Twice, car-carrying ships have burned en route to RI. Fire officials say they're prepared

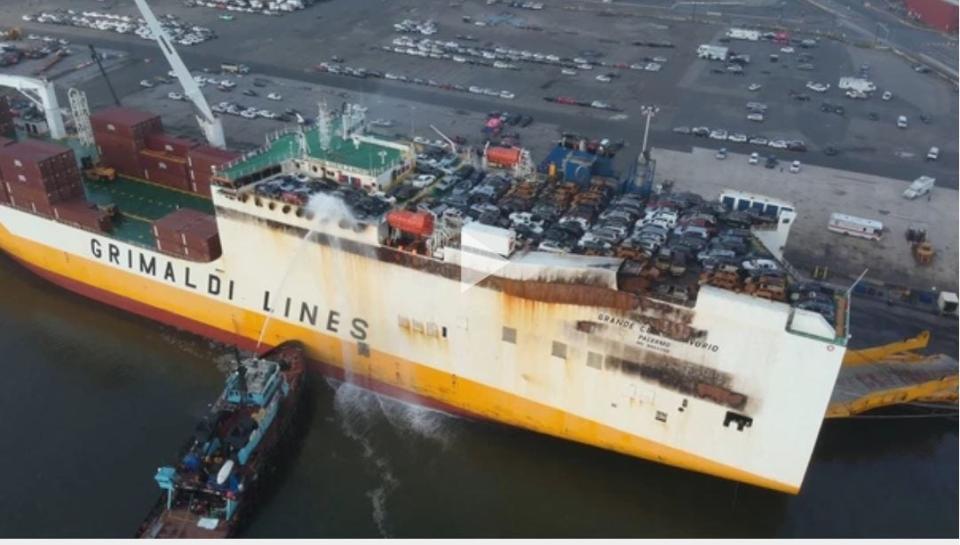

The Grande Costa d'Avorio, a mammoth car-carrying ship, was expected in Providence soon after its stop in Newark in July.

In Rhode Island, port workers would load even more used cars and trucks onto the ship. Then the Grande Costa would float the vehicles across the Atlantic Ocean to Africa, where people needed them.

But the Providence port call never took place: Instead, an intense fire broke out aboard the Grande Costa, killing two New Jersey firefighters and burning for six days.

The second time a car-carrying ship bound for Rhode Island was destroyed by fire

It was the second time in less than 17 months that a raging fire had played into the destiny of a car-carrying ship expected in Rhode Island.

In February 2022, a blaze had overtaken the North Kingstown-bound Felicity Ace, which later sank about 220 nautical miles off the Azores, according to the ship's operators.

The second disaster, aboard the Grande Costa, raised the significance of some obvious questions about the risks of car-carrying ships in Narragansett Bay.

Recent interviews with Providence fire officials and the operator of ProvPort show that local oversight by the U.S. Coast Guard has picked up following the Newark fire, and that has fostered recent meetings, inspections and enhanced coordination.

Providence firefighters plan to work in conjunction with Coast Guard

"The Coast Guard is well aware of the risk for these ro-ro ships," said Providence Deputy Assistant Fire Chief Craig Grantham, referring to the ships' nickname, which is short for roll-on, roll-off. "That's one of the reasons they've been … reaching out to us to see how we are handling it and the kind of risks that we have to deal with on our side."

After taking some tours of ships to increase their familiarity, Providence firefighters are working with the Coast Guard on some additional training, according to Grantham. Another task that's in process involves procurement of spare equipment for connecting water lines to certain foreign ships, he added.

"Nobody wants a ship to burn up anywhere," Grantham said.

In interviews, Providence fire officials including Chief Derek Silva, and Christopher Waterson, who is general manager of the company that operates ProvPort, both emphasized that the Coast Guard regulates safety and fire prevention aboard car-carrying ships.

But they also expressed confidence in the particular aspects of safety and fire prevention they are responsible for when car carriers visit Providence.

Silva and Grantham say Providence firefighters will board a burning car carrier only to save lives. Otherwise, local firefighters intend to battle any shipboard fire from shore and from fire boats.

What is the history of car exporting in Providence?

Waterson's company started managing operations at ProvPort in 2007.

As part of that, the company also manages unionized workers who load and unload ships. The port has eight full-time workers and typically employs 60 to 80 workers, all members of the International Longshoreman's Association, on a temporary basis, Waterson says.

The port operation has been involved with loading outbound car-carrying ships since about 2008, Waterson says.

These days, ProvPort loads roughly one to two ships per month, which amounts to about 1,000 vehicles, Waterson says.

In the past, the operation has loaded as many as 3,000 vehicles a month, Waterson says.

He recalls an occasion several years ago involving a fire that affected 30 vehicles.

A report obtained from the Fire Department describes a fire within a 10,000-square-foot storage facility on Fields Point Drive, far from where carrier ships are loaded.

It details how sparks from metal parts on the wheel of a forklift made contact with a spill of some flammable fluid used in automobiles.

At the time, the forklift was moving the vehicle to a location for recycling and battery removal, the report says. The resulting fire, it says, destroyed 28 vehicles.

For many years now, loading operations at the ProvPort terminal have taken special precautions to avoid such mishaps near the ships or on their decks, Waterson said.

For example, he said, battery cables are disconnected from car batteries and taped to eliminate the chance of sparks.

Many of the cars leaving Providence are not in drivable condition on U.S. roads, according to local fire officials.

