Two Case-Shattering Clues Point to the Real Name—and Face—of Jack the Ripper

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

This story is a collaboration with PopularMechanics.com.

The legendary mystery of Jack the Ripper’s true identity, an enigma that has endured for over a century, might be coming to an end thanks to the re-emergence of an old memento and a new theory proposed by a former police volunteer.

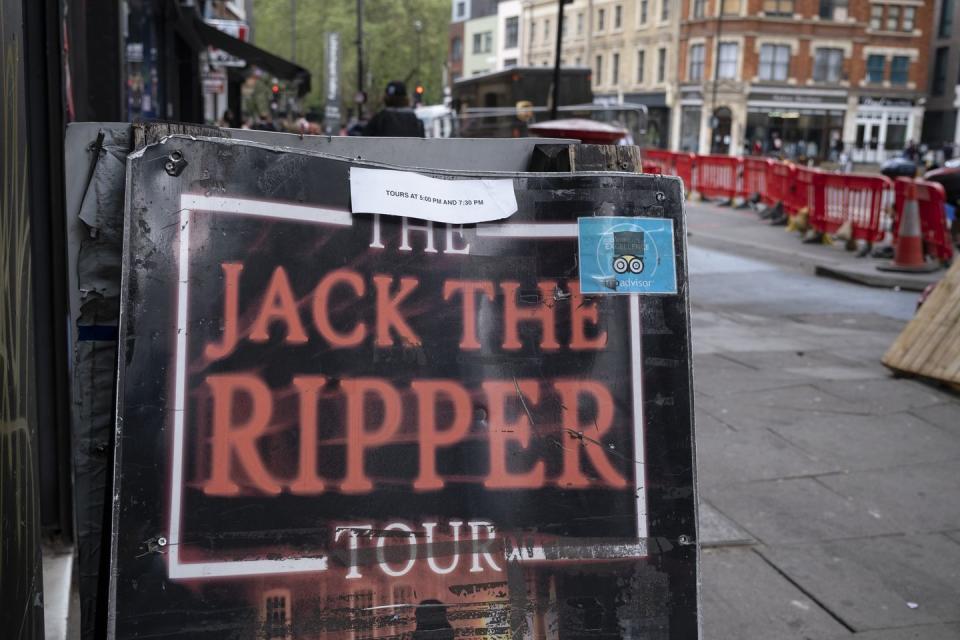

Are true crime obsessives headed down yet another tantalizing shrouded alley, only to find a dead end? Or will there finally be a proper face put to the notorious name that, once whispered in fear, is now shouted by endless tour guides in the Whitechapel district of London?

Perhaps the most famous cold case in history, the mystery of Jack the Ripper’s real name has attracted more sleuths, professional and amateur, than any other case of the last 130 years. That the identity of the killer has remained unknown all this time has allowed him to slip into the realm of the morbidly fantastical, like the fictional occupants of penny dreadful novels such as Sweeney Todd and Springheel Jack.

Jack the Ripper has inspired films, novels, operas, and video games. He’s even tousled with Batman on the illustrated page. After all, innumerable theories abound as to the identity of London’s most infamous killer, and since we’ve long been left wondering who he was—or what he even looked like—we’ve let our minds imagine anyone, real or fake, wandering the foggy streets of Whitechapel.

But now, we might actually be close to answering the impossible question: Just who was Jack the Ripper?

What Are the New Clues That Reveal Jack the Ripper’s Identity?

A newly rediscovered artifact that once belonged to Frederick Abberline, a detective who investigated Jack the Ripper back in 1888, is the first intriguing development.

As the New York Post reports, a custom-engraved walking stick that Abberline owned had long been held within the Police College in Bramshill, Hampshire, but it “...was feared lost when the institution was shut down in 2015.”

However, the cane recently reappeared when staff members at the College of Policing’s headquarters Ryton were “searching through memorabilia.” The cane itself, in addition to being photographed and posted online, is now on display at the College of Policing “to highlight advancements in police technology to recruits.”

This walking stick is significant because Abberline had carved into the cane the only existing composite image ever made of Jack the Ripper, based on witness testimony. While the cane alone doesn’t tell us who the infamous killer really was, its rediscovery does allow us to put a face to the Jack the Ripper.

