WHO-TV's Erin Kiernan revealed her son's autism diagnosis on air. Now, she works to open minds

Why aren’t you doing stories on this?

The question haunted Erin Kiernan as she drove away from her morning shoot.

She’d just finished an interview with two former CBS producers who were in town to screen their film, “In a Different Key,” which tells the story of the first person diagnosed with autism. Back in the 1990s, one of the producer’s kids received an autism diagnosis and, like a good reporter, she set out to learn everything she could about a spectrum still in its infancy. Her research turned into a series of reports that were among the first to put names and faces to autism, helping to shape an emerging field of medicine.

While they filmed b-roll, Kiernan confided that her son, Michael Francis, had recently received an autism diagnosis. She and her husband were still reeling, figuring out a way forward in their new lives, and Kiernan, too, had turned to research to salve the fear that sat like a weight on her chest.

So, the producer said: Why aren’t you doing stories on this?

She and her husband, Michael, had kept the news close, just family and dear friends. She could report autism stories without divulging her own, of course, but that would be disingenuous — especially for someone who regularly asks others to share the deepest parts of themselves.

“We were in the midst of this thing, with this learning curve that felt so incredibly steep to me,” she says. “I knew so many other people were dealing with it, too. And so many other people had no idea about it, or what it was, or what it looked like.”

So when the producer asked her that question, Kiernan felt compelled, almost “called into duty to start educating,” she says.

Her resulting, brutally honest series, “Understanding Autism,” which opened with a nearly 10-minute story about her family’s journey to a diagnosis and beyond, airs “every Thursday night forever,” she says with a laugh.

For about a year, Kiernan stewed on whether to open up about her son’s disorder, she says. A main anchor in a local market where that’s the same as being a celebrity, she knows more than most the oppressive heat of the public glare that comes from broadcasting personal traumas.

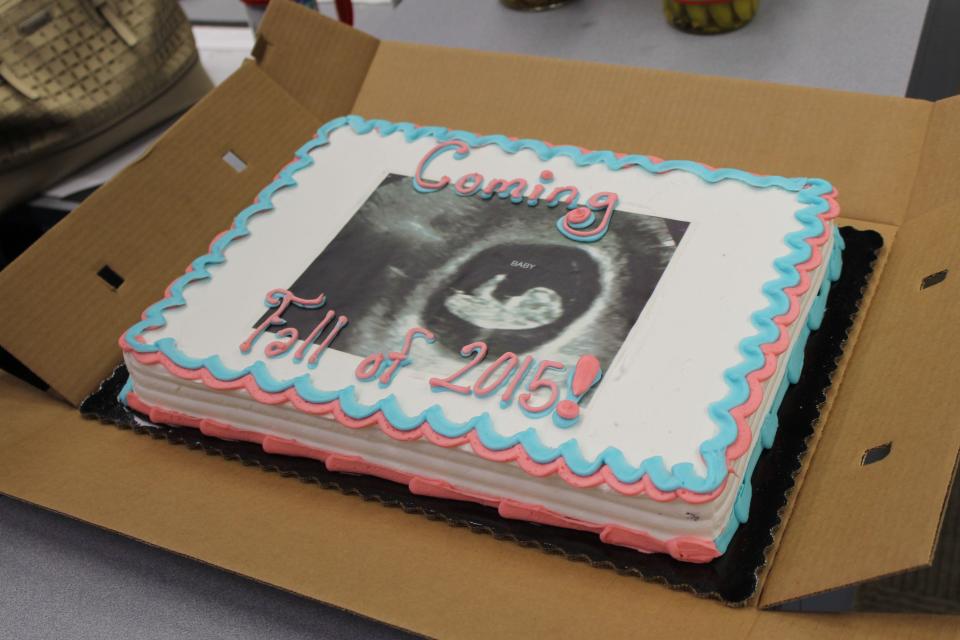

Nearly 20 years ago, she revealed that she became pregnant at 16 and found an adoptive family for her son, David. And she allowed herself to be vulnerable on camera again in 2015, when she discussed her decadelong infertility struggle.

