U.S. Virgin Islands cozied up to Jeffrey Epstein. Now they’re profiting from his sex crimes

For two decades, the U.S. Virgin Islands’ most prominent government and elected officials — as well as their pet charities, educational institutions and causes — were paid millions of dollars by Jeffrey Epstein in the form of salaries, campaign contributions and consultant fees.

His most trusted employee was the U.S. territory’s first lady.

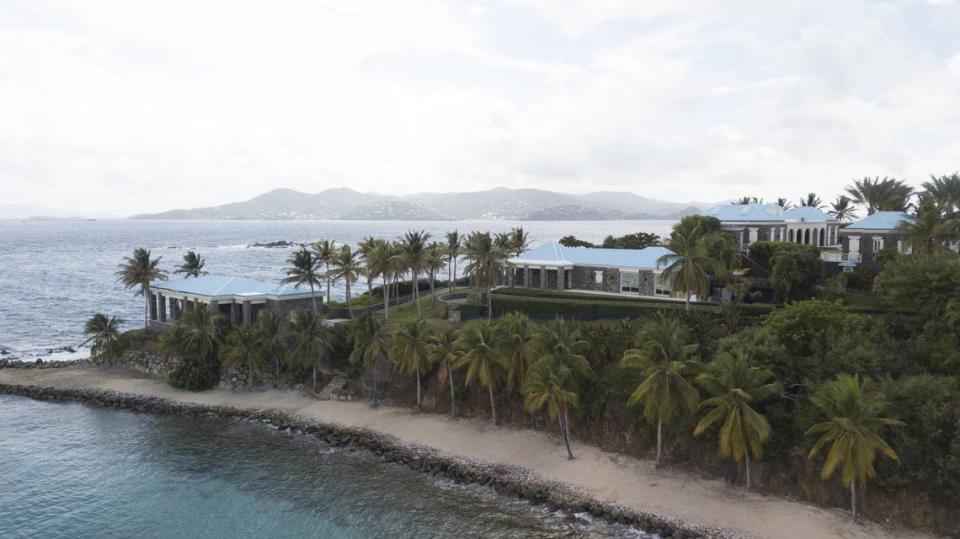

At the same time, USVI authorities paid little mind to the young women and girls he shuttled through the St. Thomas airport following his 2008 Palm Beach conviction for soliciting a minor for sex. Epstein’s abuse of underage girls became so well publicized that his hideaway, an oasis built on a bluff overlooking the Caribbean, became known as Pedophile Island. For years, it was suspected that Epstein’s palatial compound on his private island was being used as a place for wealthy and powerful people to commit sex crimes.

