprise Trust, a social vision and leadership group; and Act III Communications.

Clashing over content

“Even This I Get to Experience” covers all the lives Lear has led thus far in addition to his TV work: as a B-17 bomber crewman during World War II; a press agent and sketch writer for Jerry Lewis; father of five daughters and a son who range in age from 20 to 67; as an arts and social issues advocate.

During his TV career, Lear clashed with CBS repeatedly over content on “All in the Family” and “Maude,” which dealt frankly with race, sexuality, feminism, gun control and politics. Maude’s 49-year-old title character had an abortion in a two-part November 1972 episode two months before Roe v. Wade was decided by the United States Supreme Court.

Lear also took heat for “Good Times,” a sitcom about a black family in a Chicago housing project, and “One Day at a Time,” which depicted a single, divorced mom and her two teenage daughters in the freewheeling 1970s.

Miami professors on Lear

“Norman Lear, in terms of television history, his shows changed the whole landscape in the early ’70s,” said Mitchell Shapiro, director of the University of Miami School of Communications Honors program and professor of the special course “The Evolution and Impact of Television Content: The American Sitcom.”

“The decade of the ’60s was so politically active, but that doesn’t manifest itself in its TV shows. Those were escapist — “I Dream of Jeannie,” “Bewitched,” “Hogan’s Heroes,” “Gomer Pyle” — but Norman Lear, in 1971, with “All in the Family,” changed that,” Shapiro said.

“’All in the Family’ led to so many firsts for television and broke so much ground. It was the show that brought the ’60s into television, in effect. That was the first sitcom to touch on real-life social issues and talk about real-life political people. ... The character of Archie Bunker, there was never a character like that on TV.”

Before “All in the Family,” networks felt audiences wouldn’t accept a divorced character on a sitcom. In the 1960s NBC sitcom “Julia,” the title character, played by Diahann Carroll, was widowed, just like the Brady Bunch parents. Mary Tyler Moore, namesake character of her 1970-77 series, was supposed to be divorced, but CBS balked.

Lear’s shows upended such rules; his characters existed in a more realistic world. He introduced Maude, who was married four times, and Archie Bunker’s black neighbor George Jefferson, a reverse racist. Formerly taboo subjects were broached. Archie’s “Meathead” son-in-law suffers a bout of impotence. Wife Edith and daughter Gloria Stivic fight off would-be rapists. And, of course, Archie spouts racial epithets — and exposes racism while he does it. TV hadn’t even uttered the word “toilet” before “All in the Family,” a show on which the flushing of the family throne provided some of the biggest laughs.

Lear “was cataloging what was going on in society at the time,” said Joseph Uscinski, associate professor of political science at the University of Miami. “You see a massive sea change in the American family, and that is partially a result of the politics taking place in the ’50s and ’60s. You get to the early ’70s, and “All in the Family” and that traditional nuclear family looks like an antique.

“If you go back to the 1950s and look at “Leave It to Beaver,” there’s an episode where June and Ward had to decide if they’d let the Beav hang with the son of a divorced woman. By the ’70s and ’80s, if you wouldn’t let your kid hang with a divorced family friend, you wouldn’t have many friends.”

Changing times

Lear says now he could probably never get “All in the Family” on the air today.

“I know most of the people running shows, and they tell me it wouldn’t happen today, that ‘All in the Family’ wouldn’t get on the air today any more easily than the two to three years it took me to get it on in its time. They tell me a lot of the subjects they can’t do,” Lear said. “We are too politically correct, which is another way in my mind of saying we’ve lost the ability to kid ourselves. We’ve lost the ability to laugh at ourselves.”

The memoir was a 20-year project, Lear said, conceived soon after the cancellation of his NBC sitcom, “The Powers That Be,” a Washington political satire. In the interim, Lear bought, and toured the country with, an original copy of the Declaration of Independence. He also serves as a chairman emeritus of the Concord Music Group, an independent jazz and pop boutique label and publishing arm for artists including Paul Simon, Paul McCartney and Kristin Chenoweth.

Writing his memoir

Actual writing time of the book, once his staff combed his files, took about six years, Lear said. “I’m getting the biggest kick that people are reading it.”

When Lear finished writing “Even This I Get to Experience” — which also deals in his customary unflinching way with family dramas that included a difficult relationship with his mother, costly divorces and career setbacks — he came upon a realization: He has been “learning how hard it has been to be a human being.

“I don’t care about the circumstances of birth, and most everyone has it far worse than I had, but it’s not easy whoever the hell you are,” he said. “There is the horizontal journey and the vertical journey into oneself is, I think, the most rewarding and endless. We have no word, no idea, what is ‘next,’ if there is a ‘next.’ That is one of the most attractive things about being alive — that wonderful mystery at the end.”