How a UC professor helped find the ancient city of Troy, searched for Trojan War evidence

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When you think of archaeology, the first name that likely pops up is Indiana Jones. As for real world professionals, back in the 1930s through 1960s, the best-known American archaeologist was Carl W. Blegen, a professor in the classics archaeology department at the University of Cincinnati.

“There was a time when Blegen was a household name in Cincinnati,” Jack L. Davis, professor of Greek archaeology at UC, once told UC Magazine.

If you spent time studying at the University of Cincinnati in the past 40 years, you might recognize the name from the Blegen Library, which houses, appropriately enough, the rare book archives and classics library.

But unless you were an archaeology student, you might not know of Blegen’s contributions.

Blegen became famous for helping uncover the ancient city of Troy, found in present-day Hisarlik, Turkey, and the setting for the Greek myth of the Trojan War as told in the epic poems of Homer.

Expedition to find the Troy of the Trojan War

Archaeology may not be all death traps and rolling boulders like in the movies, but Blegen’s expeditions did make international headlines.

After studying at Yale University and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens in Greece, Blegen joined the UC faculty in 1927. He was the first to be recognized by the Archaeological Institute of America with its Gold Medal for Distinguished Achievement.

Blegen gained renown for directing the excavation of Troy from 1932 to 1938, sponsored by the University of Cincinnati. William T. Semple, the head of UC’s classics department, proposed the expedition. His wife, Louise Taft Semple, the daughter of Charles P. Taft (half-brother to President William Howard Taft and publisher of the Cincinnati Times-Star), financially supported it.

Heinrich Schliemann, a German amateur archaeologist, started excavation of the ancient city in 1870. Schliemann had found that rather than one city, there had been at least nine built on top of each other, identified in layers. The Troy site was inhabited almost continually from 3000 B.C. to the Roman times in the first century A.D.

Part of Blegen’s goal was to find archaeological evidence of the Trojan War.

As you may remember from high school literature class, the Trojan War was a 10-year siege of Troy by the Greeks, triggered by the abduction of Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world and wife of King Menelaus of Sparta. The story features Greek gods, larger-than-life heroes and a wooden horse secretly packed with Greek soldiers, as told in Homer’s poems, “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey,” and Virgil’s “The Aeneid.”

Historians have generally regarded the Trojan War as a myth, but Blegen sought to find out if there were some truth to the stories. Did the Trojan War even happen?

