UA professors recreate sights and sounds of Notre Dame Cathedral

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A major grant obtained from the National Endowment for the Humanities will enable four University of Alabama professors to recreate the environment a worshipper in the Middle Ages might have experienced inside the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

The cathedral was heavily damaged in a fire in 2019. Almost from the moment the ashes cooled, researchers have been working to understand the ancient and majestic gothic structure and to restore it to its pre-fire majesty.

More: 'MasterChef' adventure over, Gadsden's Savannah Miles now seeks legal career

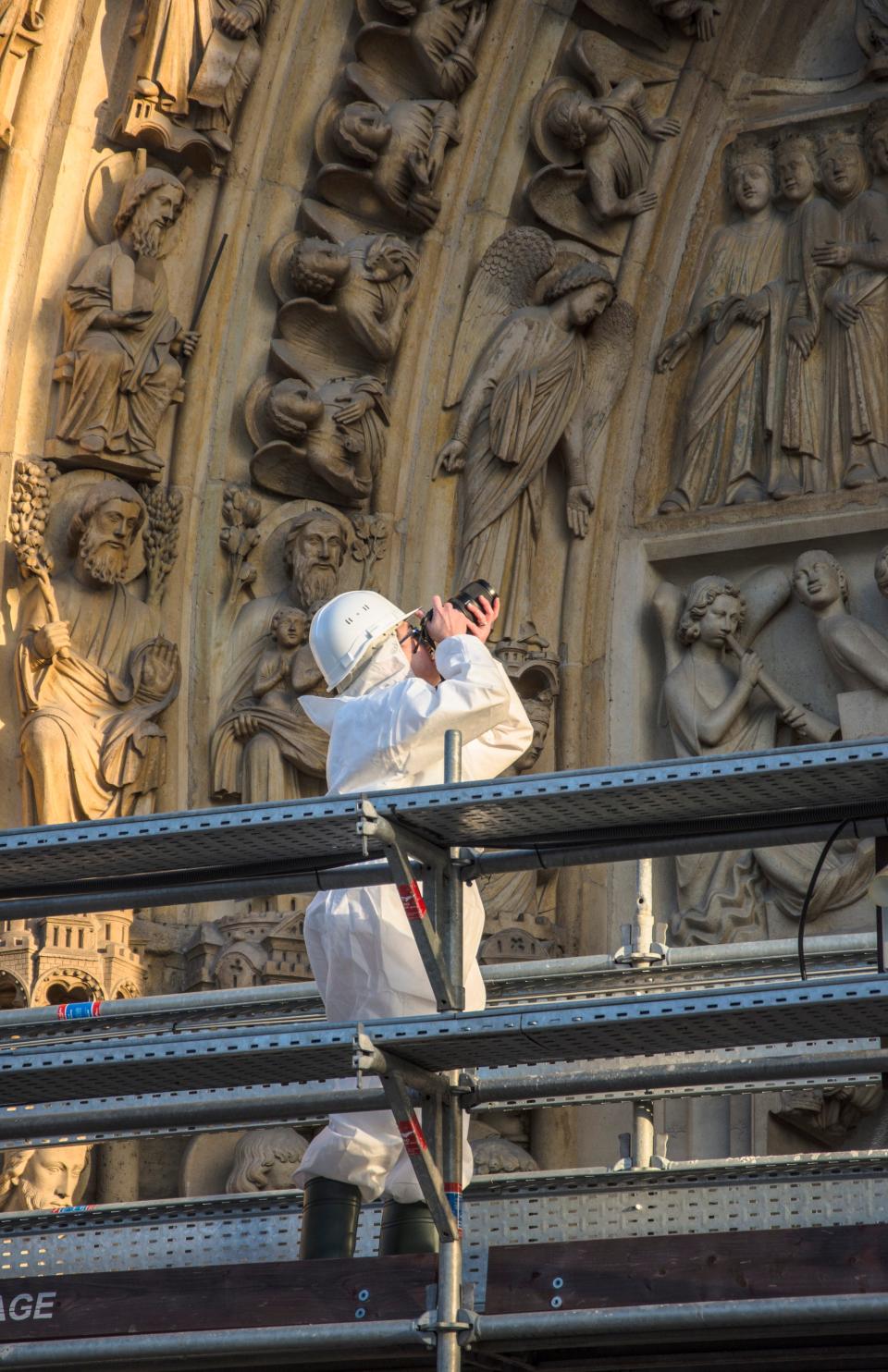

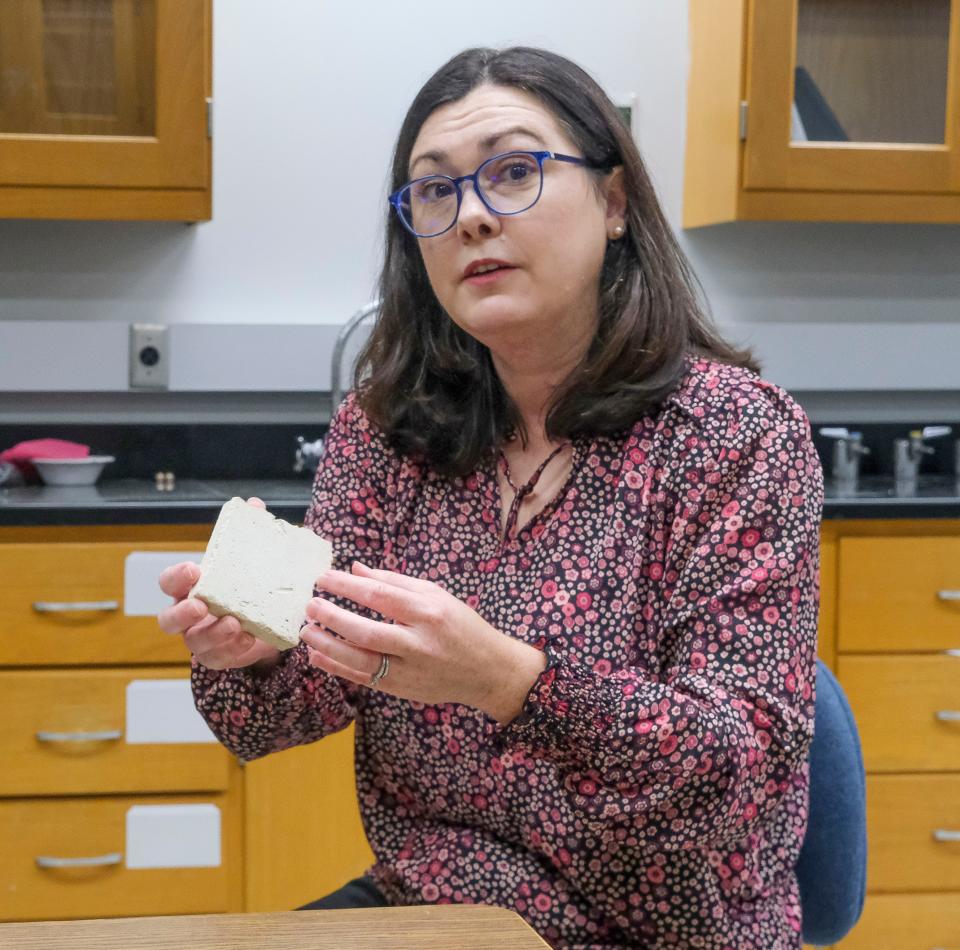

Jennifer Feltman, an associate professor of art history at UA has worked as part of an international team studying the statues and carvings on the cathedral's western facade. She is advancing that work through the NEH grant and is drawing in other professors from other academic disciplines to collaborate.

"It’s the first time that UA has received a Level III collaborative research grant (from NEH). It is about working across disciplines to address a complex problem that addresses some aspects of the humanities. What we are really doing is bringing together the arts and sciences to solve a unique question from multiple angles," Feltman said.

The grant is for $249,995 and is one of the largest NEH grants ever awarded to the University of Alabama.