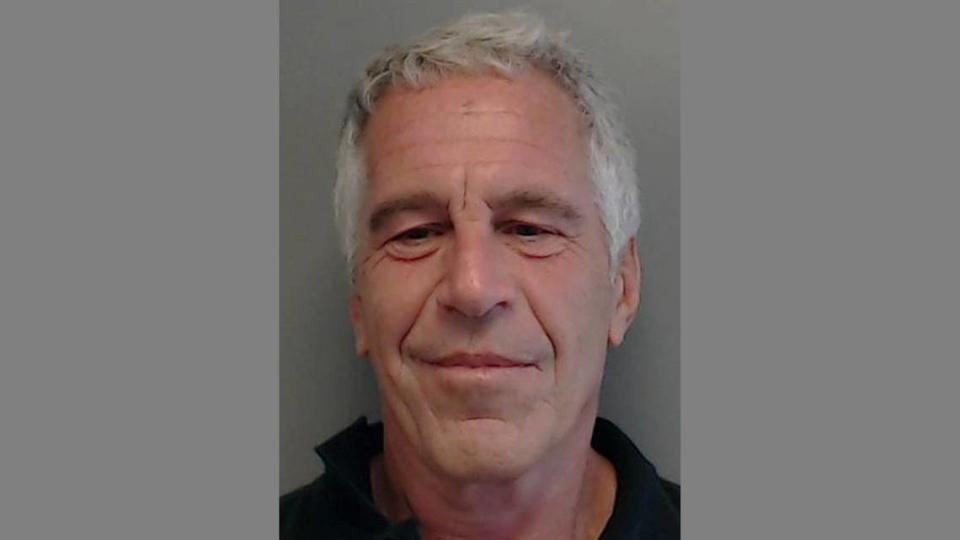

Now, the same USVI government that turned a blind eye to Epstein’s crimes is filing lawsuits and reaping tens of millions of dollars from companies and individuals it claims enabled the serial sex trafficker. Epstein, a New York financier whose friends included leaders in the worlds of finance, government and science, died in a New York prison cell in August 2019 while awaiting trial on federal charges. His death was ruled a suicide by hanging.

In the years since Epstein’s death, a litany of federal lawsuits have been filed, targeting individuals, banks and business executives in Epstein’s circle who have been accused of facilitating or being complicit in his sex-trafficking operation. At least 200 victims have said he and his associates sexually abused them as girls or young women over two decades.

As a result, about $500 million in legal settlements have been paid to Epstein’s survivors, most of that from Epstein’s estate — and from JPMorgan and Deutsche Bank, the two financial institutions where he conducted millions of dollars in financial transactions that should have raised red flags.

Yet no single entity potentially stands to collect more money in the fallout from Epstein’s crimes than the government of the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Thus far, the USVI has collected just shy of $200 million in Epstein-related settlements, most of it the result of a civil racketeering lawsuit its former attorney general filed against his estate. Now it is seeking another $190 million in an epic lawsuit filed against JPMorgan.

USVI and JPMorgan both claim the other ignored evidence of — and even profited from — Epstein’s sex trafficking. But while much of the spotlight has been on the financial institutions that continued to do business with him, very little attention has been given to the role that the government of the USVI — a territory of the United States that has far-reaching law enforcement powers — played in helping one of the most notorious sex traffickers in U.S. history.

The USVI governor, Albert Bryan Jr., declined to comment on JP Morgan’s allegations, but a spokeswoman for the territory’s Department of Justice said that JP Morgan “is the only party to this lawsuit that had intricate knowledge of Jeffery Epstein’s criminal operation.”

The USVI Department of Justice spokeswoman, Venetia Velazquez, added: “We see the lengths JPMorgan has gone to in order to dodge accountability and distract the public from that critical fact. It is extremely unfortunate that, while JPMorgan continues to display considerable vigilance in attempting to shape its self-serving narrative and rebuild its reputation in the press, it showed no similar concern for protecting the lives of the young women and girls who were preyed upon.”

Said JPMorgan in a statement: “Rather than account for its own failures to investigate and monitor this criminal under its jurisdiction and to protect its citizens and sovereign interests, USVI blames a third-party bank that did not have USVI’s authority to enforce any law.”

In recent months, discovery from the federal civil lawsuit provides the strongest evidence to date of Epstein’s influence in the USVI and his cozy relationships with three of the territory’s governors, its former first lady, attorney generals, senators, leaders of its Economic Development Commission, the Virgin Islands police, federal marshals, the Port Authority and the territory’s representative to Congress.

Epstein even gave free turkeys to 78 federal Customs agents at the St. Thomas airport for Thanksgiving.