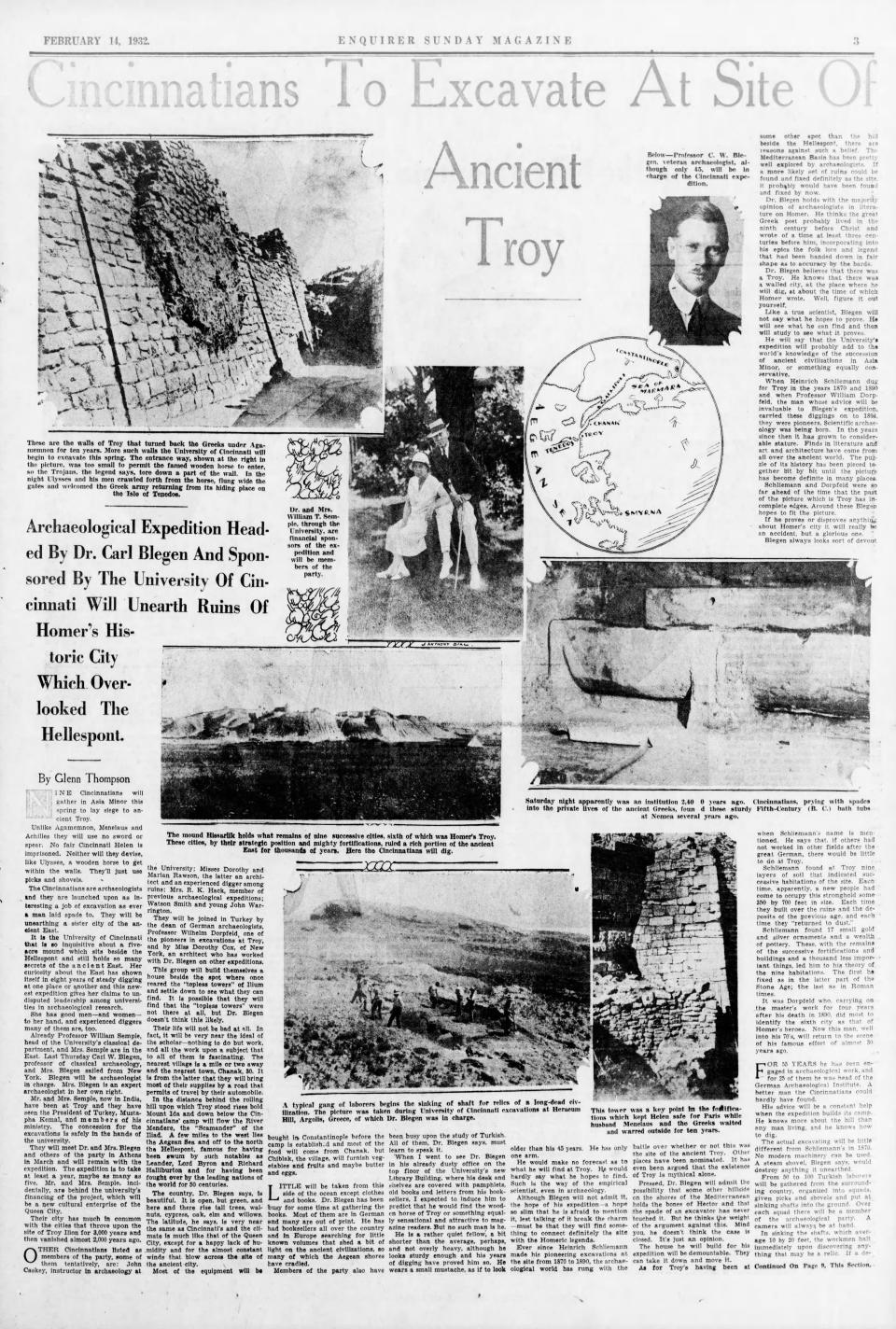

“Nine Cincinnatians will gather in Asia Minor this spring to lay siege to ancient Troy,” began a 1932 Enquirer Sunday Magazine feature by Glenn Thompson.

“Unlike Agamemnon, Menelaus and Achilles they will use no sword or spear. No fair Cincinnati Helen is imprisoned. Neither will they devise, like Ulysses, a wooden horse to get within the walls. They’ll just use picks and shovels.”

Blegen brought a more professional approach to the excavation. He found pottery remains that showed that the sixth version of Troy (Troy VI) went back several hundred years earlier than previously thought, to the Middle Bronze Age, and was ruined in an earthquake about 1300 B.C.

Examining the citadel mound that Schliemann had located, Blegen found evidence of burning, a full human skeleton outside the fortification wall and a number of bronze arrowheads, which he interpreted as evidence for the Trojan War in the seventh layer (Troy VIIa). That Troy was burned about 1200 B.C.

“If there is any truth in Homer’s epic of the 10 years’ siege of Troy by Greek forces under Agamemnon – and members of the Cincinnati expedition are convinced there is – this seventh Troy unquestionably was the one which fell through the ruse of the wooden horse and was put to torch by the victorious Grecian forces,” The Enquirer wrote when Blegen reported his findings in 1938.

Located the Palace of Nestor

The following year, 1939, Blegen led a joint expedition for UC and the Greek Archaeological Service, which unearthed the remains of a palace in Pylos, Greece. He was convinced it belonged to King Nestor of Pylos, who was mentioned by Homer.

They found a small bedroom with walls coated in stucco and decorated in frescoes, a lavatory and a terra-cotta bathtub. Also, a major find: clay tablets with Linear B script, a written language of Mycenaean Greece that predated the Greek alphabet.

Blegen told a journalist in 1962 of finding the tablets: “It was the time of the spring rains. The ground was very damp, and the tablets were soggy and horribly delicate. (Graduate student) W.A. McDonald, who was with us that year, and I spent day after day on our hands and knees, getting out the tablets one by one. When we dried them on wire screens, they became almost as hard as pottery, but still each tablet had to be cleaned, inch by inch, with toothpicks. We didn’t dare use acid then, as we do now. It was a chore, I can tell you – and we enjoyed every minute of it.”

The tablets were studied thoroughly and Linear B was finally deciphered in 1952.

Whether the palace belonged to the actual Nestor, or if in fact Nestor was a real person, is unknown, but Blegen never abandoned that theory.

“Now that a substantial palace of the right period is coming to light in fairly close proximity to the traditional Greek Pylos, I see no reason for hesitating to accept it as the very Palace of the Neleids, where Nestor and his sons entertained Telemachus,” Blegen told the Illustrated London News in 1939.

Work on the excavation stopped because World War II broke out. Blegen returned to the Palace of Nestor in 1952 and a more thorough excavation resumed.

He retired in 1957.

