Royal Navy Destroyers To Get Ballistic Missile Defense Upgrade

Newly combat-proven, having shot down Houthi drones over the Red Sea, the U.K. Royal Navy’s Sea Viper air defense system is poised to get an important two-part upgrade after around a decade in service. The first phase will focus squarely on capabilities to defeat anti-ship ballistic missiles, which the Houthis have become the first to fire in anger and present a real emerging threat.

The U.K. Secretary of State for Defense, Grant Shapps, today announced a new investment of £405 million (around $515 million at the present rate of conversion) in the Sea Viper. This, he said, will make the weapon “even more lethal against new and growing threats from hostile drones and missiles.” Installed in the Royal Navy’s six Type 45 destroyers, Sea Viper comprises a suite of two radars, a command and control system, and the Aster surface-to-air missile, a weapon that has also been used by the French Navy in recent engagements in the Middle East.

https://www.twitter.com/grantshapps/status/1749077259313435047?s=20

Work will take almost a decade and will be undertaken in two phases.

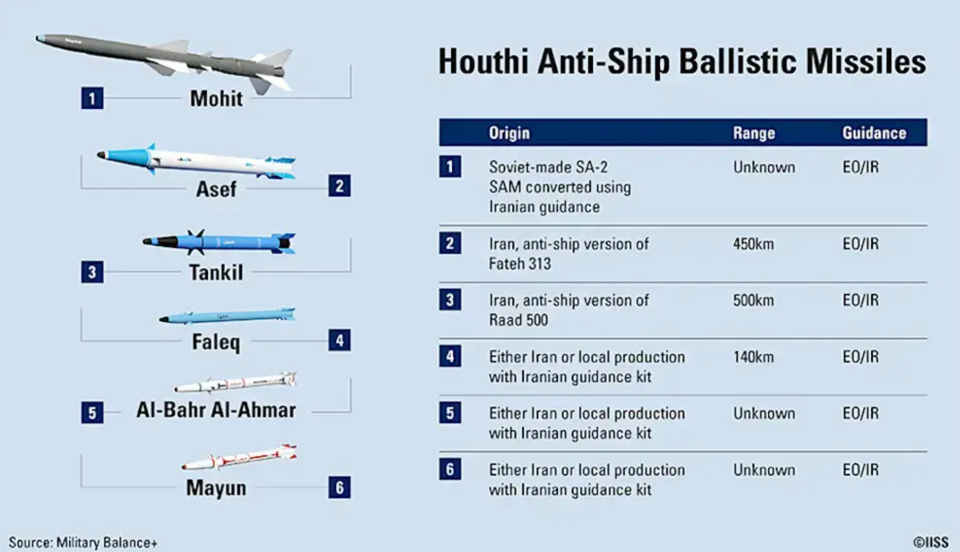

Under Phase 1, the Aster 30 missile will be modernized to improve its capabilities against anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), a relatively new type of threat that is also being employed by the Houthis in their campaign against shipping in the Red Sea. The Yemeni militant group is now regularly making use of its arsenal of ASBMs. However, the threat of far more advanced ASBMs is proliferating, especially in the Pacific, with China fielding a wide array of types, including very long-range examples.

Changes to the Aster 30 missile will include upgraded Block 1 warheads and new guidance and seeker software optimized for engaging ASBMs in the terminal phase of their flight.

The same phase will also address the Sampson multi-function radar — visible as a ‘spiky egg’ atop the main mast of Royal Navy Type 45 destroyers — as well as the command-and-control system and combat management system.

Phase 2 will see the evaluation of a new missile, the Aster 30 Block 1NT, currently under development by France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. This missile features a new seeker, which will further improve the ballistic missile defense capabilities of the Type 45 (and other warships armed with it).

In particular, Block 1NT will be better equipped to intercept medium-range ballistic missiles carrying maneuverable reentry vehicles (MaRVs), which you can read more about here. Capable of maneuvering and changing their trajectory at very high speed, these weapons are a particular challenge for air defenses.