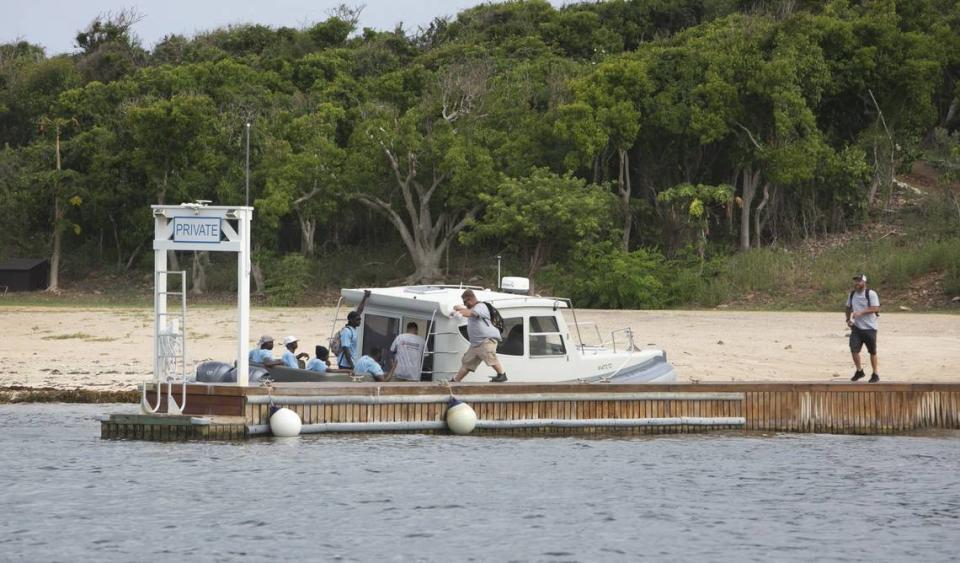

At least since 2005, the FBI suspected that Epstein was trafficking girls and women to and from several of his residences — including his waterfront home in Palm Beach and his sprawling USVI estate. The island — surrounded by treacherous sea urchins, accessible only by helicopter or boat — provided a perfect cover for the sexual abuse that victims have long alleged happened there.

A U.S. Justice Department investigation completed in 2019 revealed that at least since 2007 FBI agents and federal prosecutors were concerned about Epstein’s USVI activities, fearing that he was abusing victims on his island retreat.

In 2020, Denise George, the USVI’s then-attorney general, finally acknowledged what had been rumored for two decades: that Epstein’s island was a nexus for his sex trafficking operation. George filed a racketeering lawsuit against Epstein’s estate, alleging that he would transport girls there as young as 11 and 12, keeping a computerized database to track the girls’ whereabouts. Several victims have also said Epstein’s assistants would seize their passports.

The USVI government, in addition to the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, was responsible for monitoring Epstein’s movements in the territory after his release from the Palm Beach County jail in 2009. As part of a plea deal, Epstein served just 18 months in the county jail for procuring a minor for prostitution and felony solicitation — and was required to register as a convicted sex offender.

Epstein changed his primary residence to Little Saint James, his 72-acre private resort that included a helipad, private dock, gas station, high-capacity water filtration, two swimming pools, four guest villas, three private beaches, a gym, and other buildings. This placed him under the territory’s law enforcement jurisdiction and supervision. It’s unclear how often he was required to register in person over the years, but USVI officials who gave statements for the JPMorgan lawsuit could find records of only five visits by U.S. marshals and the territory’s officials between 2010 and 2019.

USVI officials also admit they took no steps to ensure that Epstein wasn’t continuing to harm minors at a time when authorities in New York, where he owned what was reputed to be Manhattan’s largest private residence, had classified him as a tier 3 sex offender — one that is at a high risk of continuing to prey on young women and girls.

JPMorgan has filed hundreds of court exhibits, emails and depositions in an effort to prove that there was “a decades-long quid pro quo between Epstein and the USVI government.” Epstein was rewarded, according to JPMorgan, for his largess with $300 million in tax breaks that USVI authorities extended year after year — even though audits showed he often fell short of the program’s regulatory requirements.

JPMorgan lawyers described his office manager, former USVI first lady Cecile de Jongh, as Esptein’s “primary conduit,” assisting him in obtaining special benefits, including visas to bring young girls from other countries to the island.

Since at least 2000, including during the time her husband John de Jongh was governor, Cecile de Jongh worked for Epstein, earning a $200,000 annual salary plus other perks, including private school and college tuition for the couple’s children.

John de Jongh declined to comment for this story. The Miami Herald was unsuccessful in reaching his wife. They have not spoken publicly about the allegations contained in the lawsuit, or about their relationship with Epstein.

But in a May court deposition, Cecile de Jongh testified she had no reason to suspect that Epstein was doing anything other than being “helpful” to young women.