Blegen’s private life unearthed

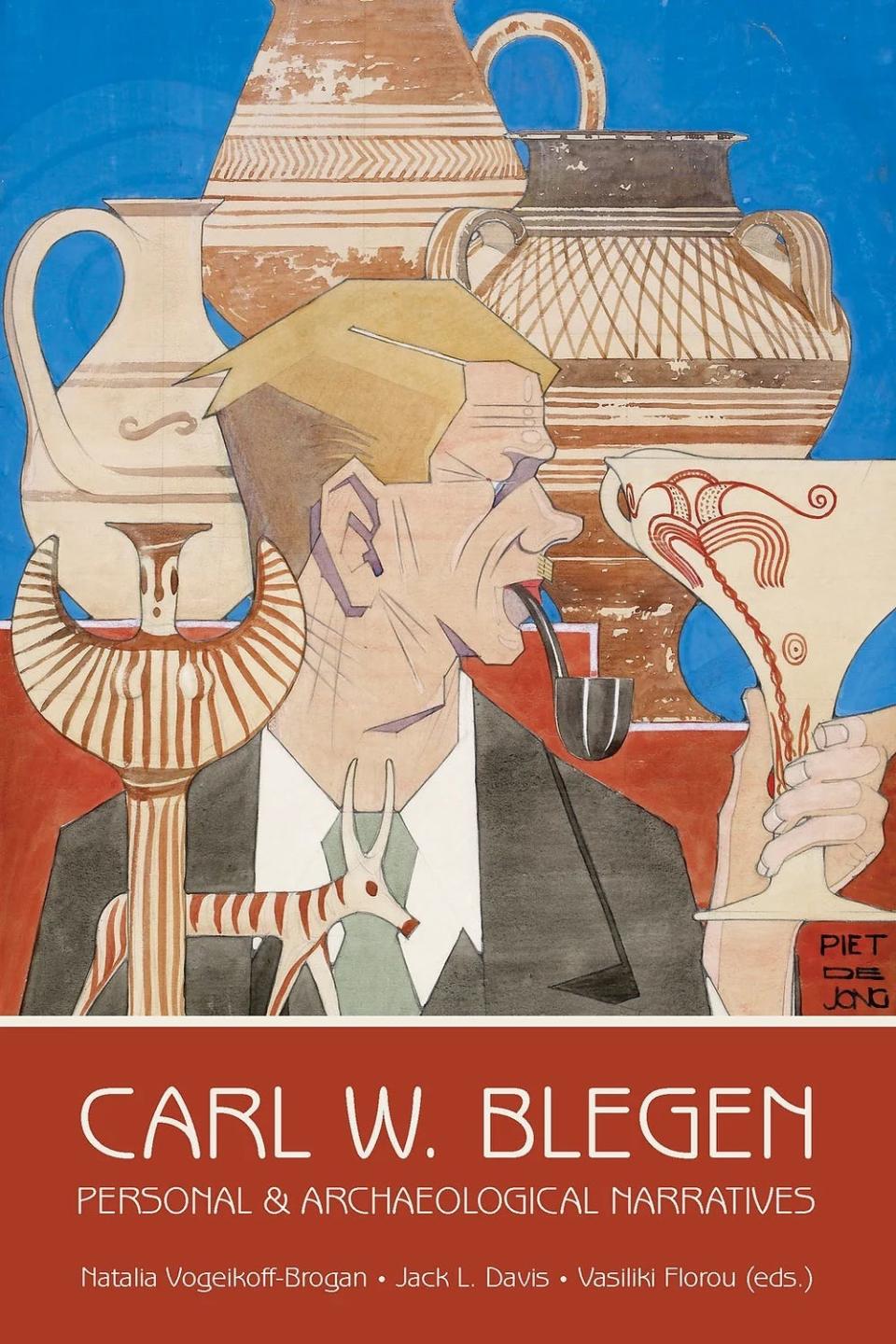

The biography “Carl W. Blegen: Personal & Archaeological Narratives,” edited by Davis, Natalia Vogeikoff-Brogan and Vasiliki Florou, shows there was more to him than just digging up historic ruins.

Something rarely mentioned was that Blegen was missing his right arm. It was amputated after a hunting accident when he was 15. In photos, he favored his left side, his prosthetic right arm set awkwardly, always wearing a glove.

The biography spends a chapter on the unconventional relationship of Blegen and his wife, Elizabeth Pierce Blegen, and another couple, Bert Hodge Hill and Ida Thallon Hill. All four were accomplished archaeologists.

When Blegen proposed marriage in 1923, Elizabeth didn’t want to end her longtime relationship with her lover, Ida. So, it was arranged for Blegen’s friend Bert, the director of the American School, to marry Ida. The two couples lived together in a house in Athens in what they called “the Family” or the “Pro Par,” their nickname for “Professional Partnership.”

Few people knew about their arrangement at the time, but there were whispers.

After retirement, Blegen collaborated with fellow UC archaeologist Marion Rawson on an 11-volume text on UC’s expedition to Troy, and a four-volume work on the excavation of King Nestor’s Palace. He died in 1971, at age 84.

UC’s former main library, built in 1930, was renovated in 1983 and renamed the Carl Blegen Library.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: How the University of Cincinnati helped find the ancient city of Troy