Presumably, if trials are successful, the United Kingdom will order the Block 1NT missile to replace at least some of the Aster 30s now in use.

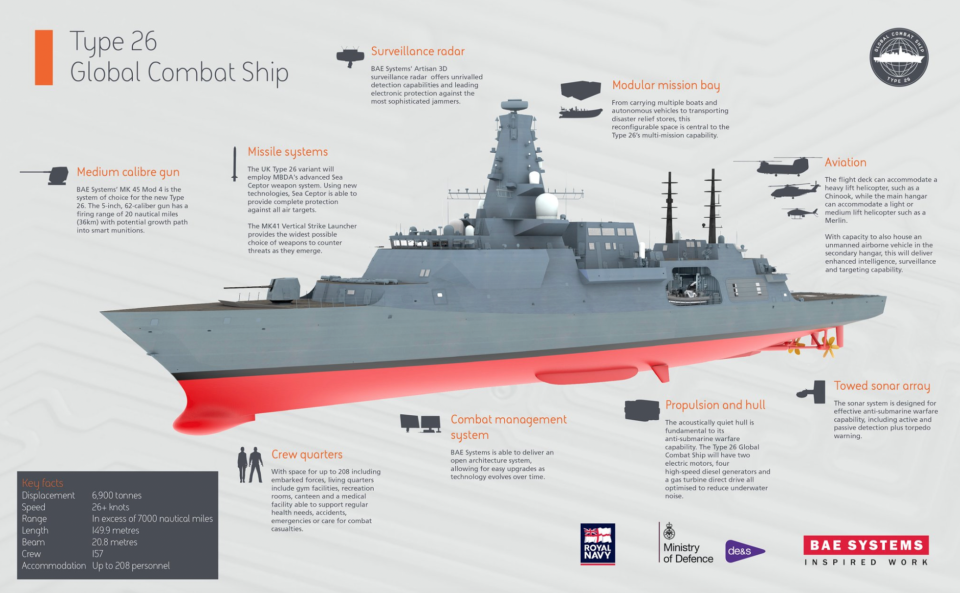

There had been speculation in the past that the Type 45s might receive the U.S.-made Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), in which would have allowed them to launch SM-2, SM-3 or SM-6 missiles for defense against ballistic missiles and hypersonic weapons, as well as support the fielding of Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAM). The upgraded Aster 30 and the potential addition of the future Aster 30 Block 1NT go some way to making up for not having SM-6, while the Mk 41 will meanwhile be installed in the new Type 26 frigates.

Even in its basic form, the Aster 30 is a potent air defense weapon. Except for the F-35B Lightning, the Aster 30, as the sharp end of the Sea Viper system, represents the Royal Navy’s outer air defense layer. Each Aster 30 is around 16 feet long and weighs approximately 1,000 pounds.

According to the Royal Navy, the Sea Viper is currently able to track “hundreds” of potential threats to an individual ship or task group at ranges up to 250 miles, using Aster 30 missiles to eliminate them when they close to “around 70 miles.” Other sources suggest the Mach-3 missile has a range of more than 75 miles.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jgh5CEjpCt4

There is also the Aster 15, weighing around 680 pounds, including its separate booster section, and with a range of around 18 miles, optimizing it for close-in and local-area and point defense. In the Royal Navy, the Aster 15 is being replaced by the Sea Ceptor, also known as the Common Anti-Air Modular Missile, or CAMM. You can read more about Royal Navy plans for this weapon here.

The Sea Ceptor upgrade for the Royal Navy's Typer 45 destroyers will see the addition of a new 24-cell vertical launch system array for those missiles. This will increase the overall vertically-launched missile capacity of these ships by 50 percent. The original 48 Sylver vertical launch system cells on these destroyers will be used exclusively for firing the longer-range Aster 30.

