U.S. and Haiti investigations into Jovenel Moïse assassination offer stark differences

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

U.S. and Haitian authorities agree that a pastor’s ambition to rule Haiti three years ago led to the shocking assassination of the country’s president, Jovenel Moïse.

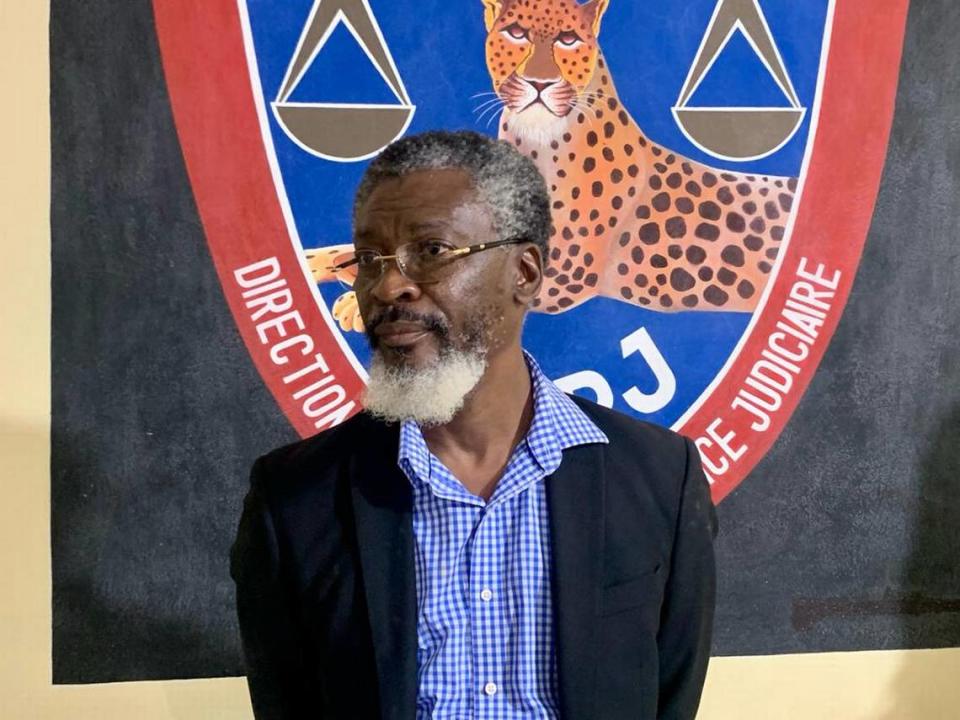

But the two nations’ investigations diverge on whether Haitian-American minister Christian Emmanuel Sanon played a leading or supporting role in the slaying. Sanon, arrested in Haiti after Moïse’s death on July 7, 2021, is being held in a federal lock-up in Miami. He’s accused in Haiti of collaborating with Miami-area security contractors and recruiting former Colombian soldiers to force Moïse from power using an illegal arrest warrant so Sanon could replace him.

In the U.S. Sanon, 65, is charged with violating export laws by smuggling bullet-proof vests for the Colombian commandos before the killing and plotting a “military expedition against a friendly nation,” a violation of the U.S. Neutrality Act. He faces a maximum sentence of 10 years.

Those offenses contrast sharply with the more serious accusation of conspiring to kill Haiti’s president, a charge other defendants in Miami face that carries a possible life sentence.

In the Haiti investigation Sanon is viewed as the catalyst for the assassination, and he’s at the top of the list of a dozen suspects described as “authors” of the plot. Haitian authorities agreed a year ago to extradite Sanon to the U.S. , where he was charged with the less serious smuggling and Neutrality Act offenses.

While Sanon awaits trial in Miami and one of his fellow Haitian Americans charged in the case, Joseph Vincent, was sentenced Friday to life in prison after pleading guilty to the murder conspiracy, the slow-moving Haitian inquiry is finally reaching its conclusion.

After two-and-a-half years, Haiti Investigative Judge Walther Wesser Voltaire is preparing to issue formal charges and has shared some of his findings with Port-au-Prince prosecutor Edler Guillaume. A leaked 31-page document penned by Guillaume shows that Haiti’s investigation overlaps to some extent with the U.S. case. Guillaume is recommending that seven suspects charged in Miami also be charged in Haiti.

Similarities and differences

But there are major differences in the investigations. Haitian authorities are targeting a much broader range of suspects within their own country, including Sanon and others who were personally and politically close to the slain president.

Evidence discovered after Sanon’s arrest at his Port-au-Prince home in the days following the assassination makes it “appear that he is indeed the main author of the crime perpetrated against President Jovenel Moïse,” Guillaume wrote in his report for the judge.

