How a U.S. Senator from Minnesota became a key player in a Nazi plot

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

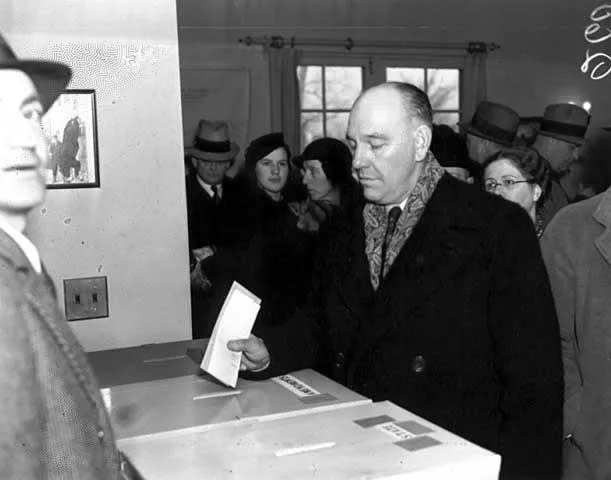

WASHINGTON — When former Minnesota U.S. Sen. Ernest Lundeen was killed in a plane crash in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains on Aug. 31, 1940, he likely knew the Justice Department was investigating his part in a Nazi-driven plot to overthrow the U.S. government.

Lundeen’s secretary, who was tasked with driving the senator to the airport for that ill-fated trip, testified to the FBI that she found Lundeen in his Capitol Hill office crying inconsolably. The senator would not say why.

According to the secretary, “I’ve gone too far to turn back,” was about all Lundeen said.

The cause of the mysterious crash was never resolved. Lundeen, 62, was among 25 passengers of the plane, which also carried two FBI agents and another Justice Department official.

All passengers and crew on the plane perished. But miraculously, a copy of the speech Lundeen planned to give at a Labor Day event in Minnesota was found unscathed in the Virginia countryside, which was scattered with body parts and debris from the crash. It was not written by Lundeen, however, but by an agent of Hitler’s government who paid the Minnesota senator to promote Nazi propaganda.

That’s just part of the story that MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow tells in an eight-part podcast called “Ultra” that uncovers a series of seditious plots to sow discord in the United States 80 years ago. The plots also included plans for a violent overthrow of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to impose a fascist dictatorship in the United States.

The story, unearthed while the nation is still trying to grapple with the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, is a reminder that democracy in the United States has been under threat before. The story also shows how the Justice Department failed in its effort to punish most of those involved, and it was the American people at the ballot box who removed many conspirators from power.

Lundeen was not a part of the efforts to commit violence. His role was to use his talents as an orator – in 1905 he was University of Minnesota’s champion of debate and oratory – to help the German government.

Eric Ostermeier, curator of the Minnesota Historical Election Archives, said Lundeen would have given that pro-Nazi Labor Day speech found among the wreckage of the plane crash “with a lot of flair and what not.”

“He was very confident in his talent as a public speaker,” Ostermeier said.

Lundeen was also enlisted by German agent George Sylvester Viereck, because of his status as a senator and the perks that came with the job. Those included being able to mail out thousands of copies of speeches written by Viereck at taxpayer expense thanks to the Congress’ franking, or paid postage, privileges.

Having succeeded in partnering with Lundeen, Viereck eventually enlisted another two dozen or so U.S. Senate and House members to help him establish a mass-mailing Nazi propaganda effort run out of the U.S. Capitol.

Viereck provided moral and financial support to a range of virulently anti-Semitic and racist organizations across the United States. Maddow’s podcast reveals some of those plots Viereck and Hitler’s government fomented.

For instance, there’s the story of Charles Edward Coughlin, a Catholic priest based in Detroit. Coughlin had a huge following through his popular radio program and was a virulent anti-Semite and defender of the Nazi government.

In Brooklyn, N.Y., members of the Christian Front, a national organization inspired by Coughlin’s broadcasts, planned an armed para-military coup of the U.S. government. Other seditionists blew up weapon plants in the United States, killing and maiming scores of workers.

Attempts to destabilize and even overthrow the U.S. government, as conversely efforts to fight fascism by the Justice Department and ordinary citizens like Los Angeles attorney Leon Lewis, who with his friends infiltrated the American “brownshirt” movements and uncovered violent plots, may soon come to the big screen. Steven Spielberg’s production company, Amblin Entertainment, has recently purchased the movie rights to Maddow’s podcast.

How did a Minnesota senator become a Hitler ally?

There was a natural path that took Lundeen from a progressive Midwestern politician to a key player in Hitler’s propaganda war. It involved Lundeen’s passionate embrace of isolationism.