“This is a person who had one offense, had to register as a sex offender. Didn’t see him with — anybody underage, or anything. And I’m thinking he is just trying to be helpful to people,’’ she said during the deposition.

She also said she confronted Epstein about his 2008 sentence for soliciting a minor for prostitution in Florida. “I basically asked him what was going on…what the hell was going on. And he said, ‘I — it was an error in judgment.’ And I said ‘so that’s it, you approached somebody who you thought was older?’ And he said yes.”

She recalled that he assured her it would never happen again.

“I learned my lesson,” she said he told her.

The first lady’s role, however, went far deeper than being an office manager, according to the lawsuit. She told him who to hire and who to fire. She helped him navigate the island’s political landscape. She told Epstein where to spend his money. And, according to the lawsuit, she helped him get visas to freely transport women to the island.

In one instance cited in the lawsuit, Cecile de Jongh arranged for three young women from Europe to get student visas to enroll in a class at the University of the Virgin Islands.

“Ultimately [the university] structured a bespoke class to enroll victims and provide cover for their presence in the territory — the same year Epstein donated $20,000 to the university through one of his companies,” JP Morgan said in a court filing.

Cecile de Jongh also steered Epstein’s money to her husband’s preferred candidates, according to the lawsuit.

In 2014 — when her husband was still in office — she wrote to Epstein about a political contribution he had given to the campaign of Kenneth Mapp, who was running to succeed her husband as governor.

“The Mapp campaign is going to take the $ that you gave to attack John. …can we stop payment on the check to send a message?” she said, according to the lawsuit.

In 2016, Epstein emailed Cecile asking her, “How did our candidates do?” She replied that they had all won their races. Emails also show that she directed that payments from Epstein’s companies be made to political action committees that benefited candidates. In 2018, she directed another Epstein employee to “cut a check” for $25,000 to a PAC named “Islands Engaged Inc.,” according to the suit.

The former first lady also went to great lengths to help Epstein get special privileges as a sex offender. Emails contained in exhibits with the case show she worked with lawmakers to water down a new and more restrictive sex offender law in 2011. She showed Epstein a draft of the law, writing “Will this work for you?”

He and his lawyers suggested changes that would give him more freedom. While Epstein’s changes were eventually dropped from the law, officials nevertheless worked on finding a loophole for Epstein, according to the lawsuit. Cecile promised she would continue to influence lawmakers — as well as her husband’s attorney general, Vincent Frazer.

“We will figure something out by coming up with a game plan to get around these obstacles,” she wrote in July 2012, adding later “We will work with Vincent to give the discretion for status quo for you — that’s the least he can do.” Frazer ultimately issued a waiver that allowed Epstein to travel with fewer restrictions.

After the publication of the Miami Herald’s series “Perversion of Justice” in late 2018, the territory’s assistant attorney general, Carol Thomas Jacobs, rescinded Epstein’s sex offender waivers, according to the lawsuit. Denise George, who was then attorney general, testified in a deposition for the lawsuit that the territory’s current governor, Albert Bryan Jr., tried to pressure her to reinstate the waivers, which she said made her uncomfortable.

“Not every sexual offender or any person, you know, are in the position to have the governor make the request to the attorney general…that by itself indicated to me that [Epstein] was flexing his political influence over or with the governor…” George said, in a deposition she gave as part of the JPMorgan lawsuit.

In 2022, George obtained a $105 million cash settlement in the racketeering lawsuit she filed against Epstein’s estate. On Dec. 27 that same year, she filed the $190 million lawsuit against JPMorgan — and was promptly fired by the governor days later, on New Year’s Eve. Bryan did not provide a reason for the dismissal, but people who were briefed on the matter said Bryan was angry George filed the lawsuit without consulting him. The people briefed on the matter, who were not authorized to speak publicly, said the governor was likely concerned that the USVI’s own failures to monitor Epstein would come out as part of the lawsuit.