A single cane from the 1800s might not close the case by itself, but a former police volunteer believes that combining the same kind of witness testimonies that led to that composite image with a close examination of medical records of the era could lead to a suspect long overlooked in the investigation.

As noted in The Independent, Sarah Bax Horton, the grandchild of an investigator who worked on the Jack the Ripper case, believes she has found the man responsible for the grisly Whitechapel murders.

Through examining medical records of the era, Horton says she has identified cigar maker Hyam Hyams as the real man behind Jack the Ripper. While Hyams’ profession likely means he was proficient with a knife, the weapon used in the Jack the Ripper killings, Horton’s theory relies more on the maladies that afflicted Hyams, both mental and physical, which align with what we know about Jack the Ripper.

“For the first time in history, Jack the Ripper can be identified as Hyam Hyams using distinctive physical characteristics,” Horton told The Telegraph regarding her theory. Reviewing medical notes for Hyams, Horton found that he had “an irregular gait and an inability to straighten his knees, with asymmetric foot-dragging.” Eyewitnesses in the Jack the Ripper investigation noted that the infamous killer also had an irregular gait.

Horton also notes that Hyams had a documented history of mental illness and violent outbursts. The Independent notes that Hyams “...repeatedly assaulted his wife, fearing she was cheating on him, and was eventually arrested after attacking her and his mother with a ‘chopper’.” Records of Hyams from across a number of infirmaries and asylums indicate that “his mental and physical decline coincided with the Ripper’s killing period, escalating between his breaking his left arm in February 1888 and his permanent committal in September 1889.”

Of course, this triangulation of medical records and century-old eyewitness reports is unlikely to be enough to get most self-described “Ripperologists” to declare “case closed.” But one has to wonder: At this point, what would be enough?

Is it possible that there could ever be a satisfying conclusion to the world’s most famous cold case? And why does it continue to captivate true crime enthusiasts all these decades later?

Was Jack the Ripper the First Serial Killer?

Jack the Ripper, a moniker adopted for the unidentified murderer, was not by any means the world’s first “serial killer.” History, unsurprisingly, is littered with figures who would fit that bill depending on how specific a definition you choose.

Liu Pengli, the Prince of Jidong in the 2nd century B.C., slaughtered over 100 civilians. Dame Alice Kyteler, the “Witch of Kilkenny,” poisoned four of her husbands in 1300s Ireland. Joan of Arc’s comrade-in-arms Gilles de Rais confessed to the killing of over 100 children. Countess Elizabeth Báthory’s alleged killings of servant girls had already become the stuff of macabre folklore by the time the Whitechapel murders began. And there are countless figures in history who could be rightly categorized as serial killers, despite their victims being viewed as “property” or “subhuman” by the ruling governments of the time.

But while Jack the Ripper wasn’t the first serial killer, he was the first to become a media sensation and the subject of fascination on a global scale. He might not have been the first serial killer by the literal definition, but in the manner in which we view the macabre topic, the exploits of the unknown man behind the moniker set the template for more than a century of morbid speculation and fascination.

Who Did Jack the Ripper Kill?