A South Dakota native who graduated from Carleton College and the University of Minnesota Law School, Lundeen had a passion for politics. He was elected as a Republican to the Minnesota state House and in 1916 to represent a Hennepin County-based district in the House of Representatives.

Lundeen was adamantly opposed to the United States’ involvement in World War I and campaigned on that stance.

“He felt the United States had become a great power because it maintained its independence and wasn’t constrained by alliances,” said Ostermeier.

That isolationist view did not cause much of a stir before the United States entered the war, but Lundeen’s refusal to support the U.S. war effort in any way when America’s young men were fighting overseas eventually did not bode well with Minnesota voters.

“When American troops are actually in combat, virtually every member of Congress, every politician sort of makes a show of supporting the troops and even goes over to visit the trenches of the Western front and things like that,” historian Bradley Hart says in the podcast. “Lundeen doesn’t do any of these things. He, he sort of refuses to support the war effort. At one point he does try to visit the troops and is turned away by the military because he’s seen as a, an almost unpatriotic figure.”

The podcast describes an event in which angry constituents pushed Lundeen into a refrigerated rail car. He was not rescued until the train had traveled for 20 miles down the track.

While Lundeen lost reelection, he did not stop pursuing political office, running for state Legislature, governor, Minnesota Supreme Court chief justice, U.S. Senate and other offices. In the process the perennial candidate switched party allegiances to independent, then became a member of the Minnesota Farmer Labor Party, a precursor to the DFL.

He eventually won a seat in the U.S. House again, as a Farmer Laborite, and was accused by Republican rivals of being a Communist sympathizer for sponsoring the Workers’ Unemployment Insurance Bill and addressing a meeting of “Friends of the Soviet Union” at Madison Square Garden. No matter, in 1936, Lundeen won a special election to the Senate.

Although he switched party affiliations several times, Lundeen remain an isolationist and opposed U.S. involvement in World War II. That high-profile stance drew Viereck’s attention.

Nancy Beck Young, a historian specializing in 20th century American politics at the University of Houston who is featured in the podcast, said Viereck was on the lookout “for members of Congress who were susceptible” to his pitch, which included splitting the money Berlin was paying for the operation.

“There was a quid pro quo on the table,” Young said. “Lundeen wasn’t even doing the bulk of the work, Viereck was writing the speeches.”

Young also said Lundeen was “a dupe and a fool” but wasn’t ready to fall on his sword for the fascists he was helping.

“He was a fine player of the politics of subversion until he discovered the FBI was on to him,” she said.

Having succeeded with Lundeen, Viereck expanded the number of congressional collaborators, which included former Rep. Hamilton Fish, R-N.Y., and former Sen. Burton Wheeler, D-Mont.

These powerful men were able to use their political influence to prod the Justice Department to remove a competent, ambitious prosecutor from investigating Viereck’s operation and the slew of other Nazi-promoted plots to destabilize the U.S. government. The seditious lawmakers said the Justice Department and the FBI were embarked on politically motivated prosecutions.

Meanwhile Lundeen’s widow, Norma, kept up a constant defense of her husband and threatened media outlets with lawsuits if they wrote about the conspiracies.

Right after her husband died in the crash, Norma Lundeen traveled to Washington, D.C. to remove a file that contained all the correspondence between Lundeen and Viereck from her husband’s Capitol Hill office. She later told federal officials the file had been lost in a burglary of her home.

Another Justice Department prosecutor failed to convict the accused seditionists after a wild trial that featured 22 defense attorneys filing thousands of motions and the death of the judge, causing a mistrial. But the prosecutor, John Rogge, went on to collect new information about the conspiracies in Germany after the U.S. military obtained control of Nazi government documents.

Rogge was forbidden from making the new intelligence public, presumably because it contained new information about U.S. lawmakers in the pay of the German government. The podcast said President Harry Truman was involved in that decision.

The information contained in those German files leaked anyway. After Rogge made public appearances to discuss those findings, he was fired. But Rogge’s continued warnings of the fascist threat to the United States had an impact.

“The removal of Hitler and Mussolini and a few of their collaborators does not mean that fascism is dead,” Rogge said in a New York city speech in 1946.

Rogge’s campaign succeeded in a way his attempts to send the seditionists to jail did not. The lawmakers involved with Viereck all lost their seats in their next election.

“The voters exacted their retribution even if the Justice Department did not,” Young said.

She also said that parallels could be drawn between the attempts of Nazi Germany to undermine American democracy and in the 1930s and 1940s and the efforts of Russia and other nations to sow discord in the U.S. political system now.

“It’s pretty stark just how much the events of those times rhymes with what we live through now, and continue to live through,” Young said.

This article originally appeared on St. Cloud Times: How a U.S. Senator from Minnesota became a key player in a Nazi plot