Recreating the Notre Dame experience

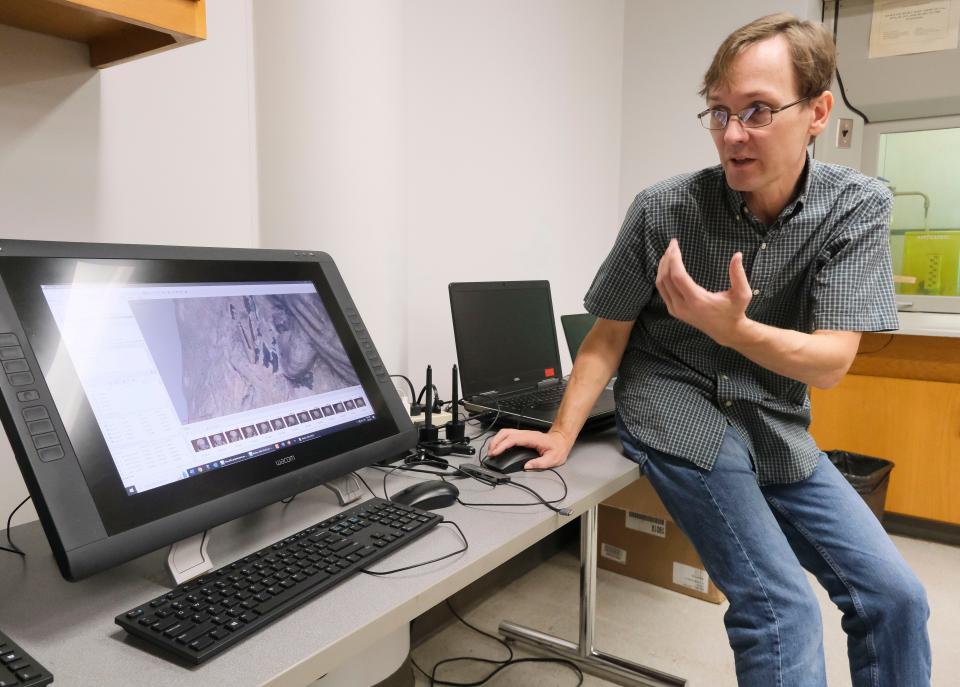

Feltman and colleagues Jennifer Roth-Burnette, Alexandre Tokovinine and Jeremiah Stager are combining their areas of study. Roth-Burnette studies medieval chant and polyphony, Tokovinine is an associate professor in the department of anthropology, and Stager is a cultural resources assistant in the Office of Archaeological Research.

Their efforts will produce a project, "Notre Dame in Color: Interpreting the Layers of Polychromy on the Sculptures of the Cathedral of Paris Using 3D Modeling." Both Tokovinine and Stager are 3D specialists.

By combining their various disciplines into one study, the professors hope to create an immersive representation of what it would have been like for a worshipper in medieval times to participate in a religious service at Notre Dame. A major part of gaining that understanding is to evaluate how colors were used in the worship experience.

Originally, many of the sculptures at Notre Dame Cathedral were painted. Over the years they were frequently repainted. The changing use of color in worship is a key to understanding the history of the building as well as understanding the people who worshipped there.

"The sculptures in the Cathedral of Notre Dame were painted in multiple layers. We know that some have as many as 16 layers, most have between three to five layers," Feltman said. "Layers of colors were added to the stones. We have about 99 samples from the whole of the west facade that shows stratigraphy. Think of it like archaeological layers of paint or maybe you have painted the walls in your kitchen multiple times. It’s kind of the same thing."

The colors used were not simply reflected in the painting done on the sculptures but were also reflected in the vestments worn by the priests, the color of light coming through the stained glass windows and the colors mentioned in the chants, which were a regular part of worship. All of these interpretations of color in worship tell the researchers a story of how people throughout the history of the cathedral understood God.

Roth-Burnette's study of colors in plainchants, part of the liturgy that was sung in worship services, show how even the music of the day was used to convey ideas about God. Worshippers in Notre Dame experienced a worship service filled with color, light and sound that was a product of the architecture of the building as well as its art, music and liturgy.