READ MORE: How a Miami plot to oust a president led to a murder in Haiti

Guillaume is recommending formal charges against about 70 people. Among them: the president’s widow, Martine Moïse, who was wounded during the fatal shooting of her husband; his former prime minister, Claude Joseph, and former national police chief Léon Charles. While the members of Moïse’s inner circle are accused of complicity based on testimony that they were aware of a plan to arrest the president, a dozen others, including Sanon, are looking at charges of murder, attempted murder, illegal detention and illegal possession of firearms and ammunition, along with criminal association and waging a conspiracy against the security of the state.

Martine Moïse, the subject of an arrest warrant in Haiti after she refused Voltaire’s invitation to appear before him, has blamed others for her husband’s murder, while Charles and Joseph have previously denied any involvement.

Dubious claims of U.S. involvement

Ultimately, it is up to Voltaire to decide who will be formally charged in Haiti’s case. But interviews with people familiar with his inquiry suggest that unlike federal authorities in Miami, Voltaire is focusing heavily on Sanon, a pastor and physician in Haiti who has also lived in Florida. The judge views Sanon as a major player in the deadly plot, citing his meetings with pastors and politicians in Port-au-Prince as well as security contractors and financial backers in South Florida. Voltaire, who highlights Sanon’s ambition to become Haiti’s president, also cites his contacts with key suspects either personally or through emissaries.

Among the suspects who fingered Sanon as the head of the plot: former Haitian government official Joseph Félix Badio, who was arrested in October and is in custody in Haiti, and James Solages, a Haitian American who was extradited from Haiti and is awaiting trial in the Miami case.

Solages told Haitian authorities that in March 2021 Sanon called asking for his help and promised him a payment of $80,000, allegedly to serve as an interpreter. Solages testified that Sanon informed him that he had been chosen by the U.S. State Department to lead a presidential transition in Haiti — a claim that was untrue.

In his report, the Haitian prosecutor mentioned the promised payment to Solages, and said Sanon himself admitted to recruiting “national and international attackers,” and had weapons and ammunition in the house where he was staying in Haiti.

“In view of the evidence of the facts put forward, it can be deduced that the accused Christian Emmanuel Sanon is one of the main perpetrators of this villainous crime,” Guillaume concluded.

At the time, Moïse was ruling by decree and facing growing opposition protests. Despite the political climate, there was no effort by the U.S. government to remove him from office. In February 2021 the Biden administration publicly supported Moïse’s claims that his presidential term didn’t end for another year.

Still, the suspects used the cover of official U.S. support to pull off the killing, which initially was planned as an arrest or kidnapping of the president. An illegal 2019 Haiti warrant issued by a judge was used to recruit the Colombians and to lead people to believe Moïse was wanted by U.S. authorities. When the assault was finally carried out, Solages yelled out, “DEA, U.S. Army operation.”

‘The last desperation effort’

Zeljka Bozanic, Sanon’s Miami attorney, said although she’s unfamiliar with the Haiti investigation, he was not the mastermind of the conspiracy to kill Moïse.

“Whatever case they’re trying to put together in Haiti seems to be different from the case in Miami,” she told the Miami Herald. “He is not charged with being the mastermind in the Miami case. It is clear he was not the mastermind.”

During a September detention hearing for Sanon in Miami federal court, prosecutor Monica Castro and FBI Special Agent Mike Ferlazzo portrayed the married father of three as a politically ambitious pastor and physician who plotted with a circle of people in South Florida and Haiti to install himself as president after Moïse’s removal from office.

But they said that his involvement in the plot became limited after a botched June 14, 2021, attempt at the Port-au-Prince international airport to arrest Moïse upon his return from a trip to Turkey.

After the fiasco, U.S. prosecutors said, Sanon’s co-conspirators abandoned him as the president’s replacement, partly because he could not legally qualify because of his dual citizenship in Haiti and the United States. Instead, the main co-conspirators opted to replace Sanon with a justice on Haiti’s Supreme Court who was on board with the plot to kill him, according to Castro and Ferlazzo.

At that point, despite his continuing ambitions to be Haiti’s next president, Sanon was apparently unaware of the main group’s strategic shift to kill Moïse instead of arresting him, Castro and Ferlazzo said during the detention hearing in the Miami case.

Ferlazzo was asked whether Sanon was present at key meetings in early July 2021 with the main co-conspirators in Haiti where they solidified the new strategy to kill the president.

“If you’re asking specifically if he was a party to the conversations in … July, I do not have evidence of that,” Ferlazzo said.

“Wouldn’t you agree with me that the plan was changed in the last minute … to kill the president sometime in — a few days before the killing in July?” Bozanic, asked the agent.

“So, yes,” Ferlazzo said, “ultimately the last desperation effort was for a kill mission.”

Ferlazzo’s testimony underscores why U.S. prosecutors did not charge Sanon with conspiring to kill Haiti’s leader.

Haiti case stymied by uncooperative witnesses

At the time of Moïse’s death, Haiti was already struggling to control surging gang violence, kidnappings and a political crisis. Since then, the situation has grown worse. Meanwhile, efforts to investigate the president’s killing have been marred by corruption allegations involving the first of five investigative judges, an attempt by another prosecutor to charge current Prime Minister Ariel Henry on accusations he communicated with a key suspect on the night Moïse was killed, and calls by Martine Moïse for Voltaire to be recused.