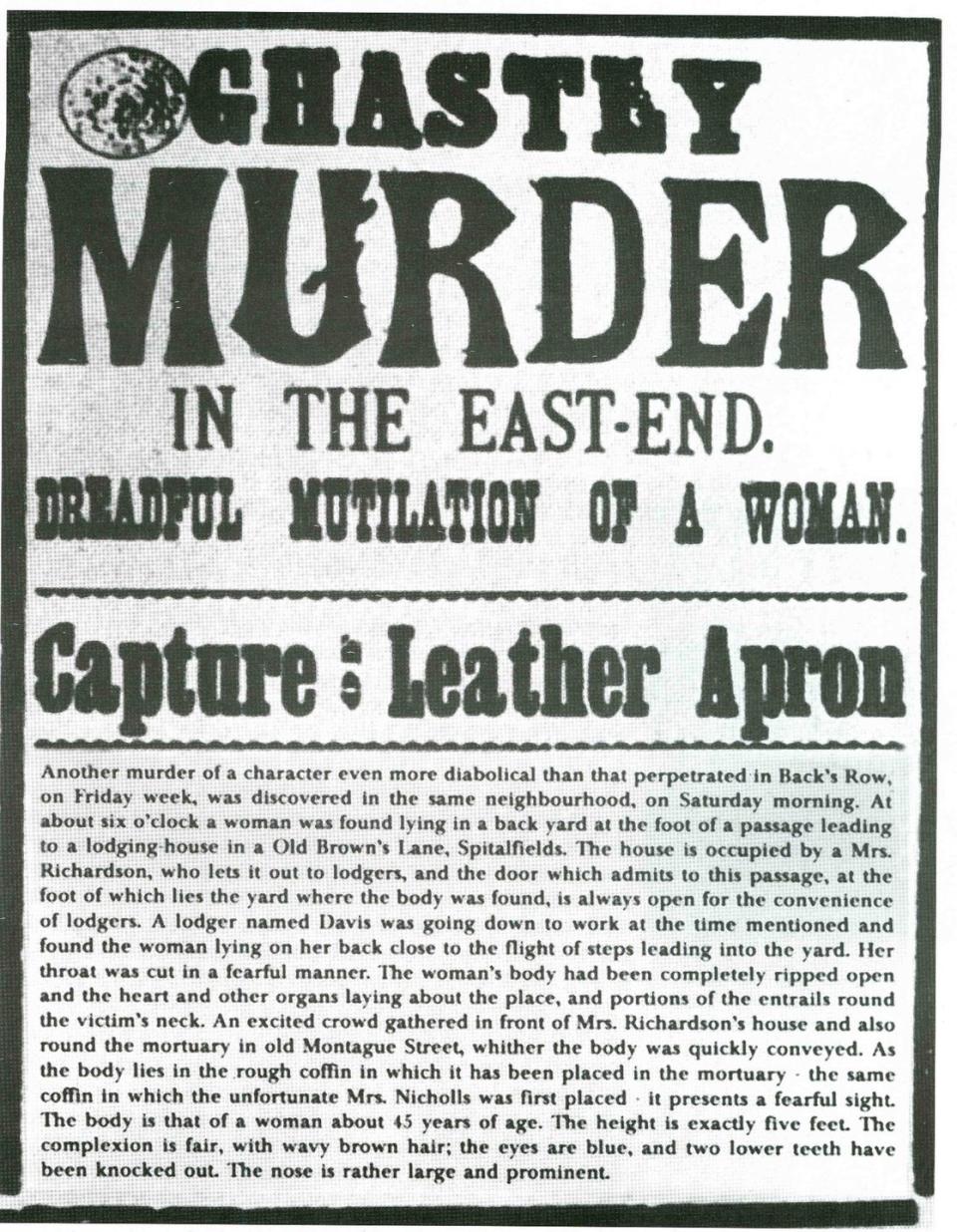

There are five “canonical” murders attributed to Jack the Ripper: those of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. (Of course, as is the case even today in cold case investigations, there are other killings that are, at times, theorized as also being at the hands of the same murderer.) Biography.com’s previous reporting notes that these murders all took place from August 7 to September 10, 1888, all within one mile of each other, and all targeting women of the same profession: sex workers.

As we previously pointed out, typically “the death or murder of a working girl was rarely reported in the press or discussed within polite society.” One might think that the “sadistic butchery” of the Jack the Ripper killings might have pushed their discussions further to the fringes of societal conversation, rather than to the center of public fascination. Instead, the newly affordable mass media of the time allowed the Jack the Ripper saga, including a series of mocking letters the killer reportedly sent to Scotland Yard, to serve as a macabre mirror to a society that had been otherwise priding itself on its progress and achievement.

What Was Jack the Ripper’s London Like?

The 19th century, at least in the eyes of high society, saw the United Kingdom launch itself into modernity. The era of Queen Victoria saw England’s streets becoming bathed in gaslight, the skyline filled with smokestacks from the Industrial Revolution. It was Isambard Kingdom Brunel connecting the nation through the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western Railway, and the SS Great Briton, amongst others. To stand in some parts of London by the latter decades of the 19th century must have felt as though one had stepped into the future, with wonders and marvels of modernity accessible to the many rather than simply the few. This was the side of London that Great Britain wanted the world to know about.

