Ukraine war triggered memories for Okemos man. So he went overseas to help

The war in Ukraine is personal for Ody Norkin of Okemos.

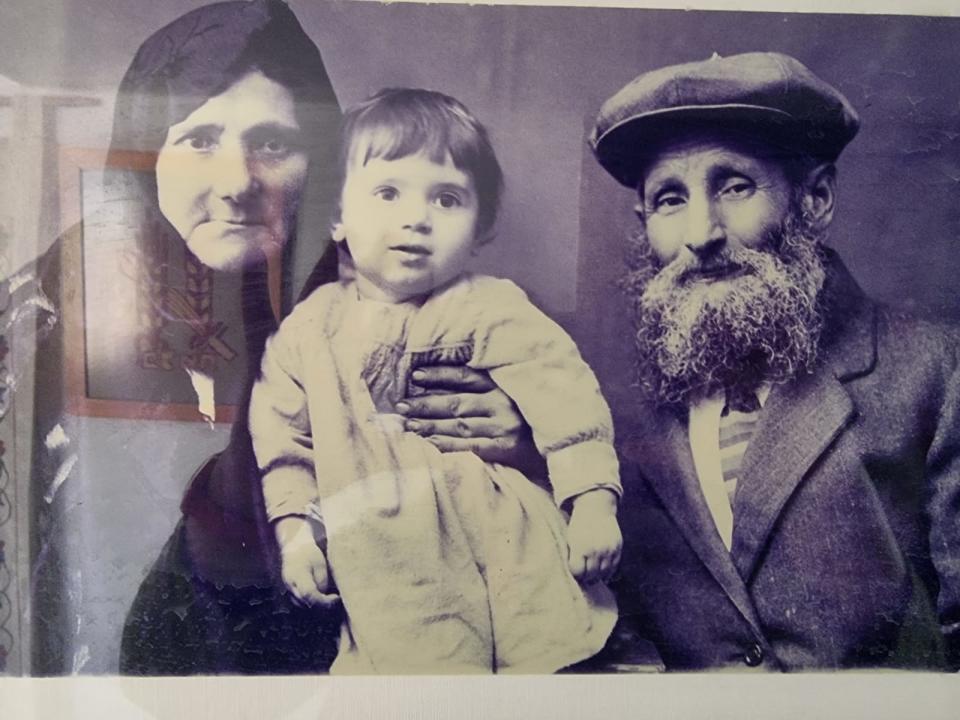

As he watched the news showing platoons of Russian soldiers storming into Ukraine, he thought of his grandparents. They were killed in the streets of Odessa during the Holocaust in 1941. He treasures a photo of them holding his father as a baby.

Norkin, 67, was born in Israel and served in the Israeli Army during the 1973 war. He came to the United States in 1978 and now serves as vice president of Michigan Flyer, which transports passengers from Lansing and Ann Arbor to Detroit Metro airport.

As he monitored the war in Ukraine, Norkin said he became frustrated by Israel’s neutral stance. The exodus of people from Ukraine to neighboring nations moved him, and he knew he needed to do something.

In early March, Norkin called Hendel Weingarten, the rabbi at a Jewish Chabad House in East Lansing. Did the rabbi know anyone in Ukraine who could connect Norkin with people who needed help?

Weingarten suggested his friend and fellow rabbi, Avraham Wolff in Odessa.

The restless Norkin soon texted Wolff: “I am tired of sitting on my hands. I know all about buses and transportation. Is there anything I can do to help the folks in Odessa?”

Wolff replied, “Actually, we don’t need transportation help but it would be extremely helpful if you showed up with an ambulance. You could drive passengers who can’t handle buses, who must lie down. We have many infirm people here who need to be taken to a safe place.”

That text exchange happened on March 13. Norkin vowed to deliver an ambulance to Odessa.

Making plans for travel to Ukraine

Norkin’s family and friends weren’t quite as enthusiastic about his potential trip to Ukraine. They told him he was crazy to go because he couldn’t speak the language and didn’t know anyone there. They reminded him there was a war going on and there already were experts on the ground who knew how to help refugees.