READ MORE: Who was involved in killing of Haiti president Jovenel Moïse?

In addition to Haiti’s former first lady refusing to be interrogated, the Haitian inquiry has also failed to get the cooperation of other witnesses and jailed suspects, and suffered from a lack of information from U.S. investigators and prosecutors. The federal judge overseeing the case in Miami issued a protective order banning prosecutors and lawyers from sharing evidence with Voltaire, the investigative judge, and other authorities in Haiti.

Voltaire has struggled to get Haitian government and banking records for his investigation. Some of the police officers involved in the initial investigation have left Haiti. The obstacles have meant that Voltaire has been forced to rely on testimony from individuals who have lied and contradicted themselves, according to the Haitian prosecutor’s report.

More than 40 people have been arrested in Haiti for Moïse’s murder, including 18 former Colombian soldiers recruited for the deadly assault and numerous Haitian policemen taken into custody for standing down during the attack or doing nothing to prevent it. Among them: the head of the presidential security unit, Dimitri Hérard, and his boss, presidential security coordinator Jean Laguel Civil. So far, no one in the Haitian investigation has been officially charged.

Co-conspirators in Miami may be charged in Haiti

Defense attorneys for several men indicted in Miami who are also expected to be charged as leading participants in the Haiti assassination case said their clients will likely never be turned over to Haitian authorities after pleading guilty and cooperating with U.S. prosecutors.

The Haiti investigation is recommending charges against seven of the co-conspirators indicted in Miami. They include Sanon, Solages, Vincent and Haitian businessman Rodolphe Jaar, along with two retired members of the Colombian military, Mario Antonio Palacios Palacios and Germán Rivera Garcia. All but Sanon and Solages have already pleaded guilty and are cooperating with U.S. authorities.

“The Haitian government may charge certain people named in the Miami indictment, but I can’t envision their efforts will bear any fruit,” said attorney Brian Kirlew, who is representing former Haitian senator Joseph Joël John.

John has pleaded guilty in the U.S. case to conspiring to kill Moïse and hopes to get his life sentence reduced as a cooperating witness. Known in Haiti as John Joël Joseph, the former lawmaker is also considered a key player in the Haitian inquiry. However, he is one of three suspects who escaped from the country before authorities could question them.

“The reality is, they cannot provide for the security and safety of the defendants in Haiti,” Kirlew said. “The U.S. government also would not turn over the defendants convicted here until they have completed their prison sentences.”

The U.S. investigation has moved quickly. Five of the 11 defendants originally charged in the case have pleaded guilty and face life sentences for conspiring to assassinate Moïse. A sixth defendant, Tampa-area businessman Frederick Bergmann, pleaded guilty Friday to conspiracy charges involving backing a military expedition against a friendly nation and smuggling bullet-proof vests from South Florida to Haiti for the Colombian commandos who executed the deadly assault. The maximum prison term under his plea deal is 10 years.

Bergmann, who owned an export business in Tampa that shipped medical supplies to Haiti, coordinated the shipment of ballistic vests with Sanon in the months before the Colombian commandos carried out the assassination.

Bergmann is not even mentioned in the Haitian prosecutor’s report — nor are two principals of a Miami-area company named CTU Security, Antonio “Tony” Intriago and Arcángel Pretel Ortiz, who were hired by Sanon to recruit the former Colombian soldiers to provide security for him in his quest to replace Haiti’s president. Also not mentioned: Broward County businessman Walter Veintemilla, who provided a $175,000 loan to CTU for Sanon’s protection. Those three men have been charged in the Miami case with conspiracy to kill Haiti’s leader.

Miami attorney Walter Norkin, a former federal prosecutor who worked on the U.S. investigation into Moïse’s assassination, said the FBI-led investigation in South Florida is significantly different from the one in Haiti for several reasons.

For starters, the countries’ laws apply differently. Second, the U.S. case is narrower than the Haitian case because the FBI and prosecutors have focused on a smaller group of people accused of hatching a scheme from South Florida to carry out a violent coup against Haiti’s president. By comparison, the Haitian case doesn’t have those limitations because investigators are focusing on who plotted the assassination in that country, who participated in killing Moïse at his home, and who stood to benefit politically from the deadly attack.

“The U.S. jurisdiction over this crime is limited by what statutes are specifically applicable to the charged facts, which involve the assassination of a foreign head of state in a foreign country,” Norkin told the Herald. “In contrast, Haitian jurisdiction is much broader because it was the president of Haiti who was assassinated in Haiti.

Norkin, a partner with the Akrivis Law Group’s offices in Miami and New York, also explained the U.S. interest in the case.

“If no U.S.-based actors were involved and there were no events that took place in the U.S.,” he said, “there would not be a U.S. investigation and prosecution.”