Bryan, elected in 2018, previously served as chairman of the Economic Development Commission and was a member of that commission when Epstein was awarded his lucrative tax breaks.

According to the lawsuit, Epstein was asked to give $25,000 toward Bryan’s inauguration and $30,000 at Bryan’s direction to the USVI’s Little League.

In June, Bryan was also deposed as part of the JPMorgan lawsuit. He indicated he was not concerned about Epstein’s history, referring to the 14-year-old girl Epstein admitted abusing in the 2005 Florida case as a “hooker.” He also acknowledged that, based on the information he had at the time, he “really wasn’t interested” in any of the allegations that surfaced about Epstein trafficking women and children on the island.

Through a spokesman, Bryan apologized for the remark.

“I believe that we should honor and support all victims of human trafficking. That was a terrible use of language, and I should never had said that. It was disrespectful,” the governor said in a statement.

He declined to answer questions about why his administration gave a well-known convicted sex offender such leeway for so many years.

Omerta

JPMorgan alleges that USVI officials’ failure to investigate Epstein reflects the omerta-like culture — the code of silence reminiscent of a crime family — that the territory’s politicians had during the time that Epstein lived there and ran his businesses from an office complex in the Red Hook quarter of St. Thomas.

To prove their case, JPMorgan’s attorneys deposed a number of former and current USVI elected officials, including John de Jongh, the former governor.

“Did you direct anyone on your staff to do any kind of an investigation into Epstein?” one of JPMorgan’s lawyers asked during a deposition.

“I would not do that,” de Jongh replied.

“Why not?”

“My assumption will be that the Department of Justice, any of the entities dealing with Jeffrey Epstein, would have done that,” de Jongh replied.

He acknowledged he never checked or asked anyone in his administration — including his own attorney general — to check on the territory’s most infamous sex offender.

Frazer, attorney general for the USVI from 2007-2015, said in a deposition that he had the ability to investigate who Epstein was bringing into the St. Thomas airport on his private jet but didn’t believe he had any reason to do so.

“Who [sic] may have flew in with him on his private jet, the government of the Virgin Islands officials would not know,” Frazer said.

In fact, nearly all of the USVI officials interviewed as part of the lawsuit acknowledged that they saw news reports about Epstein’s abuse of underage girls, but said they dismissed the stories as sensational rumors. JPMorgan’s documents show that no one in USVI law enforcement considered investigating Epstein — even though many of the news stories during this time were based on federal lawsuits containing sworn affidavits by almost two dozen girls alleging Epstein had molested them.

One victim who did fly on Epstein’s plane to his island, Sarah Ransome, said she is angry that no one — including the USVI’s attorney general, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol as well as the FBI — ever did anything to stop Epstein.

Ransome was 22 when she was lured to the island in 2006 for what she thought would be a social gathering. Born in South Africa, Ransome hoped to study fashion in New York. Epstein told her he had connections at the Fashion Institute of Technology and would help her achieve her dream. Instead, she said, she was raped by Epstein dozens of times over the course of a year. In an interview with the Herald, Ransome said that Epstein had carte blanche in the USVI. Only once did she recall an official scrutinizing her passport — and that was when she was arriving on a commercial plane.

She doesn’t remember anyone ever checking her passport or belongings when she arrived on Epstein’s private jet. His passengers always deplaned and went directly to a helicopter or a boat for the trip to St. James, where they were greeted by a cheerful staff that she said seemed to normalize the promiscuity and sexual activity that happened on the island.

“Where was the FBI?” Ransome said. “I was being trafficked while the FBI was investigating him. They could have picked up the phone and called to find out what was going on.”

Ransome, who is suing the FBI for its failure to stop Epstein, said it’s clear the USVI also looked the other way for years and, as a result, she and other victims continued to be sexually abused. The government should not be rewarded for its complicity, she said.

“How dare the USVI — which allowed hundreds of women to be trafficked — how dare they profit from what happened.”

