UA student aims to prevent opioid deaths in Greek life community, one Narcan kit at a time

Armed with a drill, a toolbox and a Narcan kit, Aidan Pettit-Miller enters the Phi Gamma Delta chapter room on a Saturday morning and gets to work.

Over the light buzz of friendly chatter among the fraternity brothers, Pettit-Miller’s drill whirs as it bores screws into the drywall. After a few minutes, the installation of the Narcan kit is complete.

Satisfied with his handiwork, Pettit-Miller waves goodbye to the FIJI brothers as he heads back to his Ford F-150. He hops in the driver’s seat, starts the engine and it’s on to the next frat house on Greek row.

Pettit-Miller, 23, is a senior public health student at the University of Arizona tackling Arizona’s opioid crisis head-on, one fraternity house at a time. Entirely on his own, he started an initiative to install Narcan kits inside all of the fraternity houses on the UA main campus in Tucson. And he has installed all of them by hand.

Naloxone, more commonly referred to as Narcan, is an intranasally administered medicine that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose. Narcan is commonly carried by police officers and emergency medical personnel and is often used in situations where someone is exhibiting symptoms of narcotic poisoning.

After hearing about an accidental opioid poisoning death of a 20-year-old college student at Arizona State University in 2020, reportedly from a Xanax tablet that was laced with fentanyl, Pettit-Miller was able to grasp the severity of the opioid epidemic.

“It was a big wake-up call... fentanyl wasn’t on our campus, but it was on a campus an hour and thirty minutes away,” Pettit-Miller said to The Arizona Republic.

In 2021, Arizona reported 2,015 deaths that resulted from an opioid overdose, according to statistics from the Arizona Department of Health Services. In Pima County alone, over 240 opioid overdose deaths have been reported so far in 2022, along with 458 non-fatal opioid overdose events reported by the department. In these non-fatal overdose events, AZDHS reported that naloxone was administered in 87.2% of these incidents in Pima County — a vast majority of which were administered by Emergency Medical Services personnel.

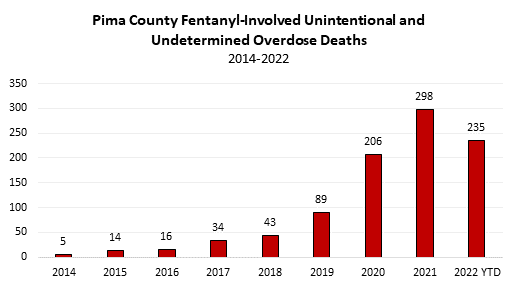

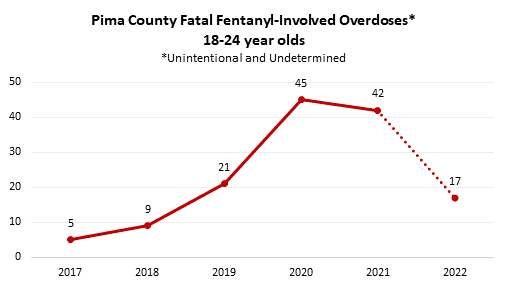

Statistics from the Pima County Health Department detailed that fentanyl-involved overdose deaths have dramatically increased in the past few years, with five deaths recorded in 2014 rising to 298 recorded deaths in 2021. Among the age demographic of 18-24 years, deaths have risen from five in 2017 to 42 in 2021. So far in 2022, Pima County recorded 235 deaths as a result from fentanyl-involved overdoses, with 17 attributed to the 18-24 age range.

A call to action

The implementation of Narcan is critical in a life-or-death situation, as Pettit-Miller experienced personally. Around six months after he heard about the ASU student’s death from fentanyl poisoning, Pettit-Miller was skateboarding at the Santa Rita Skatepark in Tucson when he witnessed a man overdose in the bathroom.

After calling the police for assistance, Pettit-Miller stayed with the man until authorities arrived, where he was able to see the curative effects of naloxone firsthand.

“I sat with this guy for 5 minutes, and I was fully convinced this man was dead,” Pettit-Miller said. “It seemed like (the police officer) just brought this guy back to life.”

Inspired by the remedying effects of the drug, Pettit-Miller became a certified Emergency Medical Technician, where he learned by administering Narcan to several people who were experiencing narcotic poisoning.

Once he started his final semester as an undergraduate, Pettit-Miller decided it was time to take action in his community on campus. Not knowing where to start, he thought about where the highest risk for someone to overdose would be. He concluded that it would be best to start with fraternities.

“They have the most amount of drugs, the most amount of alcohol, the most amount of partying and that’s life, it’s college life,” Pettit-Miller said. “But that’s the area where you would think you probably want to target first.”