They pleaded with him not to go. Everyone except his wife, Rachel. She knew he wouldn’t listen.

With his decision made and plane tickets purchased, Norkin withdrew $10,000 in cash from a personal bank account. He bought a belt runners use for hydration and instead used the pouches to store the cash.

After deciding to fly into Romania, Norkin went back to Weingarten to see if the rabbi had a contact in Bucharest who could help him secure an ambulance.

Weingarten suggested Rabbi Naftali Deutsch at the Chabad house in Bucharest. So, on March 14, Norkin left on his mission. He traveled alone, without a sponsoring organization or much of a plan.

When asked whether he was apprehensive to travel to a dangerous part of the world, Norkin said, “No, my only concern was that I was three weeks too late. People are dying over there.”

He landed in Bucharest on a Wednesday night, rented a nine-passenger van and stayed at a third-rate hotel near Deutsch’s synagogue. When he entered the building the next morning, he noticed boxes of clothes and food for Ukrainian refugees.

Deutsch was sympathetic to Norkin’s mission, but he couldn’t help him procure an ambulance. But he did have a suggestion: “Why don’t you call Marco Katz? He can probably help.”

Deutsch was right.

Katz knows everyone and everyone knows him. He was born in Romania, immigrated to Israel, moved to the U.S. for a time; he then moved back to Israel and now works in Romania. Officially he is head of the Romanian Zionist Association, but he is also a podcaster, translator and all-round fixer.

And a perfect match for Norkin’s boundless energy.

“Ody gave up his life for five weeks to do something that I thought was impossible," Katz said. “He was so determined to get it done that I just followed him. Ody doesn’t take no for an answer. What Ody did would take an institution to accomplish.”

'Whatever I can do, I'll do'

While Katz focused on the ambulance project, he suggested another job for Norkin. “I’m here to work,” Norkin said. “Whatever I can do, I’ll do.”

Katz conscripted Norkin on a trip to Chernivtsi, Ukraine, a 10-hour drive, to provide generators, sleeping bags, fire extinguishers, cooking gas and other materials for a town they believed had no utilities. With money from the UK Jewish community, they purchased the supplies from a Home Depot look-alike.

“Why are we buying only five generators?” Norkin asked. The answer: That was how many the group could afford.

When Norkin realized how cheap the generators were compared to U.S. prices, he bought two more with his own money.

“We were supposed to meet the guys from Chernivtsi on the Ukraine side of the border, unload the stuff, do a U-turn and come right back to Romania,” Norkin said. “But the Ukrainians had a tiny car that wouldn’t hold the load, so we drove an extra 40 minutes into Ukraine to unload. I was nervous because of the curfew and it was getting close to dark. I made a promise to my family.”

Norkin arrived back at the Romanian border 30 minutes before the 10 p.m. curfew and stayed overnight at a small Romanian town near Siret.

“It was filled with media, reporters, evangelicals,” Norkin said. “It was a tent city, quite a scene.”

Norkin then received another assignment from Katz. Could Norkin pick up nine refugees from Moldova and Kharkiv, who were stranded in the port city of Mangalia, and transport them to Bucharest?

When he arrived at the designated pick-up point, the forlorn families, with their bags and luggage, were waiting for him.

“I could hardly get all of their stuff in the van,” he said. “Nine women and children with all of their stuff. It was packed solid.”

On the drive to Bucharest, he learned about the tragedies of war from a widowed grandmother who had raised her three grandchildren, and had to leave her 19-year-old grandson behind to fight.

“Leaving was the most agonizing decision of her life,” Norkin said of the woman who was tearful the entire journey.

The following morning, Norkin helped at the airport. There were five buses filled with people taking chartered flights to Israel. Many did not have passports so they worked through embassies to get the necessary documents.

Norkin found himself pushing seniors in wheelchairs and leading Hebrew singalongs. He also talked to the Israeli volunteers about how to license an ambulance to send to Odessa. They were no help.

That’s when Norkin turned back to people in the U.S.

