UF professors: Resurrecting Fort Mose, America’s first sanctioned free Black settlement

More than 300 years ago, a crowded dugout canoe carrying 11 exhausted African freedom seekers arrived in St. Augustine. They had journeyed more than 200 miles from South Carolina, where they had been enslaved by English settlers.

When they arrived that day in 1687, Spanish officials in St. Augustine gave them sanctuary and refused to return them when English slaveowners demanded their fugitive slaves back. They were the first of many Africans to reach Spanish Florida. Six years later, King Charles II of Spain decreed that all who fled Protestant colonies seeking baptism into the “true faith” of Catholicism would be freed.

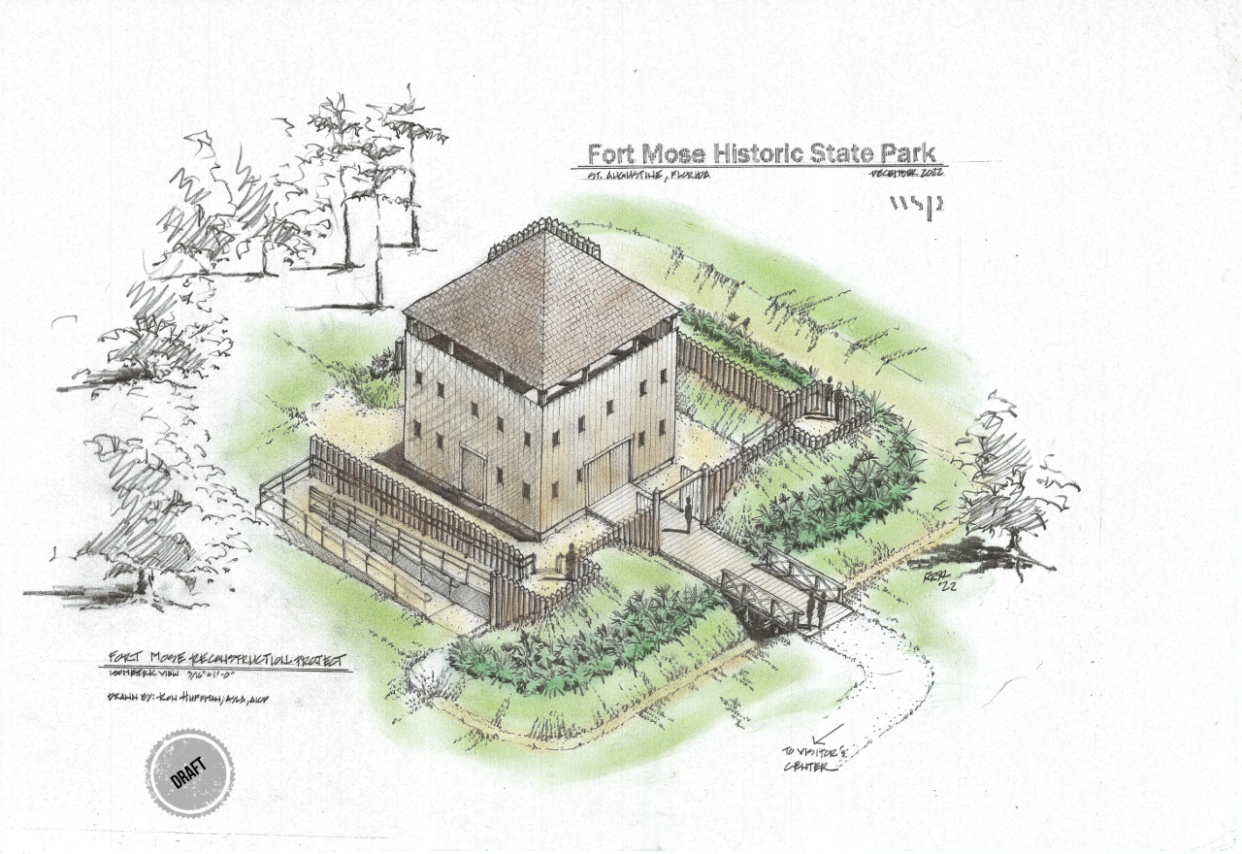

Today, three centuries later, a tribute to those freedom seekers is rising on the edge of a Florida marsh — a physical representation of Fort Mose, the settlement and fort built just north of St. Augustine by these formerly enslaved people. Although no trace of that fort remains today — other than a faint outline captured by satellite scanners — its appearance is being resurrected through historical documents, maps, archaeological data and space age imagery.

The fort reconstruction is being conducted by the Florida Park Service, thanks largely to the dedication and grass roots determination of the Fort Mose Historical Society and Florida State Parks Foundation. The society has united residents of St. Augustine under a common cause: protecting, promoting and interpreting this remarkable site and its story.

Today, Fort Mose is not only a part of Florida’s award-winning state parks network but is also a National Historic Landmark and a UNESCO Site of Memory for the Routes of Enslaved Peoples.

After the Spanish decree of religious sanctuary, many other freedom seekers seized the opportunity and made the dangerous journey to Florida. This first underground railroad ran South. By 1738, more than 100 people had made their way to St. Augustine.

In that year the town and fort of Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose (pronounced “MOSAY”) was established about 2 miles north of the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine.

The fort was badly damaged during the Battle of Bloody Mose in 1740 and subsequently abandoned. In 1752 a second, larger fort was built close to the location of the destroyed original, and the Mose settlers returned. They remained until Florida became a British colony in 1763, and the 34 families at Mose joined the Spanish evacuation to Cuba.

Their story, nearly lost to time, resurfaced in 1985, when a University of Florida archaeological team — aided by new NASA imagery — located the second Fort Mose and submerged remnants of the nearby first fort.

Excavations revealed details of the second fort, and the lives of the people who lived at Mose were reflected in shards of pottery, lead shot and gunflints, along with many other artifacts. These provide a foundation for interpreting Fort Mose to the present-day public.

Letters: Jacksonville Jaguars need to show fans some love, keep 'home' games at home

Fort Mose changed the international political landscape of 18th-century America and has received prestigious historical site designations. It embodies the fight for freedom in the early days of our country and highlights a facet of African American history that is dramatically different than the familiar story of slavery and oppression.

Despite its historic importance, the fort and its message are still relatively unknown. Creating a physical representation of the long-lost original fort will bring this dramatic history to life.

The current reconstruction of Fort Mose is a symbol of how local communities, politicians, scholars and state agencies can work together for a common good. It is one that should be repeated more often.

Kathleen Deagan, distinguished research curator emerita and Lockwood professor of archaeology emerita at the University of Florida, led the excavation at Fort Mose. She is co-author of “Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom.”

Jane Landers is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt professor of history at Vanderbilt University and historian of Fort Mose. She is the author of “Black Society in Spanish Florida.”

This guest column is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Times-Union. We welcome a diversity of opinions.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Fort Mose reconstruction will bring important Black history to life