Ukraine Seems to Be Slipping off the Agenda at the U.N. General Assembly

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

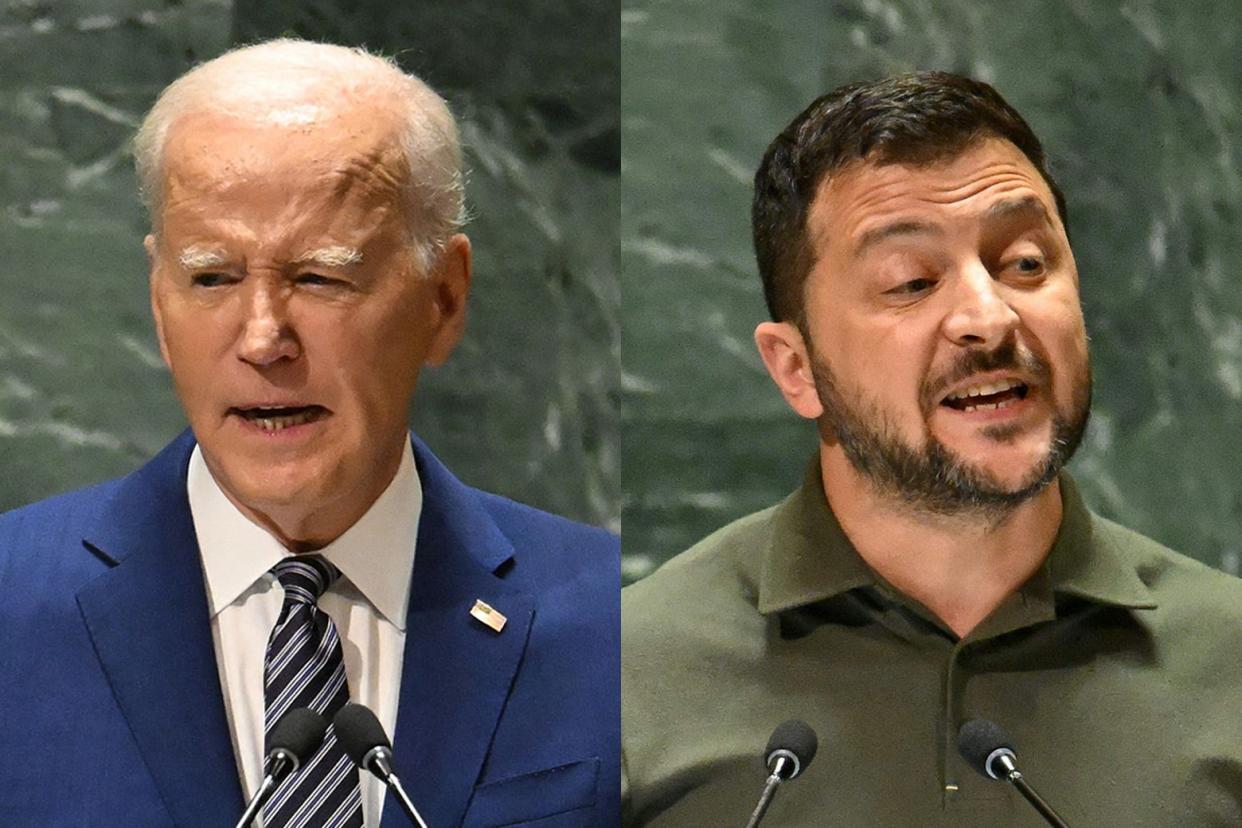

There are five permanent member states on the United Nations Security Council—but of all their leaders, Joe Biden was the only one to show up at the U.N. General Assembly this week. That may be the most significant thing about Biden’s speech Tuesday morning.

Russia’s Vladimir Putin, China’s Xi Jinping, France’s Emmanuel Macron, and Britain’s Rishi Sunak all had other, presumably better things to do. Another prominent world leader, India’s Narendra Modi, stayed home as well, possibly exhausted from having hosted the G20 summit just last week.

This unusually large spread of high-level no-shows could mean that the General Assembly—which used to be a major event, the one occasion when all the world’s leaders gathered in one place and some of them took a moment to meet quietly on the sidelines—is simply no longer as big a deal as it once was.

Perhaps, for now anyway, it’s just as well. Washington’s tensions with Moscow and Beijing are so fraught that it may be best for their leaders to avoid meeting face-to-face. A few days before the U.N. get-together, Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, met in Malta with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, for what the White House readout called “candid, substantive, and constructive discussions.” Best for senior officials such as these to “tee up” the issues—scoping out where accommodations might and might not be made—before their bosses risk the stakes of a great-power summit. (After the Malta meeting, Wang flew to Moscow for a meeting with his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov—suggesting that Xi is now playing the same sort of triangular politics with the U.S. and Russia that American presidents once played with Russia and China.)