In each iteration, including this most recent one, she’s been reminded of the immense power of empathy. To her, when the chances viewers could be nasty are measured against even just one mother feeling less alone, there’s simply no other choice but to lift her voice.

“People are carrying around these burdens and feeling like they can't tell anybody or nobody would understand or no one would care,” she says.

“It just sort of cracks your heart open.”

‘Denial is an interesting thing’: Diagnosing autism

Kiernan and her husband tried for a decade to have a child; a journey filled with particularly sharp pains considering she had already given birth once — just not at the right time.

"I was really, really angry and bitter at this point," she said in 2015, when she went public with her infertility struggle. "Like, are you serious? I get pregnant when I don't want to, and I try to make a good decision in a bad circumstance and now, now, I can't have children.”

"I was screaming at God, 'How can you do this to me?'"

So when, after four rounds of in vitro fertilization and one failed adoption, Michael Francis, now 7, made his much-anticipated debut, the new parents were “completely goo-goo ga-ga over this baby,” she says.

In his earliest stages of development, Michael Francis was hitting all the important milestones: He looked at people when they were speaking, pointed at things, followed stories and mimicked the words in his favorite books.

But as he grew into a toddler, he began staring off into the distance, not reacting to shouts of his name, and falling into repetitive behavior loops. And when his sister, Audrey, was born, he started having tantrums and exhibiting lots of aggression.

Eventually, he just stopped talking.

“That's when I had that little, ‘Something’s not right,’ in the back of my head. But I didn't want something to not be right,” she said, pausing.

“Denial is an interesting thing. I mean, you just don't want anything to be wrong with your kid.”

At first doctors told her that Michael Francis’ behavior was normal. He’s just upset about the baby, they said. And the Kiernans clung to that hope.

But in the quiet moments, she found herself screaming at God — again.

And the fear sat like a weight on her chest, just as it had when she was a teenager and again as she trudged from doctor's office to doctor's office for fertility treatment, wearing hope like a shield, lest her heart take one more beating. At the worst of times — when she wasn’t sleeping and the scale seesawed — she lived in a state of hyperventilation, each breath shallower and shallower.

“It's dredged up a lot of the same sort of feelings I felt after giving up David and going through infertility, like loss that's just visceral,” she says. “It has that physical element to it, and it’s kind of debilitating.”

A few weeks into his first year of preschool, Michael Francis’ teachers suggested the Kiernans schedule an assessment with their Area Education Agency, a state-run group that identifies kids with special needs and helps create safe learning environments.

The women working for the AEA — therapists and psychologists and former teachers — marshaled resources and answered questions.

They aren’t qualified to give a diagnosis, but they had seen enough to tell Kiernan it was time to see an autism specialist.

Keeping pace: More people on the spectrum; same number of doctors

A new patient’s parents often emanate a swirl of unease and confusion and a twinge of terror when they meet with Dr. Nate Noble, one of the state’s most respected developmental-behavioral pediatricians. But more powerful than all that darkness is the parents' palpable relief, he says, because they know they’re finally going to get answers — ones they’ve probably been seeking for years.

“It’s validating people's concerns. It’s being able to say to a first-time parent, ‘You were right the whole time.’ And not only were you right, but this is not your fault,” he says. So “Can I excise from you that needless, senseless, worthless guilt? I noticed you brought it in. Can I just put it here? I'll keep it. Because you aren’t powerful enough to have caused this problem.”

He understands the power of shared experience well and welcomes the comfort that comes from a respected community member like Kiernan using her voice, letting people feel like she’s finishing their sentences.

“I think it’s an important message that neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism are not respecters of people or place or position,” he says. “You can be on TV or be the president of the United States or be the guy who helps keep the lights on here. You're still up against the same battles.”

