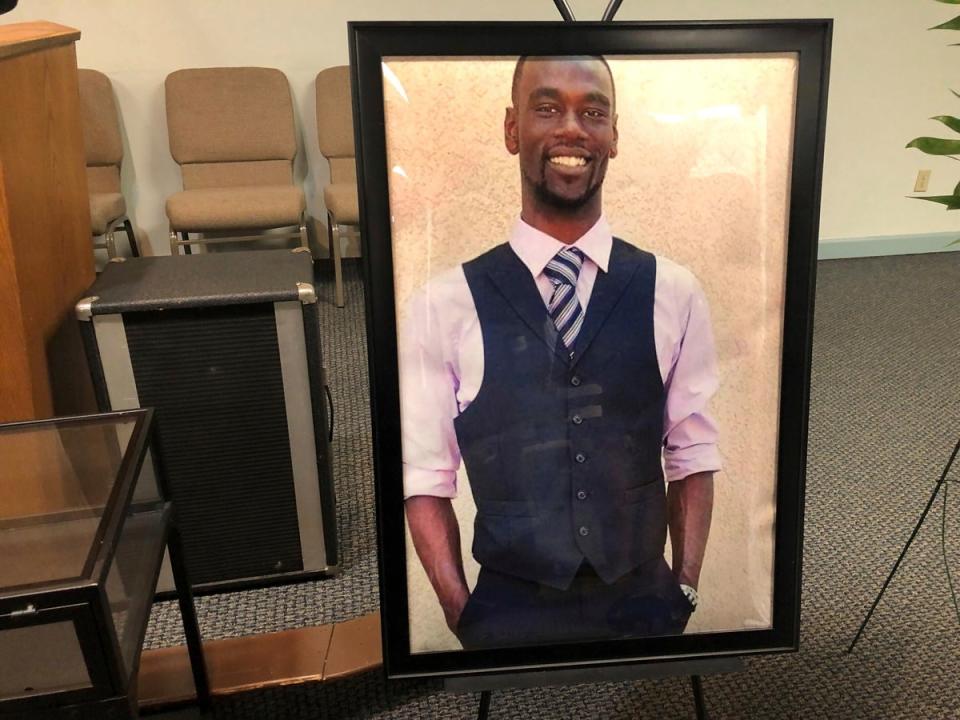

After Tyre Nichols’ death, can this bodycam AI make police more accountable?

How do you make a police force accountable in the age of Tyre Nichols? One company thinks the answer lies in AI.

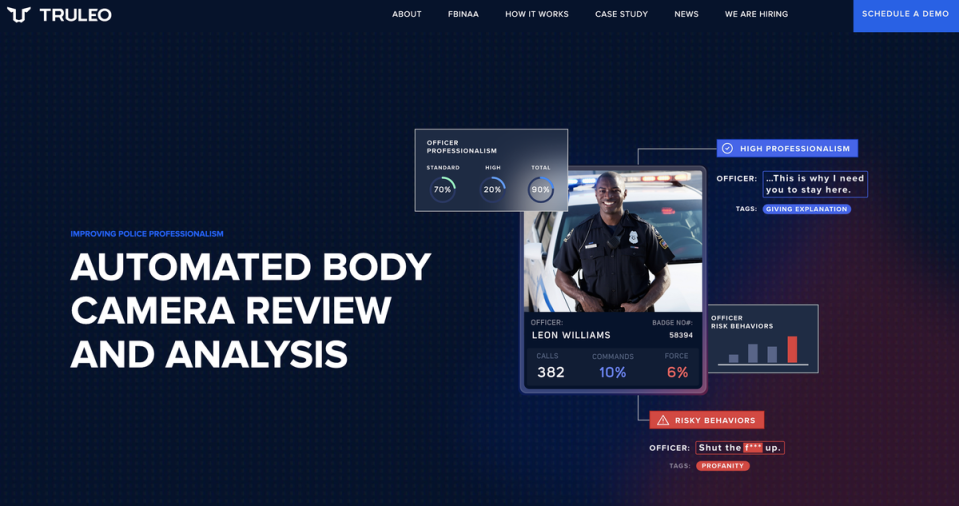

Truleo, a system that uses artificial intelligence to monitor audio from police officers’ bodycams and rate their interactions, is a tool that is supposed to prevent such tragedies from occurring. The tech has been getting a lot of attention since Nichols’ death, appearing everywhere from CNN to Axios. And CEO Anthony Tassone is bullish about its effectiveness, telling me on a Zoom call: “If Memphis PD had Truleo, Tyre Nichols would be alive today.”