WINDFALL

Thus far, the USVI has collected $105 million in a cash settlement with Epstein’s estate, $30 million from the sale of Epstein’s islands; and another $62.5 million in cash from Epstein client and private equity investor Leon Black who denied any wrongdoing while paying the settlement. It is seeking another $190 million from JPMorgan.

Government officials say the proceeds will benefit the territory’s victims of sexual abuse, to prevent human trafficking and investigate sex crimes. But critics point out that oversight of the fund could be problematic in a territory with a history of public corruption.

Marci Hamilton, executive director of Child USA, a think tank fighting for the civil rights of children, has been working with USVI officials to help set up the territory’s anti-trafficking initiatives. She said the money that the government has received from Epstein-related settlements will be used to launch training programs for law enforcement, childcare workers and education and health professionals.

“It’s sex tourism,” Hamilton said. “We see it in Thailand and the Philippines, but it’s also here in the Caribbean. Because it’s part of tourism and because it’s their primary income — it is almost a cancer.”

The USVI’s “Victims of Human Trafficking Prevention Act” has mandatory reporting requirements as well as extensive services for trafficking victims.

“I look at the USVI as laying down the gauntlet and saying ‘no more.’ This is one of the most progressive laws on sex trafficking in the nation,” Hamilton said.

The legal settlements are nevertheless a windfall for a country that faces serious economic and financial challenges. A recent bond report noted that the Epstein settlement would “temporarily alleviate the government’s financial distress.” The U.S. Government Accountability Office recently cited the USVI’s debt and “weak financial management practices” as factors in its financial instability.

The territory also has a history of corruption involving misspent public funds.

In 2013, former USVI Senator Alvin Williams pleaded guilty to federal racketeering charges involving bribery of an USVI official and for soliciting bribes from numerous developers, and using his tax-supported staff for his personal use. In 2018, another former senator, Wayne A.G. James, was convicted of stealing tens of thousands of taxpayer dollars he received to fund a “historical research project” that was actually used to pay his own campaign and personal expenses.

The former governor, de Jongh, was arrested in 2015 on charges of embezzling $500,000 in public money to make improvements to his private home.

Emails from the USVI lawsuit against JPMorgan show Epstein offered to help de Jongh by loaning him money and offering “suggestions” to the prosecutor in the case.

“I will play any role in this you guys like,” wrote Epstein. “I can lend John the money so he immediatly [sic] has it. I would gladly be on the phone (anonymouse[sic]) with …. the prosecutor offering suggestions.”

In one of the JPMorgan court filings, de Jongh, on Dec. 27, 2015, emailed Epstein, asking for a loan to help pay the settlement.

“Per our previous conversation,” de Jongh wrote, “I would like to take you up on your offer and request to borrow $215k. I really appreciate your willingness to help.”

The criminal case against de Jongh, who denied any wrongdoing, was subsequently dropped after he paid a settlement of $380,000.

JPMorgan alleges that some of USVI’s most veteran lawmakers were heavily influenced by Epstein’s money. Among those named in a subpoena for the JPMorgan lawsuit is Celestino A. White Sr., an 11-term senator in the USVI legislature who is also a member of the board that oversees the airport. Emails included in the lawsuit discovery show that White’s “consulting and management firm” sent Epstein a contract for unexplained services for his island.

“Senator White signed the contractor’s agreement and the confidentiality agreement …we will need to get him a check for $10,000 by Friday,” Cecile de Jongh wrote to Epstein.

“Approved.” Epstein wrote back.

In 2015, Cecile de Jongh suggested to Epstein: “You may want to consider putting Celestino on some sort of monthly retainer. That is what will get you his loyalty and access.”

The Herald was unsuccessful in reaching White. There is no indication in the lawsuit whether he was ever placed on a retainer by Epstein.

As for the USVI’s airport authority and the federal marshals, Epstein had friendly relations there too, emails show.

In 2010, Epstein wrote in an email to Cecile de Jongh, complaining that he was having difficulty with an official from the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol at Cyril E. King Airport on St. Thomas, where Epstein’s pilots would fly in and out on his private jet. Emails indicate that Epstein knew some of them personally.