He contacted Okemos lawyer David Mittleman to see if Mittleman could ask Rep. Elissa Slotkin, D-Holly, to help push through the bureaucracy.

“I remember calling Elissa when she was on the floor of the House (of Representatives) — and she took the call and immediately went to work on it,” Mittleman said.

“Ody reached out to me and my office for help after his efforts had been caught up in some diplomatic red tape,” Slotkin said. “We were eager to pitch in, and contacted the Romanian ambassador. The ambassador and his team made this a top priority and we were thrilled that it worked out.”

A Romanian envoy then called and asked Norkin what kind of help he needed.

“I need a title and I don’t have three weeks to wait for it,” Norkin said. “In the States, it would take two hours.”

The envoy connected Norkin with a man named Cornell Vulpe.

Vulpe found a way around the red tape, creating a nonprofit in Ukraine that would take ownership of the vehicle with temporary plates to get them into Ukraine with Katz and Norkin as their agents. The task was done in three days, instead of three weeks.

Michigan support for the Ukrainian cause

In the meantime, Katz had located a used ambulance to buy. It seems Hollywood movies made in Romania are required to have an ambulance on site for possible emergencies, and he was able to find a Mercedes Benz ambulance for $6,400.

When Norkin first embarked on his mission, he intended to pay for the ambulance with family and personal money.

Weingarten, the Lansing rabbi, had other ideas.

He called Amy Shapiro, executive director of the Greater Lansing Jewish Federation, and told her of Norkin’s mission.

Then Shapiro, along with Stan Kaplowitz, treasurer of the federation, quickly raised money to pay for the ambulance.

“This is tangible,” Kaplowitz said. “People know exactly where the money is going. And they know and respect Ody Norkin.”

Shapiro added, “Ody embarked on an incredibly brave mission and in line with our Jewish values. It takes a lot of guts.”

After taking possession of the ambulance, Norkin stocked it with defibrillators, monitors and other medical equipment he paid for with his own money.

His goal was now in reach: He was ready to deliver the ambulance to Odessa.

Norkin and Katz drove about 11 hours to the ferry that took them over the Danube River and to the Ukraine border. They waited for four hours at the border crossing.

Nelli Kuznietsova, a knowledgeable volunteer from the Chabad house, stayed on the phone with the team during the entire night of travel through Ukraine. Kuznietsova understood the 21 military roadblocks and how to get through them — no pictures, no video, keep your hands where they could see them, etc.

During the all-night drive, Katz leaned over to Norkin and said, “What if suddenly a Russian tank would come out of the woods, what should I do?”

They both laughed, knowing they had no idea what they would do.

Norkin got sick and ran a fever during their 21-hour trip to Odessa. Yet he had the joy of handing over the documentation and keys to Rabbi Wolff.

That joy was short-lived. He slept for two hours before the head of EMTs took him back over the border to Romania. The return trip was much faster with a driver who knows the tricks to avoid roadblocks and traffic jams.

After the grueling 36 hours of travel, Norkin had accomplished his mission. He was ready to come home to Michigan after four weeks abroad.

But his return trip would be delayed. The illness he experienced on the trip to Ukraine wasn’t a cold. It was COVID-19. A positive test at the airport led to 10 days of quarantine.

With nothing to do but wait, Norkin, by way of Katz, was enlisted to secure a second ambulance, this one for Dnipro, Ukraine’s fourth largest city. Using his earlier experiences and connections, this assignment was much easier.

Norkin was able to identify another emergency vehicle and in early May he will fly back to Romania to deliver it. The Greater Lansing Jewish Federation funded the effort with local donations.

“His efforts over the last few months in Europe have saved lives and his commitment to this mission has been nothing short of inspiring,” Slotkin said. “During times of crisis like this, we get a glimpse of the best of humanity — and Ody Norkin has set an example for us all with his bravery and selflessness.”

Ken Glickman is a freelancer for the Lansing State Journal.

This article originally appeared on Lansing State Journal: Ukraine war: Ody Norkin, Lansing Jewish community deliver ambulance