As an intern for the Pima County Health Department’s Community Mental Health and Addiction unit, he reached out to his superior, special staff assistant Kimberly Wang who runs Narcan distribution for the county. Wang agreed to provide Pettit-Miller with enough Narcan kits to be installed inside every Interfraternity Council-recognized house on campus.

Building organic relationships:Tucson mom creates social group for those with special needs

“One of the things I would like to highlight is that this project led by Aidan was very student-run,” Wang said. “It was a grassroots approach, and a lot of the agencies that you see here and a lot of the very impactful work, it really starts with the people in the community. So Aidan kind of helped rally everyone together to understand this issue and carried it in carrying the messaging too.”

The university considers fraternity and sorority houses off-campus, according to Marcos Guzman, assistant dean of students and director of Fraternity and Sorority Programs. Guzman said the university did not assist in the initiative, as the facilities are privately owned and operated separately from the school.

Educating the campus community

Mark Person, the program manager for the Pima County CMHA unit, highlighted the importance of not only providing access to Narcan on campus but also educating the community about how prevalent the crisis is among younger people.

“We expressed an interest to get naloxone on campus because of how, especially, young adults are affected by opioid use and overdose rates,” Person said. “And knowing that there’s a huge student population in one small area, it really is a priority for us to try to get some education out there at least.”

After installing Narcan kits inside all of the fraternity houses, Pettit-Miller wanted to make sure that the Greek life community could also be educated about how to use Narcan and the severity of the opioid crisis, so he called upon members of UA’s EMS team to help provide training to fraternity members. Logan McGoldrick-Ruth, a 21-year-old physiology student at UA, is a supervisor EMT with the UA EMS team, and worked with Pettit-Miller in educating people in the use of Narcan.

McGoldrick-Ruth said that members of the UA EMS team split into pairs and gave talks to fraternities during their Monday chapter meetings, explaining what drugs could bring about narcotic poisoning and how different drugs could be laced with opioids.

Pettit-Miller wanted to ensure that fraternity members received this information from someone their own age, in order to make the information more approachable to college students.

“The whole goal of this program is to enable some kid at 3 o’clock in the morning to feel confident enough to bust open that kit and give it to his friend,” Pettit-Miller said. “And I think a big part of it is having another kid come in and be like, ‘Hey, if I can do this, you can do this.’”

The University of Arizona’s IFC houses also received education in the form of personal stories regarding the risks of opioids. IFC houses participated in a program called Fraternities Fighting Fentanyl, where founder Clark Griffin opened up a dialogue with fraternity members about opioids and their inherent dangers.

Griffin, 75, started Fraternities Fighting Fentanyl in honor of his late son, Tyler Griffin, who tragically died in 2019 due to accidental fentanyl poisoning. Tyler had been prescribed medication to help manage pain for a wrist injury he had sustained at work, but when he ran out, he asked a neighbor in his apartment complex if they had anything that could help. The neighbor gave Tyler what they said was 800 mg ibuprofen, but was actually fentanyl.

Griffin approved of Pettit-Miller's initiative and was glad that the fraternity members in the UA community had multiple avenues for education in opioid prevention.

Embracing diversity on stage:How the Phoenix Symphony music director champions a broader sound

"It is a fantastic initiative, I think that him taking the ball and running with it to make that happen is more than commendable," Griffin said. "The essence of our two initiatives and how they are similar is that they are both based on the concept of education."

Former president of the University of Arizona IFC, Michael Walker, said he was glad the Greek life community had the opportunity to become more aware of the dangers presented by opioids, and is confident that this education will be beneficial for members moving forward.

“I think that it will really bring awareness to how bad it is and how it has impacted other people’s lives and their families,” Walker said. “And I think just having the access to something like the Narcan kits really opened up people’s eyes, and they see like, ‘Wow, this is a danger that is a common occurrence.’”

Pettit-Miller hopes his model of education and access can expand to other college campuses across the country. He has already been in contact with students from other schools like Arizona State University, the University of Michigan, the University of Miami and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to start similar programs.

On the UA campus, Pettit-Miller wanted to expand access to Narcan to be included in on-campus housing facilities, but the university's Housing and Residential Life department refused his proposal. However, Pettit-Miller said they were welcome to education and tabling events in the future.

Despite this setback, he is working with UA EMS to provide other opportunities for students to have access to Narcan. McGoldrick-Ruth mentioned that Pettit-Miller and UA EMS are working on starting outreach events and resource handouts at the EMS station, including both Narcan kits and fentanyl testing strips, to help provide access to the UA community at large.

Pettit-Miller was recently asked to serve as an advisor to the Pima County Board of Health’s Substance Misuse Advisory Committee, where he's excited to be able to continue helping the Tucson community.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: UA student Aidan Pettit-Miller aims to stop opioid deaths in Greek life