Rolling them through a yard – or pushing them up ramps, sometimes multiple ramps, and onto a cargo deck – can create friction, heat and then combustion.

"The chances of something overheating due to friction because of previous damage on the car is greater," Grantham said.

For these reasons, said Waterson, the port's policies limit the distances that vehicles can be rolled onto the ship under certain conditions.

The typical ships have entrances on the fifth or sixth deck and the port's policy does not allow non-functioning vehicles to be pushed higher than the seventh deck, Waterson said. Some other vehicles are brought onto the ship via forklift, which eliminates rolling.

What we know about the fire aboard Grande Costa in Newark

In September, Grimaldi, an Italian company that owns the Grande Costa and frequently ships vehicles out of Providence, blamed the Newark fire on workers who loaded the ship.

In a federal court filing, the company asserted that the ship's loaders moved a "non-running" Toyota Venza from a terminal to the Grande Costa's 10th deck.

A loader pushed the Toyota with a Jeep Wrangler, which started a fire on the underside of the Jeep, says the filing.

Coast Guard investigators have not posted any findings regarding the cause of the fire on the Guard's website. An attempt to seek comment from the Guard was not successful earlier this week.

The New York Times reported that firefighters who went to the ship's berth found that their own standard, 2.5-inch hose lines would not connect to the smaller one-inch hoses on the European-built ship.

"Less water, less volume, less penetration and less protection for the guys," a firefighters' union president told The Times.

Two firefighters issued mayday calls from within the ship.

Both died. One of them was found pinned between two flaming vehicles, according to The Times.

Providence Fire Assistant Chief Stephen T. Houle emphasizes that conditions on a loaded car-carrier ship are quite different from what passengers see on the car decks of the Block Island Ferry.

"It's extremely congested front to back – trunk to trunk, hood to hood," Houle said.

"There are walkways, which are very, very limited," he said. "From the presentation we got from the Coast Guard a few weeks ago, it's a very high-hazard, high-risk area to be operating in zero visibility."

What was the Coast Guard's reaction to the Grande Costa fire?

In July, soon after the fire aboard the Grande Costa in New Jersey, the Coast Guard made contact with ProvPort, Waterson said.

The federal agency performed a fresh assessment of the local shipping operation's compliance with fire safety requirements, from fire extinguishers to the training of personnel in fire response, Waterson says, adding that the operation passed muster.

"We go above and beyond … what is required to make sure that it's a safe operation," said Waterson.

He added: "We don't … look at things that happen elsewhere and say, 'That can't happen to us,'" he said. "We look at it and learn to improve."

Waterson said he was encouraged earlier this fall by a meeting between his company, the Coast Guard and the Fire Department, acknowledging that the shipping industry seems to be "in a bad run from these things."

"That's really how the Coast Guard characterized it," he said.

"There have been ship fires throughout time on this type of ship and on other types of ships," added Waterson, who acknowledges four or five such major incidents over the last four or five years.

"That's not to say there's any more or less of a risk than there ever was," he said. "It's just that there happens to be a stretch of bad luck, if you want to call it that."

In May 2022, Lloyd's List cataloged six incidents resulting in the "total loss" of ro-ro ships over a span of five years.

How would Providence firefighters handle a ro-ro fire?

The command staff of the Providence Fire Department have talked over their strategy for dealing with a flaming ro-ro ship, Silva said.

If necessary, he said, they will lean on a local task force of fire boats. Providence, East Providence, Warwick and Cranston all have fire boats with the same capabilities staffed by firefighters with the same training, he said.

"We would try to extinguish it, but not from onboard the ship," Silva said. Firefighters could board in a rescue situation, he said.

"If it was one car going on that ship and everyone's off it," said Silva, "we would still probably not get on top of that ship."

Both Grantham and Silva emphasized that ro-ro ships are supposed to have on-board fire suppression systems. Some systems will seal up an area of a ship, remove oxygen and inject carbon dioxide.

Part of the job would involve monitoring the ship's waterline as water is poured onto it and then making appropriate adjustments if the ship is sinking too low or at risk of capsizing in the port, they said.

"There's a lot of tactical stuff that can go on," Grantham said. "What we don't want to do is just pretend it's a house fire and put people into the ship like it's a house fire."

Silva emphasized that while Providence firefighters have done some reviews and discussed their plans, they have not made any major changes based on the carrier fires.

The city's firefighters have been prepared for the worst-case ship fires at the port, and they remain prepared, he said. "To be honest with you," Silva said, "a car-carrier ship catching on fire does not keep me up at night."

Silva mentions that batteries for electric vehicles have become a source of worry for firefighters all over the world.

Investigators delving into the 2022 demise of Rhode Island-bound Felicity Ace devoted some attention to the role, if any, of lithium-ion car batteries in electric vehicles on the ship, according to Lloyds.

Silva is less concerned with the fire risk aboard 10-deck ships in port and more concerned with hazards inside three-deck houses. Firefighters spend a lot more time dealing with emergencies in those residential settings where, under the law, fire inspections take place with far less frequency, limited to the checking of smoke detectors when a house is sold, he said.

Here, too, though, batteries for small electric vehicles are a concern: Silva said he pictures a college student buying a scooter on Amazon and charging it improperly and dangerously in the living room every night.

"Those are the things that worry me," he said.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Fire officials consider risks of car-carrying ships docking at ProvPort