UCLA wins $3.65-million grant to build 'Age of Mass Incarceration' archive with LAPD records

With a $3.65-million grant and a trove of Los Angeles Police Department records dating back decades, scholars at UCLA have launched a new archival project aimed at independently preserving and dissecting the history of mass incarceration in L.A.

The project, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and called "Archiving the Age of Mass Incarceration," will seek to reveal in new ways how the Los Angeles region became a global outlier for imprisonment — with the largest jail system in the most heavily incarcerated nation in the world — and what the implications of that legacy are in the city's most heavily affected communities, organizers said.

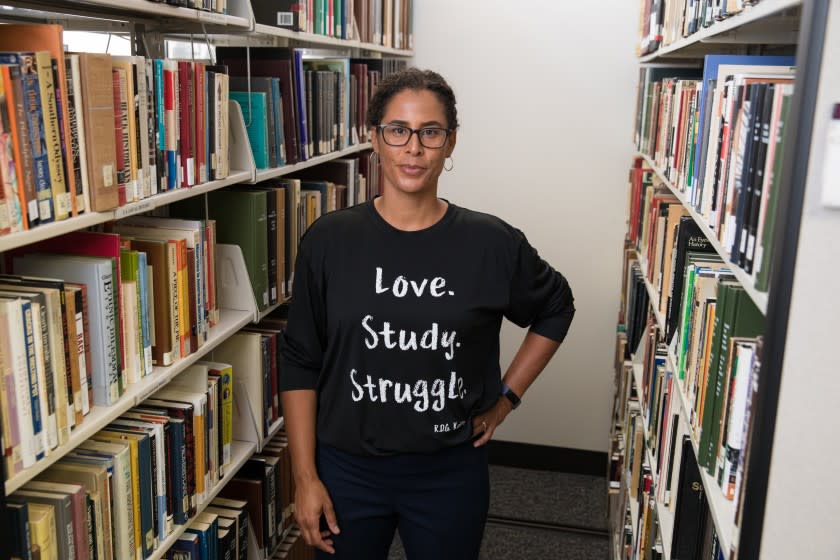

In addition to 177 boxes of LAPD records from the 1970s through the early 2000s, which the university fought for and won access to in court, the project will seek out and include oral histories and other ephemera from community members whose lives are captured in the documents or who were otherwise affected by the region's aggressive criminal justice pipelines, said professor Kelly Lytle Hernández, who heads UCLA's Million Dollar Hoods team and leads the latest project.

"This is an example of community control over policing. We are taking control over the archive of what happened, and we will be curating what gets released and how, and we will be describing it, filling it with meaning," Lytle Hernández said. "It's reparative work."

Lytle Hernández, a MacArthur "genius" fellow who directs the university's Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies, will partner with scholars from the school's three other ethnic studies centers: the Asian American Studies Center, the American Indian Studies Center and the Chicano Studies Research Center.

Elizabeth Alexander, the Mellon Foundation president, said she has been impressed with Lytle Hernández's work with Million Dollar Hoods — which maps the high cost of incarceration in L.A.'s diverse neighborhoods — and is excited to help her in the work of ensuring the city's history of mass incarceration is "properly interpreted, preserved and taught."

"We are incredibly excited to see, in the years ahead, what comes from this research team," Alexander said.

The goal of the three-year grant is ultimately to have the archive accessible to the public on a new digital platform.

Professor Karen Umemoto, director of the Asian American Studies Center, said that platform — which will be built through a collaboration between the four ethnic studies centers — "will catapult our centers into the digital future in knowledge sharing and knowledge production."

The full scope of the project is yet to be determined, and that's by design.

At its core are the dozens of boxes of LAPD records, from "kind of boring daily stuff to the sensational," said Marques Vestal, a post-doctoral scholar and incoming assistant professor of critical black urbanism at UCLA who has worked with the archive.

Vestal said there are overtime sheets and operational directives, corporate donation checks and daily correspondence between commanders, reports on tactical operations and investigations, documents about incidents at international consulates and never-before-seen reports on police shootings.

The records cover four decades of policing, including many from the 1980s, when law enforcement was "ratcheting up the drug war," Vestal said.

Lytle Hernández said the "counterpoint" in the archive to all the police records will be "the voices and materials, life materials, ephemera of the people who have been most impacted," from the Black community to indigenous L.A.-area communities that have been forgotten in past scholarship on the region.

She said she expects records that show the true cost of incarceration on communities — bail bills, commissary costs — to be included in the collection, as well as personal letters between those behind bars and their loved ones on the outside. However, community members will ultimately shape what ends up in the collection, she said.

"Really we are going to be looking to our community partners to say, 'Look, this is how I experienced this, and this is what I want to be part of the story,'" Lytle Hernández said. "There will be plenty of stuff that people won't want to be saved [because] it's too hard, it's too traumatic."

Both Lytle Hernández and Alexander said the project comes at a critical inflection point culturally, and was inspired in part by recent mass demonstrations against police brutality and for racial justice — including in L.A. this past summer — that have awoken more people than ever to the injustices and inequities that have been pervasive in the nation's criminal justice system for years.

"We have a moment in the country where many, many more people are understanding the racial inequities that are a shaping factor in American life," Alexander said.

Lytle Hernández said she is approaching the project "with the hope and understanding that we're hitting a turning point in American history and moving away from mass incarceration," such that documenting the history before records are destroyed and the narrative is distorted is critical.

She said she also hopes the archive will continue to grow from new acquisitions, including more internal records from the LAPD.

"It's quite clear to me," she said, "that there are still tens of thousands of more records to be acquired."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.