Nichols was pulled over for a traffic stop in Memphis on January 27th. The 29-year-old father, who was on his way home, is shown in graphic and disturbing footage from a police body camera being pulled out of his car and wrestled to the ground. He tells officers, “I didn’t do anything,” and, “I’m just trying to go home,” while officers shout insults and threats (such as “I’m going to beat your ass”) and contradictory commands at him. officers hold him on the ground, chase him and then kick and punch him. Nichols calls for his mother as he is beaten. After he collapses, in clear need of medical attention, officers leave it longer than 20 minutes to render aid. The footage is hard to watch — and the officers who appear in it seem unconcerned about facing consequences for their actions. Once again, America has had to ask itself why its police are seemingly so unconcerned about basic accountability.

Tassone and his co-founder at Truleo, Tejas Shastry, used to work on Wall Street building the technology that analyzes phone calls (“We basically processed banks’ phone calls. If you call Bank of America, you might hear something like: ‘This call is being monitored for quality assurance purposes.’ We did that.”) While they worked there in 2020, George Floyd was murdered by a police officer and Black Lives Matter protests exploded across the nation. “And I’m from a law enforcement family,” says Tassone. “I’ve got family in the FBI, Homeland Security, combat veterans. You know, I went to college and they went to Afghanistan. And I was looking for a way to help cut through the noise of what happened with George Floyd. Really, everyone was trying to understand like, who are the good cops and who are the bad cops?”

One way to find out is by parsing through data that already exists in the cloud but is mostly never looked at, never mind analyzed. The body cameras routinely worn by police officers across the United States generate hundreds of hours of footage per year — 250 to 300 hours per officer, according to Tassone. And out of those 250 to 300 hours, “maybe one hour is going to get reviewed. And it’s going to be randomly sampled throughout the months. Could be a one-minute video from one month, a six-minute video from the next.” Tassone has worked with police departments across the United States, including Seattle, Alabama, Pennsylvania, Florida, Colorado, and California, while implementing Truleo technology. These include large, urban departments with hundreds of officers and small, rural departments with as few as nine. Consistently, he says, he finds that United States police departments are looking at “less than 1%” of their available footage from body cameras. At that point, he says, having the body cameras alone is just “a check-box exercise”.

Truleo makes use of the data that would otherwise be lost or ignored by analyzing officers’ words while they’re out on patrol, looking for red flags and green flags. Based on research that shows certain types of speech are more likely to escalate police interactions — threats, insults, swear words — the tech decides whether a cop on the street has done a good job or a bad job of interacting with citizens that day and assigns them “baseball card” type scores.

Tassone underlines that this means officers who behave appropriately and approach their job ethically will get a “virtual attaboy” and a positive record sent to their chief at the station, which should, in an ideal world, mean those officers are advanced to promotion above their more aggressive or unprofessional colleagues. But how does it relate to preventing a shocking situation like the killing of Tyre Nichols? “Those five officers, they didn’t make that decision that day to kill Tyre,” says Tassone. “They made thousands of decisions over time before that event happened. Their behavior would’ve deteriorated. There would’ve been so many flags on these guys for the language they use for different events. You know, maybe they’re involved in lots of uses-of-force events. Certainly the Tyre Nichols event itself would’ve lit up all over the dashboard of Truleo saying, Hey, there was a use of force, there was officer profanity, there was insults, threats. It would’ve lit up those videos. And the command staff would’ve been forced to deal with that.”

Unsurprisingly, Tassone believes in the ability of his own product to fix policing in America. He believes that understaffing across police departments leads to young, inexperienced officers being put into situations for which they are not anywhere near qualified. “By the way, I feel for those officers and I feel for their families,” he says, of the police who killed Nichols. “Tyre lost his life and the parents lost their son. Those officers lost their careers. And I think they should have never been in that situation. They’re totally too young to be in that situation. They clearly couldn’t handle that power and authority that they were given. And it should have been flagged a long time ago before these guys ended up murdering somebody — and now they’re going to go to jail.” For those affected by Nichols’ death — or indeed those who have simply had to watch the video, which was so disturbing that Nichols’ own mother begged people not to let their children watch it — that might be a difficult thing to hear from a man purporting to have solutions to America’s policing problem.

The truth is that four out of five of the police officers involved in Nichols’ death had prior violations at work, according to personnel records seen by NPR. Demetrius Haley, Emmitt Martin, Desmond Mills, and Justin Smith had all been either reprimanded or suspended in the past for behaving inappropriately on patrol. It’s safe to say that the chief of the department was aware they were not scoring a perfect “baseball card” and, whether AI tech had flagged these incidents or not, the humans at the top still acted as they did. Despite these infractions, all four officers were promoted into an elite squad known as the SCORPION team — a team of officers given the power to aggressively and proactively work to prevent and detect crime before it happens — which is how they came across Nichols, during a routine traffic stop that escalated horrifically.

