The U.S. Never Successfully Fielded an Instant Foxhole Bomb, But Russia Sure Did

The U.S. Army has repeatedly tried and failed to develop an explosive device capable of making a ready-made foxhole.

Russia has reportedly fielded such a device: the OZ-1 high-explosive entrenching tool.

Recent advances in warfare, including drones and small-caliber proximity fuses, may have made foxholes obsolete.

During the Cold War, the U.S. Army tried repeatedly to develop a foxhole bomb, an explosive device meant to instantly dig out a hole in the ground large enough for a soldier to shelter in. While the U.S. never successfully fielded such a device, the Russians did—and the device might make an appearance this winter in Ukraine. In the meantime, the foxhole is looking less attractive than ever thanks to advances in weapons technology, including drones and smart munitions.

✈︎ Don’t miss any of our best-in-class military and defense news. Join our squad with Pop Mech Pro.

Still, the foxhole is one of the most ubiquitous fighting positions on the modern battlefield. Individual soldiers dig the hole in the ground, typically about armpit deep. Using the earth itself as protection, the foxhole’s purpose is to allow troops to defend a position that otherwise has little to no cover or concealment. Foxholes offer safety from direct fire in the form of small arms fire, tank guns, and rockets, as well as indirect fire, including cannons, mortars, and rocket artillery.

Foxholes are both loved and hated. Loved, because they are often the only thing sheltering an infantry soldier from enemy fire. Hated, because soldiers have to dig the hole themselves, and an army on the move might require a soldier to dig several foxholes a day, armpit deep, again and again.

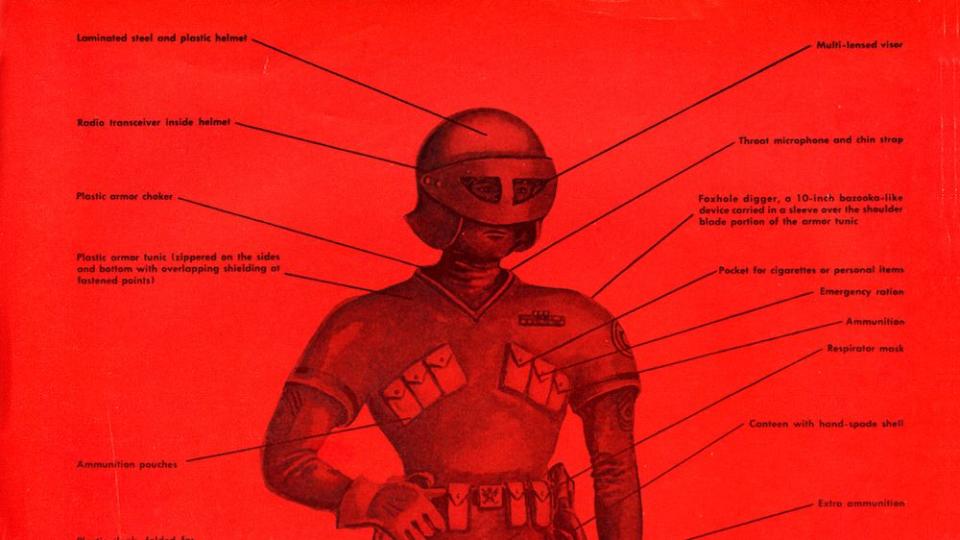

In the 1950s, an instant foxhole-digging device was one of the most persistent ideas for improving soldiers’ lot. A soldier would carry a small, compact explosive device and, when the order came to dig, use it to create an instant fighting position. Decades ago, the device was a frequent piece of kit featured in “soldier of the future” articles. In the image below, published in the November 1956 issue of Army magazine, the soldier carries an “automatic foxhole digger, a miniature bazooka that propels an explosive charge into the ground. This will result in a hole that can be quickly improved with a light hand spade.”

There were a number of reasons why the instant foxhole concept endured. First, the nation was in the midst of the Space Age, and all sorts of high-tech ideas, from jet engines to rockets and satellites, were coming to fruition for all sorts of fighting men—with the notable exception of ordinary infantrymen, whose kit remained almost completely unchanged from World War II. Second, President Eisenhower’s “New Look” defense strategy relied heavily on nuclear weapons, and a soldier might be required to dig a hole very quickly to shelter from a nuclear attack. Third, the Army’s World War II field leaders were gradually coming up through the ranks, and these colonels and generals, captains and majors, didn’t like digging foxholes either.