In the meantime, the complete Sea Viper system has already been used to successfully engage Houthi drones, as was announced by the U.K. Ministry of Defense on January 10 and that you can read about here.

On that occasion, the Type 45 destroyer HMS Diamond was reportedly responsible for shooting down seven of the 18 drones fired by the Houthis, using both Sea Viper and gunfire.

In the aftermath of those engagements, Grant Shapps said that, along with U.S. warships, HMS Diamond has been involved in successfully repelling “the largest attack from the Iranian-backed Houthis in the Red Sea to date.”

Reinforcing the threat that these drones (among other weapons) pose to warships, as well as commercial vessels, Shapps also suggested that HMS Diamond likely also came under Houthi attack, with the defense secretary saying:

“My understanding is that both the ship itself potentially was targeted … but also that there’s a generalized attack on all shipping.”

Fittingly, Shapps announced the Sea Viper upgrade following a visit to HMS Diamond in the Red Sea, where he thanked the ship’s company for their ongoing efforts to protect shipping in the region.

While the Sea Viper upgrade indicates the seriousness with which the the growing ASBM threat is being taken by the Royal Navy, it is part of a wider effort to improve the service air defenses against all manner of threats.

As well as the aforementioned Sea Ceptor upgrade, the Royal Navy is also testing laser weapons, intending to provide another (cheaper) method to destroy drones.

The Royal Navy announced last week that it had tested its Dragonfire laser-directed energy weapon, which it says promises to be able to down incoming drones, missiles, and aircraft at a cost of “no more than £10” per shot — around $13.

At this stage, there is no plan to install Dragonfire on any existing Royal Navy ships, but the service says it could be installed on those currently under construction, including the Type 26 and Type 31 frigates. There is also the possibility for a land-based version to tackle aerial threats for the British Army. Still, laser weapons have major limitations in range and effectiveness during various environmental conditions. Letting a potentially very hostile drone get close to the ship at all is a risk that may not be worth taking just to save a missile.

Regardless, an expanded range of air defense systems, and improved capabilities for those already in use is a welcome development for the Royal Navy. As the Houthis have demonstrated, even with their lower-end capabilities, the threat posed by anti-ship ballistic missiles is real. This is something to which many warships are vulnerable, especially if not under the umbrella of Aegis Combat System-equipped companions. Warships operating independently will increasingly need some level of capability against ballistic missile threats just to defend themselves.

So, while it isn't clear what capability, if any, exists today for the Type 45 to engage ASBMs, and what types, enhancing whatever is there is critically important.

A video shows a test of the Sea Ceptor missile:

Still, there remains a question over how realistic the longer-term plans for Type 45s and the rest of the Royal Navy's fleets are, amid constraints on budgets and crewing concerns.

Earlier this month, The War Zone described how the Royal Navy is so short on sailors that it is reportedly having to decommission two Type 23 class frigates to staff its new class of frigates. Such a move would reduce the service’s current fleet of 11 Type 23s to nine.

While this possibility might appear to cast doubt on the future plans to field a force of eight Type 26 frigates and five of the smaller Type 31s, it should be noted that the newer designs will have smaller crew complements, thanks to a greater degree of automation. The number of staff needed to operate nine Type 23s stands at 1,665, with the equivalent number for the larger planned fleet of Type 26s and Type 31s ranging from 1,656 to 1,756.

More worrisome, perhaps, is the short-term effect of reducing the frigate numbers. The situation in the Red Sea currently has demonstrated how quickly contingencies can emerge, while the Iranian-backed Houthis have shown how they can use missiles and drones to hold a significant portion of global maritime trade under threat. Responding to waves of strikes against targets in and around the Red Sea requires a significant number of warships (and aircraft), not to mention considerable stocks of appropriate weapons with which to engage the threats.

With upgrades for its Sea Viper systems now in the works, the Royal Navy’s Type 45 destroyers will at least be able to better respond to more complex scenarios involving ballistic missiles and other aerial threats, wherever they may occur.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com