The SCORPION crime suppression team — which has since been disbanded — was intended to “clean up” Memphis after a spike in crime. It’s true that standards for officers joining the team were lowered by the department following a drop in numbers of new police recruits, and that the five officers involved in Nichols’ death may never have ascended to the elite unit if there weren’t somewhat of a crisis in police recruitment, with applications falling year on year. But it’s also true that their previous violations were known and they were nonetheless promoted. Two of those officers, according to NPR, had violations that related to failing to report using force during arrests. That seems particularly pertinent, considering that research has shown units like SCORPION tend to use significantly more force against the public. In an article titled “AI can help in crime prevention, but we still need a human in charge,” ethicist and socio-technical professor David Tuffley writes: “When it comes to AI in policing, I believe there should always be a place in law enforcement for the finely honed instincts of an experienced human officer tempered by a system of checks and balances. The technology should always be subordinate to the human, taking the role of decision support helper." But what happens when the humans are just as problematic as the tech?

Truleo works with police departments that want to improve, either proactively or because they are already in a bad state. Torrance PD, in California, is a good example of the latter. The department is currently under review after allegations were made about discriminatory practices and excessive use of force, and racist texts that talked about killing Black suspects were leaked to the public. “Torrance had a lot of problems,” says Tassone. “They had some officers that had sent some text messages and done some things and they were getting rid of some horrific stuff.” He sees installing artificial intelligence as the first step toward true accountability, the kind that reassures an entire community. In this way, as Tassone sees it, something like Truleo is a “customer service”. The future of funding Truleo —which costs a small police department $50,000 per year, although their smallest department, the nine-officer Elizabeth precinct in Pennsylvania, spends only $5,000 — could even be in crowdfunding. “We want to do crowdfunding because I think a product like this is perfect for communities to have ownership in,” Tassone says. “The way we want to give ownership to communities is two ways. One, own the technology, own the company. You can own Truleo for as little as $100 and get equity in Truleo. And what I want to do is I want to have 5,000 or 10,000 people… that will go back to their city councils and demand that the mayor and chief of police have the courage to get body camera analytics.” Some might see this as giving power back to the people. Others might question whether it’s the people’s responsibility to pay to make their police forces more accountable.

Right now, however, the money for Truleo doesn’t come from community crowdfunding; it’s a venture capital-backed startup that raised substantial funds from Arnold Ventures. Arnold Ventures — co-founded by Laura and John Arnold, a former oil executive and investor respectively — touts itself as a philanthropically minded VC that aims to “maximize opportunity, minimize injustice”. Laura and John “really care about measuring impact, and for us, they asked the right questions,” says Tassone. “They wanted Truleo deployed, and they wanted academic studies created.” (Truleo recently released a case study from Alameda PD, authored by Tassone’s co-founder Shastry, that shows a 36% reduction in use of force by officers after the implementation of body camera analytics technology.)

Many might justifiably ask whether someone from a “law enforcement family”, backed by venture capital from a former oil executive and an investor, is the right person to fix policing in 2023. Tassone clearly believes in bringing policing back to the community – but he also believes in the fundamental ability for a police chief to make the right calls once presented with the data. He also thinks that the root cause of much police violence is officer stress and a lack of training. Left on the table are slightly less savory questions we might have to ask about police culture, such as: Which kinds of people are attracted to such a profession? How does qualified immunity affect how officers approach the citizens they’re supposed to serve? Why is there still a lack of standardized training for officers nationally? Why do so few officers have any experience at all in de-escalation techniques? Why has the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021, which sought to provide some federal oversight and ban the use of chokeholds and no-knock warrants in exchange for extra funding, still not passed? And, considering we know that chiefs still routinely promote officers who have acted inappropriately – sometimes even who have killed people – is the problem really a lack of technological opportunity, or a culture that is rotten to its core?

Human decisions not just in hiring and promotion but in strategy – such as in the creation and proliferation of SCORPION-type units, which are known to generate more complaints from the public and to promote aggression – will clearly remain a problem, even with the most advanced of AI at our fingertips. Indeed, it’s not long since body cameras themselves were seen as a panacea to the police violence problem; yet the officers who killed Nichols were all wearing body cameras, and were aware that their actions were being filmed. They were, additionally, standing directly underneath a “crime-fighting camera” attached to a lamppost that filmed their every move. That’s the reason why so much footage has been generated of Nichols’ death and the actions that led up to it.

Derek Chauvin, who murdered George Floyd, was the subject of multiple official complaints and had been involved in several police shootings before he went on to kill Floyd by kneeling on his neck. His “baseball card” score must’ve looked appallingly bad. AI might have helped flag the incident in real time, possibly even preventing it from ending in Floyd’s death. But without human accountability, AI is as useless as any other technology that was supposed to solve the exact same problem.