U.S.-backed effort to fight Colombia money laundering has so far been a flop

Drug cartels must move money between the consumers of cocaine—mainly in the United States and Europe — and the producers in the Americas. Their ability to do so is a vital part of the illicit industry.

So when the Colombian Attorney General’s Office, known as Fiscalia, announced in July 2022 that the South American nation was going to vastly change the way that large-scale money laundering cases would be investigated, it was welcomed.

It was a big deal, a specialized unit and based on a model created next door in Panama. The initiative envisioned a highly trained task force of police, prosecutors and financial experts. They’d be trained by the U.S. State Department and work in a close partnership with the FBI.

In a message posted on the Fiscalia Instagram account, the Attorney General’s Office vowed that the task force would target the intersection of crime and corruption and would “affect criminal networks of transnational scope that resort to financial and commercial maneuvers to hide their illegal actions.”

Attorney General Francisco Barbosa Delgado also appeared on Fiscalia’s YouTube channel, vowing to go after “economic and financial crimes that are the link for criminal conduct associated with corruption and facilitate the diversion and concealment of public and private money.”

But after 17 months — almost two-thirds of the time allotted to the two-year-program — and a change in presidential administrations in Colombia, what has emerged is not the crack unit once envisioned.

“To be clear, Colombia does not have an anti-money-laundering task force,” said a US official, on condition of anonymity in order to discuss sensitive bilateral matters. “They’re in communication with us regarding that issue, and we support different anti-money-laundering efforts, but a specific task force … does not yet exist in Colombia.”

Details about the task force were revealed in the Nov. 6, 2023, release of the NarcoFiles, a collaborative investigation involving reporters from 32 media outlets, led by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. Reporters pored over 13 million documents leaked from the Colombian Attorney General’s Office.

Found among the documents was the final draft of the Memorandum of Understanding between the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs and the Colombian Attorney General’s Office. That document outlined exactly how the task force would operate.

It would:

▪ Advance efforts to increase prosecutions in cases of complex schemes of money laundering and related crimes.

▪ Promote strategies to increase seizures in cases of money laundering and related crimes.

▪ Create a permanent elite team for research and prosecution of complex money-laundering schemes and related crimes.

The program was so far along that a floor plan for office space had been prepared for the task force, patterned after one in neighboring Panama. The Panama effort became a model, with the Dominican Republic agreeing in April that it too had signed a deal with the State Department to create an anti-money-laundering task force.

Luis G. Moreno, now a retired U.S. diplomat, helped launch a security partnership with Colombia as the director of the Narcotics Affairs Office in Bogotá. Going after the money was key in defeating cartels decades ago and the tactic remains just as important today, he said, lamenting the apparent inaction by the Attorney General’s Office.

“It’s absolutely crucial and it was successful in the past against the Cali Cartel and to a lesser extent against Pablo Escobar because he was not as organized and centralized,” said Moreno, who served as U.S. ambassador to Jamaica during the Obama administration. “But yes, I don’t know why they got away from it.”

Colombia is a major Latin American recipient of U.S. foreign aid, bringing in more than $13 billion since 2000, much of it for Colombia’s military and in support of counter-narcotics efforts that further the mission of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