But of course, London is a big city. And the bright lights shone on some parts also cast shadows on all the rest. Such is the case in Whitechapel and its surrounding areas, where Jack the Ripper stalked his prey.

Consider this scene based on Biography.com’s earlier reporting:

“In the late 1800s, London’s East End was a place that was viewed by citizens with either compassion or utter contempt. Despite being an area where skilled immigrants, mainly Jews and Russians, came to start a new life and start businesses, the district was notorious for squalor, violence, and crime. Prostitution was only illegal if the practice caused a public disturbance, and thousands of brothels and low-rent lodging houses provided sexual services during the late 19th century.”

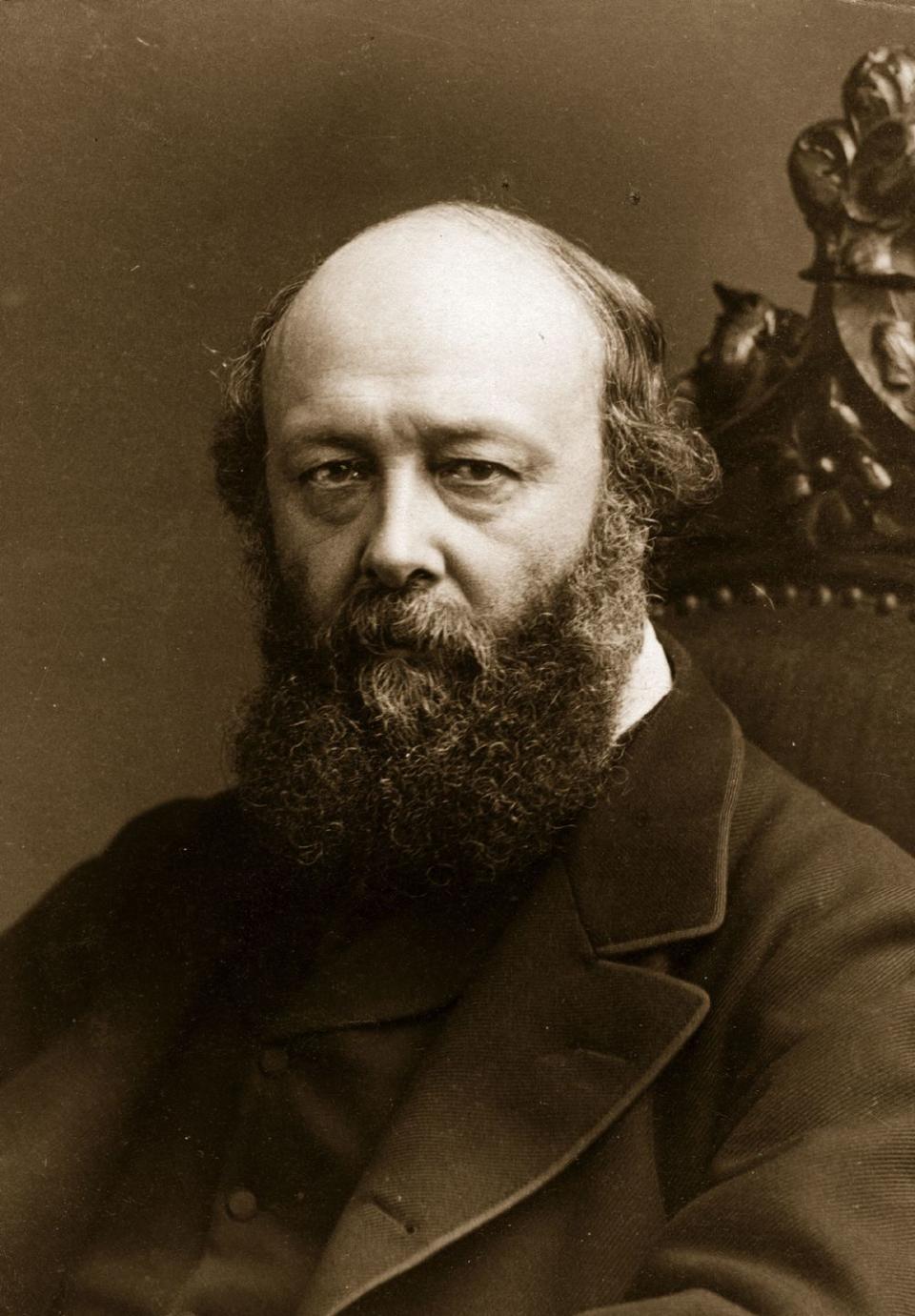

In Victorian Parliament’s push for progress, poverty became a consequence. This industrial projects displaced a large number of people, such that even Conservative Party members were demanding social reform to repair the damage done. “Laissez-faire is an admirable doctrine,” Conservative Party leader Lord Salisbury said in an 1883 National Review article entitled “Labourers’ and Artisans’ Dwellings,” “but it must be applied on both sides.”

Much was made of the squalor in which the poor and working class were living while the wealthy in London lavished in the height of modernity. Parliament passed The Housing of the Working Classes Act 1885, which allowed them to condemn buildings they deemed slums. But this was merely a cosmetic action; the 1885 act didn’t allow for the government to create any new residences for the now-displaced people within them.

How Did Jack the Ripper Change the World?

The Jack the Ripper murders served as a wake-up call for Great Britain and the world, as the details of these grisly, monstrous crimes were contrasted against the supposedly advanced society that had inadvertently created the circumstances that had allowed them to fester.

The same forces and actions that allowed for the creation of the London Underground also created the seedy London underbelly that fed victims to craven creatures like Jack the Ripper. In much the same way the Manson murders in America 80 years later would be contrasted against the optimistic “Flower Power” movement of its era, Jack the Ripper forced the public to reconcile with the consequences of the steam-powered era of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and wonder if this utopian vision wasn’t terribly unstable as well.