Meanwhile, Biden tried to use the absence of his peers to his advantage. He devoted most of his speech to a call for expanding international institutions to include low- and medium-income nations that have been ignored over the past decades, and thus create a “more equitable world for all people because we know our future is bound to yours.”

Leaders of the Global South—Africa, Latin and South America, and parts of Asia—have recently been pushing for a greater say in global affairs. Much of the General Assembly’s agenda this year is devoted to issues that resonate with this discontent—“sustainable development,” “financing for development,” and “universal health coverage.”

Putin and Xi, in their own ways, have adopted this rhetoric and tied it to “anti-imperialist” themes as a way to displace U.S. influence in what used to be called the Third World. Putin has done so to keep these nations at least neutral toward his war with Ukraine; Xi has touted China’s Belt and Road Initiative as an alternative to Western finances. Both have been fairly successful in these campaigns—which is ironic and infuriating, given that BRI has its own sets of inequities (as some of its clients have discovered) and that Putin is conducting the most aggressively imperialist war in decades.

Biden’s speech—his very presence at the assembly, contrasted with Putin’s and Xi’s absence—marked an assertion that Western democracy stands as a better vehicle for these aspirations. He cited the tens of billions of dollars that the U.S. has invested in development, world health, and combating climate change in just the two years of his administration, as well as his own role in coordinating tens of billions more from other nations. He urged the assembly’s leaders not to follow Russia’s path, warning that if Putin succeeds in Ukraine, he could commit aggression against them.

In a coupling of both messages (“I’m Here, They’re Not” and “Don’t Cuddle Up With Moscow”), Biden was scheduled to meet with the presidents of five Central Asian nations—Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. A senior U.S. official noted that this “C5+1 summit” will be the first-ever such meeting with those nations and that they will discuss “regional security, trade and connectivity, climate, and reforms to improve governance and the rule of law.” The official did not note that all of these nations used to be republics of the Soviet Union and that Putin is keen to bring them back into Moscow’s orbit.

Biden’s message may have reassured the leaders of long-neglected nations to some extent—but there was a specter looming in the shadows: that of the 2024 U.S. presidential election. Biden has a long record of supporting alliances; his words on inclusivity and equity are consistent with that record. (And by the way, his delivery of those words was fine. Yes, he looked old, but not doddering, except for a couple of slurred lines, which seemed products more of his lifelong stutter than of any geriatric infirmity.)

The unspoken concern, however, was how long Biden will be around to deliver action—whether someone else will be president a mere year and a few months from now, and whether that president might be Donald Trump, who detests international organizations, cares nothing about global inequities, and will likely pull whatever funding Biden devotes to leveling measures.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who was attending the General Assembly for the first time since the war began, is especially concerned about this possibility. Upon his arrival in New York on Monday, he visited wounded Ukrainian soldiers at a hospital in Staten Island. He watched Biden’s speech at the U.N. Tuesday morning (Biden’s commitment to Ukraine’s cause was the only line that prompted applause) and gave a speech of his own that afternoon. Far from the burbling homily of thanks and beseeching for more that some expected, Zelensky’s speech was a fiery call for unity and justice in the face of Russian terror and war crimes—not just to restore Ukraine but to prevent aggression against others and to create a space where the world’s other urgent crises, such as climate change, can be solved.

On Wednesday, Zelensky is slated to go to Washington, where he will meet with Biden in the White House and with several lawmakers on Capitol Hill—whose support he needs, regardless of what happens in next year’s election, especially since it now seems the war will last longer than he and his supporters had hoped.

The war in Ukraine, which was the dominant (almost the sole) topic of last year’s General Assembly, seemed to be slipping off the agenda this year—Biden’s speech devoted only a few lines to the war, at least directly. Zelensky sought to restore its prominence. Even without his speech, the war loomed as a constant backdrop of the session—a rallying cry for sovereignty and territorial integrity (“core tenets of the U.N. charter,” as Biden put it) and a test of whether the U.N., either as an institution or as a collective of nation-states, is up to doing much about it.

At the moment, it seems not to be. Much of the Global South wants no part in the new East-West divide. Many of the leaders who could help put an end to the war, including the one who started it and could stop it single-handedly, did not bother to show up—and seem not to see the U.N. as the place where such crises can be solved.