READ MORE: Explore the NarcoFiles project

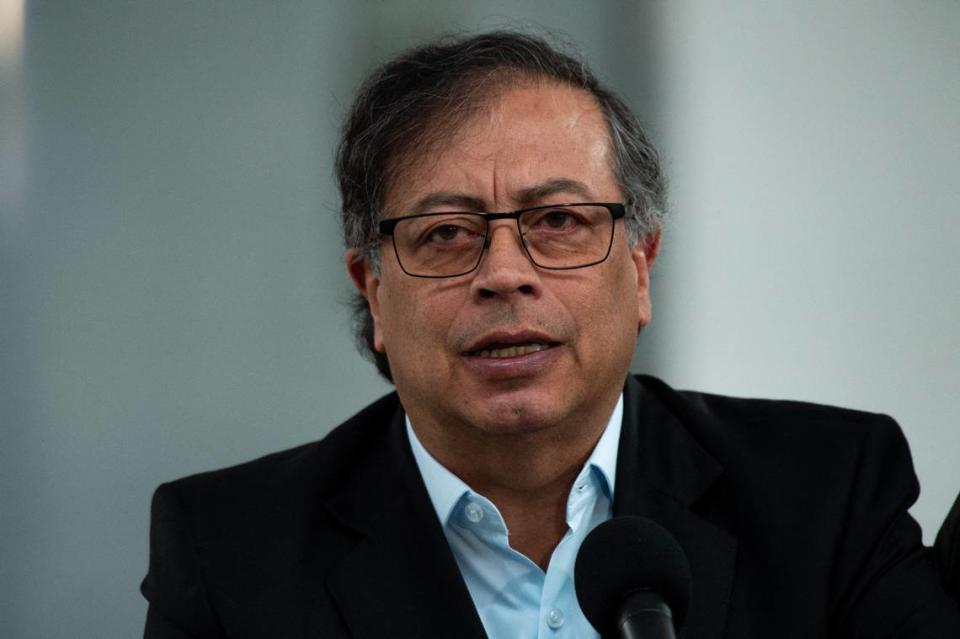

Since his June 2022 election as Colombia’s first left-wing president, Gustavo Petro has been vocal about what he’s described as Washington’s “failed” half-century “war on drugs.” It has brought nothing but violence and bloodshed while failing to curb demand, the Colombian leader has repeatedly said.

In September, during the Latin American and Caribbean Conference on Drugs in Cali, he proposed an alliance among the region’s leaders to have “a different and unified voice” in order to shift the fight away from a militarized approach to one that recognizes drug consumption as a public health problem. But in a statement the group issued at the end of the conference, they also agreed there’s a need to break the links between drug trafficking and other illicit criminal activities, including money laundering and corruption.

The Colombian prosecutor’s office has acknowledged that the task force is not fully operational, but claimed it was not the agency’s fault.

“We are working in coordination with the United States Embassy so that members from other institutions can join the group, but the final decision to assign officials is not the responsibility of the Attorney General of Colombia,” the agency said.

A U.S. Embassy spokesperson in Bogotá confirmed efforts with Colombian partners to establish a task force to investigate and prosecute money laundering crimes.

“At this stage, it is premature for us to discuss details of these efforts, but we are committed to strengthening these bilateral efforts to disrupt money launderers and bring them to justice,” the spokesperson said, looking past the delays.

The Colombian Attorney General’s Office did note that two prosecutors and four researchers were appointed to the task force, and it has investigated some cases. But that pales in comparison to what has been accomplished in neighboring Panama.

The agency’s stance also contradicts the Memorandum of Understanding, which stated that the Colombian authorities were solely responsible for creating “an investigative group…with an elite team of analysts, investigators and prosecutors.”

U.S. officials complain of a “glass ceiling” in combating money laundering. Often certain individuals are untouchable due to their political connections.

The failure of the Colombian government to ramp up the task force illustrates the difficulties that law enforcement officials face, both in the United States and countries like Colombia, when trying to crack down on illicit activities that involve complex financial transactions.

“Colombians are eager to cooperate on cases, but they don’t initiate investigations on their own,” complained a former DEA officer who worked closely on money-laundering cases, demanding anonymity to speak on the sensitive matter.

In a 2018 report, the International Monetary Fund said among the issues Colombia faces in trying to crack down on such cases is that “operational cooperation is partially fragmented and inadequately coordinated” and specific measures to prevent or mitigate money/terrorism financing risks “depends on a wider decision of the government.”

The report also identified a problem that the task force is was supposed to address, which is the lack of an existing framework to investigate complex cases, namely that there is no framework in place to investigate complex cases.

“Colombian authorities can investigate and prosecute money laundering through a wide range of legal tools and well-resourced investigative bodies. Nevertheless, most of the cases involve simple money-laundering schemes comprising low amounts of funds,” the report said. “Most cases that are investigated and prosecuted are related to illegal drug trafficking and few involve pursuing money laundering originating from other predicate crimes.”

Colombia does focus on money laundering through a number of existing programs, but the new initiative targeted complex cases.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2021, the cultivation of coca plants — the main ingredient in cocaine — reached 504,100 acres in Colombia, the largest area since the U.N. began tracking this data in 2001.

This is what prompted Petro, just a month after his inauguration, to call the war on drugs “a failure,” in a statement in September of 2022 and later in an interview with French television. Ironically, the statement came just a few months after the independent Attorney General’s Office had announced the anti-money-laundering partnership. Petro argued the costs to rural Colombians, racked by violence and forced crop eradication, has been too high.

Drug cartels rely just as much on a secure network to launder money as they do to transport the illegal drugs themselves. Money laundering is a lucrative industry of its own, serving not only drug cartels and other criminal organizations, but also entities such as corrupt politicians and wealthy individuals looking to evade taxes.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has estimated that between $800 billion and $2 trillion is laundered each year. In Colombia, the government’s Financial Information and Analysis Unit flags around 20,000 suspicious transactions valued at roughly $5 billion every year, Director Javier Gutierrez told news agency Reuters last year.

Kevin G. Hall of OCCRP contributed to this report.