"Plainchant is an interesting space for that because in the community of people who worshipped at the cathedral, it wasn’t just church on Sunday like we do now. It was church all day, every day, and so most of the words, the voices that would be projected inside the worship space were plainchant, they were sung. The words sung to those melodies include ways of thinking and ways of explaining the world and ways of understanding God," Roth-Burnette said.

The exploration of plainchant delves into the colors mentioned, since they are representative of certain aspects of the culture's perception of God.

"There is a chant that mentions the birth of Jesus and it talks about how he came with a purple stole around his neck. That idea of a purple stole is also shown in some of the artwork of the time and it shows Jesus rising from the dead wearing that purple stole, so it is likely a symbol of life and a symbol of his royal status, which was derived from his parentage as well as from God. We can actually trace mentions of the color purple in the chant and see something deeper about how the community at the time understood their God," Roth-Burnette said.

Tokovinine, who specializes in the Mayan culture, sees many aspects of color that tie his work in the Americas with the culture of Europe.

"One of the reasons I am interested in this project is because I published on pre-Columbian use of color. There is this moment where the two cultures actually meet. They both have rich symbolism of color. Then they translate each other as we try to reimagine significance of color."

The cultural and linguistic differences between Europe and the Americas cause changes in the way the Mayan culture expressed itself relative to the Europeans, but the idea that color was important in their worship is clear to Tokovinine.

"Mayan people translate Christian doctrine and sermons and then they translate certain terms into Spanish. So when they wanted to say 'glorious Mary,' they don’t say that, they say 'green blue Mary, yellow Mary.' So it is kind of fascinating," Tokovinine said.

He also brings 3D modeling, which he uses extensively in his study of the Mayan people, to the project. Using scans of sculptures, he creates a digital framework on which colors and textures can be layered and studied. These interactions of texture and color are Stager's specialty.

In his work with 3D modeling and texturing, he is able to explore how the colors would have appeared to those worshipping in ancient times. Stager began his work in 3D modeling by reconstructing elements of the Native American Hopewell culture in Ohio. After moving to Alabama, he applied that technology to company towns that were constructed near the dams that were built in the state in the 1920s. Lighting and texture play major roles in his studies.

"There’s so much that goes into a layer of paint. We don’t even realize it. One of the things I ran into when I started doing 3D models of original buildings, is we don’t realize how much we see," Stager said. "With textures, if you look at this table, if it was brand new, it would be easier to apply a texture. But now there are scratches in it, layers of dust, there’s a lot of things going on that we don’t realize we see, imperfections in the textures."

A multi-sensory environment

Working together, the professors will create what Feltman calls a multi-sensory environment that includes sound, texture, light and color.

"One of the things I think is so exciting about this is that I grew up being fascinated by history, being able to read about and maybe see pictures of buildings that still exist and the way they exist now. By being able to recreate color, and texture, and shape, and all of these elements we are inviting a current audience into that multi-sensory space. It is a way of doing history that allows people to actually enter in on some level to the way it was," Roth-Burnette said.

Feltman said the team wants to convey the awe and wonder a person would feel when walking into Notre Dame. It is an important touchstone for modern people to experience the way their ancestors interacted with their environment.

"We know the world through our five senses. It’s how we engage with it. When I am teaching students, if they are just hearing me say words and maybe reading a book or something on their phone, they are missing the larger effect or feeling of being in the moment. It’s a mixture of scale, walking into a massive gothic cathedral, even having to crane your neck to look at some of these sculptures. Feeling that sense, also that gives you a sense of awe and it speaks to something about the divine that I’m sure they were interested in in the Middle Ages," Feltman said.

When the project is complete, it will be viewable at www.notredameincolor.org, which is hosted by the Alabama Digital Humanities Center. It will reveal the various ways the statues in Notre Dame were painted and repainted over time, giving viewers a feeling for what it was like to be in the cathedral at various times throughout its history.

Gary Cosby Jr. is the photo editor of The Tuscaloosa News. Readers can email him at gary.cosby@tuscaloosanews.com.

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: UA professors recreate Notre Dame Cathedral's original colors, sounds