He hopes stories like Kiernan’s can lead to tangible increases in support, training and interventions, especially in regard to creating spaces that keep tweens and teens needing the highest levels of care out of emergency rooms and psychiatric wards.

Since UnityPoint opened Noble’s clinic a decade ago, the criteria to diagnose Autism Spectrum Disorder — a broad range of conditions that affect communication, behavior and social skills — hasn’t changed drastically, but the number of individuals identifying characteristics within themselves and seeking opinions and interventions has ballooned.

With more individuals falling on the spectrum — joining nearly 20 percent of metro kids who have a neurodevelopmental disorder and one in 36 having autism — “it becomes difficult to see how we're going to keep pace with this problem.”

“There are less than 800 developmental-behavioral pediatricians in the United States, and 20% of that workforce is over the age of 60,” he says.

And the specialization is a hard sell for new doctors who have focused their entire training on fixing and curing.

“I fix perspectives. I fix outlooks. I speak life and truth into families,” he says. “We make some things better with medications or therapies and services and skill sets and celebrations. But at the end of the day, those bones are not going to be fixed by me.”

While there will always be a need for more providers and more services, Noble says it’s “myopic” to think more is the only answer to address wait times and availability. Instead, he says, providers already working in the state need to be equipped to handle certain cases.

“Train people locally; that is the only way forward. Teach the primary care provider, the pediatrician, the internal medicine physician, how to address these issues in their own clinics with the time, energy, resources that they have,” he says. “I am not shy about giving my cellphone number to people because I would rather do that and see you help somebody in your clinic right now than say, ‘Let’s just refer to Noble and see what happens.’”

“Iowa is a state where whatever you plant in the ground grows,” he adds. “If we don't have it, it's because we don't have enough guts to plant it.”

Moving forward: ‘Every day is hard. But every day is also hilarious’

In the four years since Michael Francis’ diagnosis, the Kiernans have learned to celebrate every small breakthrough. The “tiniest of things,” she says by way of emphasis.

That time an episode of “Blippi” got Michael Francis interested in grapes, for example, and he actually ate one. That breakthrough definitely went in the gratitude journal, she says.

Or when he speaks in a complete sentence: I want to go to McDonald's and have a cheeseburger.

“This is hard, hard, hard; every day is hard,” she says. “But every day is also hilarious and filled with the sorts of things that other families don't think of celebrating. We get notes home from his special-education teacher every day, and there's always something that's like, ‘Oh, my God, that's awesome.’”

Kiernan can see how Michael Francis’ diagnosis is molding and shaping her daughter, Audrey, 5, into a defender and advocate for not only her brother, but all kids who are different. And she herself has felt exponential growth in her own capacity to love.

“This has so radically changed our perspectives and our outlook on life, and the empathy with which we approach all people,” she says.

The list of what she doesn’t know about autism is long and, with scholarship evolving regularly, she’ll probably always have a lot to learn. Someone once told her that, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.”

“I could literally do this series forever, and every single story would be radically different,” she says.

Since being called to educate on autism, Kiernan’s series has covered new and sometimes controversial therapies; one family’s heartbreaking decision to put their child in a group home; and a teacher’s small kindness that brought big smiles to her special-education students.

And after each report, her inbox fills and her social media alerts buzz, a kind of audible affirmation she was right to lift her voice and share her family’s story.

“That validation of sharing your story is that it's meaningful to other people and to helping them cope,” she says. “That's why I wanted to be a reporter. I wanted to change things.”

Even if sometimes that change just means cracking a few hearts wide open.

COURTNEY CROWDER, the Register's Iowa Columnist, traverses the state's 99 counties telling Iowans' stories. You can reach her at (515) 284-8360 or ccrowder@dmreg.com. Follow her on Twitter @courtneycare.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Why WHO-TV's Erin Kiernan revealed her son's autism diagnosis on air