The mystery of Jack the Ripper casts a long shadow over London to this day. Clearly, amateur sleuths still puzzle over the identity of the man who wielded a knife on the streets of London and claimed the lives of innocent women struggling to get by. But the most significant consequence of the killings isn’t a century of true crime speculations, nor the many books, films, and walking tours it inspired.

The reporting in the press on the Jack the Ripper killings led to a public outcry amongst the populace for social reforms to protect the most vulnerable. Reacting to the outcry, Parliament passed, amongst other acts, the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890, which now gave them the ability to purchase land and build new housing for those displaced by the condemning of buildings deemed to be in poor condition.

In a bit of pithy commentary, playwright George Bernard Shaw declared in The Star that Jack the Ripper had, in his brutality, led to more social change than any academic or activist of the era:

“Now all is changed. Private enterprise has succeeded where Socialism failed. Whilst we conventional Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation, and organisation, some independent genius has taken the matter in hand, and by simply murdering and disembowelling four women, converted the proprietary press to an inept sort of communism.”

Why Are We Still Searching for Jack the Ripper?

Like Sarah Bax Horton taking her grandfather’s cause into the 21st century, we culturally cannot let go of Jack the Ripper. You can chalk it up to a fascination with serial killers and true crime. You can attribute it to its inseparability from the “steampunk” vibes of 19th century London. And of course, it will be argued that the mystery of Jack the Ripper’s real identity is what keeps us coming back to the sordid tale.

But our fixation might well mask a deeper question raised by the story of the Whitechapel murders, one on which it’s far less fun to ruminate. Abberline’s cane—the one with the supposed face of the killer—is on display at the College of Policing not in the hopes that someone might walk past and suddenly solve the case but, rather, to inspire a reflection on that dark past and how far “advancements in police technology” have come.

Jack the Ripper, in absence of a biography of the killer to cling to, is instead a composite of the world he inhabited: the gaslights, the poverty, the easy prey, and the depravity that kept a country darkly fascinated. And as long as we must settle for the setting of the crimes in absence of facts about the killer, then staring at a carved face or corroborating medical records raises a question more lurid than, “Who was Jack the Ripper?”: that of “How did a supposedly great society allow such horrors to happen?”

And that’s a scarier thought than any walking tour or comic book could conjure.

You Might Also Like