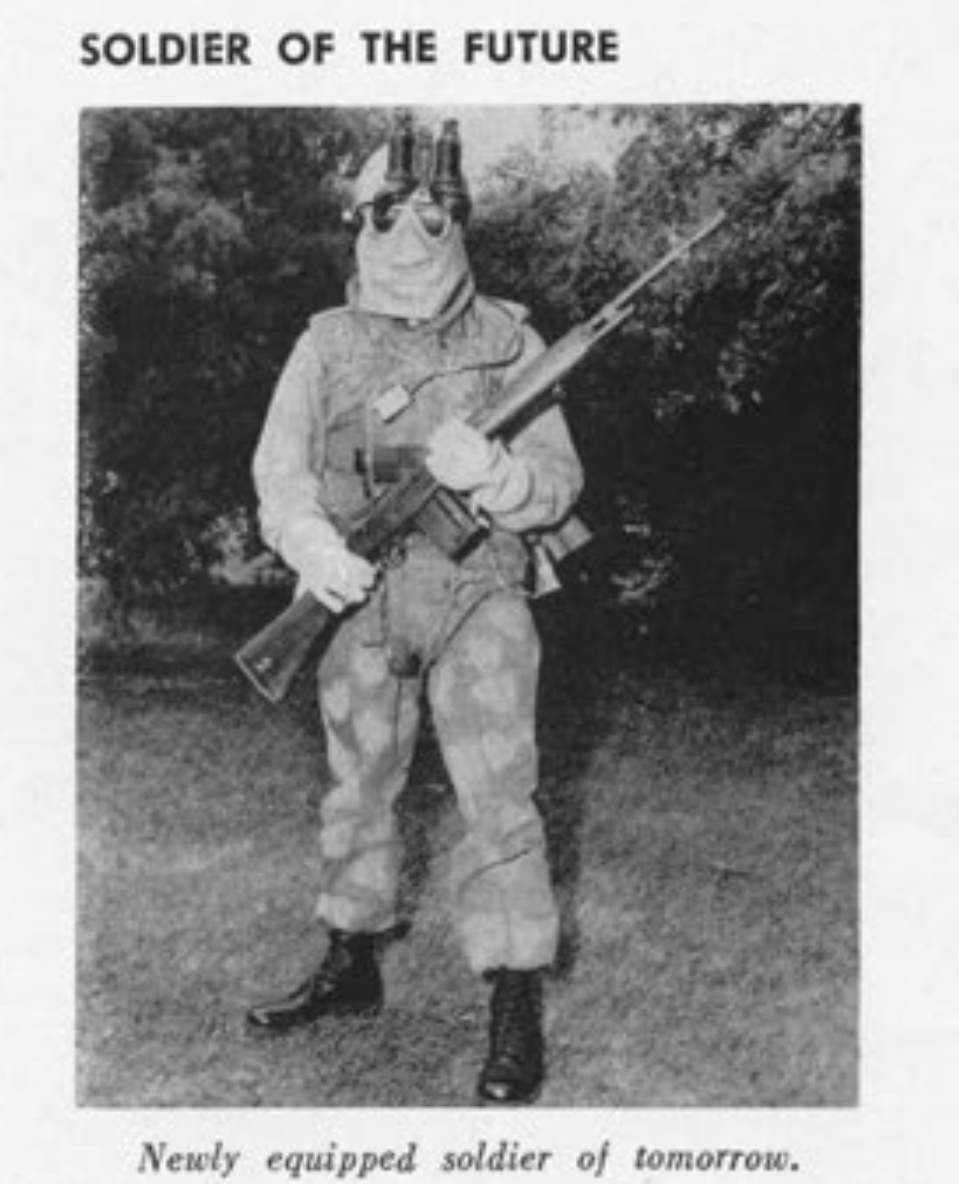

In 1959, the October issue of Military Police Journal ran a different article on the “Soldier of the Future,” which was a bit less fanciful than the concept displayed in Army magazine. “Further protection is provided by explosive fox-hole diggers, which he carries slung across his back. In the event of impending nuclear attack, and provided he is warned in advance, he need only to implant his explosive fox-hole digger, ignite the fuse, and wait for the blast. The resulting hole in the ground will give him below-ground-level protection.”

By 1959, Popular Science had run an article showing the device in trials at Fort Hunter-Liggett in California. The device (pictured at the top of this story) is advertised as “safe enough to be dropped with a paratrooper.” It still required a soldier to finish the hole by hand, but reportedly cut the amount of time needed to create a foxhole from 30 minutes to just four minutes.

The article hinted that the device was less-than-totally effective, stating that it was “admittedly experimental” and a “better one is in the hopper.” There’s no evidence this explosive foxhole digger was ever issued to the U.S. Army or Marines. By 1965, however, Vietnam captured the Pentagon’s attention, because the style of warfare—patrolling against guerrillas and using helicopters to transport fighting men from one location to another— made foxholes less useful.

As the Army moved on from Vietnam, the explosive foxhole bomb bubbled up again in the early 1970s, this time with a request from the storied 82nd Airborne Division. The service developed a device that used two explosive charges in quick succession, the first a small shaped charge to make an initial hole in the ground, and then a larger cratering charge. According to the Army Corps of Engineers, the five-pound, 27-inch-long device was only briefly in production due to “unacceptable reliability and other problems, including acoustic and visual signatures.” In other words, the explosions were easily visible and easily heard, potentially tipping off nearby enemy troops. The number of explosions could also tip off enemies to the number of friendly troops.

A hand auger was proposed as an alternative to the shaped charge, but it was slower and the cratering charge still made noise. Another problem with the device was that some soils and conditions needed larger or smaller charges, and while large charges might do the trick in all environments, they would also be heavier and less safe for soldiers not trained to handle high explosives. As the Corps of Engineers noted: “Permafrost is very difficult and an item that will perform satisfactorily will cause an ‘overkill’ in almost all other situations.”

The U.S. Army never did field a foxhole bomb, but another army did. Much of Russia freezes over in the winter, making foxholes a higher priority. Collective Awareness to Unexploded Munitions (UXO), a nonprofit that raises awareness of the dangers of unexploded weapons on the battlefield, recently shed light on the Russian OZ-1, a “high-explosive, shaped-charge entrenching tool.” The OZ-1 is designed to create a larger hole for two to three occupants, and at 38.8 total ounces of high explosive, it has three times as much power as the failed American design (12.48 ounces). The OZ-1 might make an appearance this winter in Ukraine—if the war drags on that long.

Foxholes are easy and effective protection on the battlefield, but new technology could render them obsolete. Armies are fitting inexpensive quadcopter drones with hand grenades, allowing drone operators to drop them from above directly into a foxhole or a trench. Small-caliber, rapid-fire cannons such as the XM813 Bushmaster chain gun (above) can electronically program their 30-millimeter rounds to explode over foxholes, peppering those inside with lethal shrapnel. If the U.S. Army ever gives the foxhole bomb another try, it will to have to come with a roof to keep unwanted elements out.

You Might Also Like