“Who is in charge of customs in the v.i.? I used to have a great relationship with gloria lambert, the airport supervisor. I would like to know who is now in her place, or her boss,” Epstein wrote to Cecile de Jongh, referring to a customs official at the airport.

De Jongh promised a call would be made to the head of Customs.

Lambert, now retired, told the Miami Herald that she was under the impression that the young women who accompanied Epstein were models. She didn’t suspect any of them were being trafficked — or were underage.

“If I was aware I would have taken the initiative, but there was nothing suspicious when I dealt with Mr. Epstein and his passengers,” Lambert said.

In another email, Cecil de Jongh solicited Epstein’s support for her husband’s proposed appointee to the Virgin Islands Port Authority, which controls the airport.

He “worked his tail off on the campaign,” she wrote of the nominee.

Epstein gave other perks to former Gov. de Jongh and his wife, including paying hundreds of thousands of dollars in private grade school and college tuition for their children, according to the lawsuit discovery documents. In 2010, for instance, Cecile became irate when Epstein failed to pay a $25,000 bill — tuition for one year for one of her children.

“I will need to negotiate a raise so that I can afford to pay for my children’s tuition at college,” the first lady wrote to Epstein. “John and I have put money into the campaign based on what we thought was going to happen with the tuition payments…my oldest is a senior this year and I do not want him or my daughter to be asked to leave school this semester.”

PLASKETT

In June 2014, Cecile de Jongh asked Epstein to help an up-and-coming political star, Stacey Plaskett, get elected as a delegate to Congress representing the USVI.

Plaskett’s parents were born in St. Croix, USVI, but moved to Brooklyn, New York, where Plaskett was born and attended Choate Rosemary Hall as a boarding student. After graduating from Georgetown University and American University law school, she became a Republican assistant district attorney in the Bronx. She then worked as an attorney for the U.S. House Ethics Committee and later as a lawyer in the Justice Department. In 2007, she moved to the Virgin Islands and worked in private practice before turning her attention to running for office, changing her party affiliation to Democrat in 2014.

“She needs to raise about $75,000 between now and August,” Cecile de Jongh wrote in an email to Epstein. “Do you think any of your friends would give to her campaign?”

Plaskett already knew of Epstein, as she had been the attorney on the USVI’s Economic Development Commission at the time that Epstein’s tax breaks were approved, then worked for Epstein’s longtime USVI attorney, Erika Kellerhals.

In a deposition given in May in the USVI lawsuit, Plaskett said she didn’t recall whether she did any legal work for Epstein or his companies while working for Kellerhals, although she acknowledged that Epstein was a client of the firm at the time.

From 2014 until 2018, Epstein and his business associates donated a little over $30,000 to Plaskett’s campaigns, she confirmed during the deposition. She also acknowledged that she visited Epstein’s Manhattan mansion as recently as 2018 in a bid to get him to contribute money to the Democratic Party. Epstein offered what she asked for — again, $30,000 — but the Democratic National Committee ultimately rejected the contribution.

Plaskett was asked why the DNC had declined Epstein’s donation.

“He had not passed their vetting,” Plaskett replied.

“What did you understand that to be a reference to?” the JPMorgan lawyer asked.

“I did not know the specifics of what that vetting was,” Plaskett said.

She was then asked whether that caused her to rethink taking contributions from Epstein.

“I recall thinking if I should continue receiving contributions from him,” she replied according to the transcript.

For years, Plaskett resisted returning Epstein’s donations. She reasoned that his felony sex charges in Palm Beach had nothing to do with the money he earned through his company. But after Epstein’s 2019 arrest by the FBI, she faced even more scrutiny about her connections to Epstein. She eventually relented and said she would donate the money to support USVI organizations that help women and children.

The Herald tried to get details to confirm the donations and the amounts, but Plaskett’s office did not respond to multiple inquiries.

This article has been updated with a statement from the U.S. Virgin Islands’ Department of Justice and to note that Celestino A. White Sr. is a member of the commission overseeing the St. Thomas airport, not its chairwoman.