A Ukrainian family finds a warm welcome in NJ, but longs to return home

Olena Oborevych awoke before dawn to the sound of explosions ringing out over Kyiv, Ukraine, one year ago. Turning on the news, her fears were confirmed.

Russia was launching an all-out invasion of her country, sending in columns of troops and tanks and firing missiles and long-range artillery toward Ukrainian airfields and cities. One of the first targets was Kyiv, the capital city of 3 million where she lived with her elderly father.

As the Battle of Kyiv raged over weeks, Oborevych felt her walls shake and watched her windows warp as warplanes roared and missiles fired in the distance.

“I was in shock,” Oborevych said in an interview. “I didn’t know what to do. I heard people talk about the possibility of this, but nothing could prepare you for witnessing something like this.”

Many miles away in Hackensack, Oborevych’s daughter Mariya Gonor was monitoring news reports and growing more worried for the family she left behind in 2004. She scrambled to find drivers willing to take her relatives — her mother, grandfather, aunt and cousin — over a treacherous route to neighboring Poland.

Gonor desperately wanted to bring them to the United States, but pathways for refugees were limited and could take years. That changed on April 25, when the Biden administration launched Uniting for Ukraine, a fast-tracked program allowing Americans to sponsor Ukrainians displaced by war.

Through the program, private citizens volunteer to provide financial and social assistance to displaced Ukrainians. Sometimes called U4U, the program grants “humanitarian parole” status to Ukrainians allowing them to stay in the U.S. for two years.

Last summer, Gonor’s mother, grandfather, aunt and cousin arrived in New Jersey. They were among 267,000 Ukrainians who have been admitted into the U.S. since March through the sponsorship program and other pathways, federal data shows.

“It’s a game changer,” Gonor said. “We don’t know when this war is going to end. I wanted my family with me.”

Americans open their homes

Russian President Vladimir Putin launched the Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine on several fronts, setting off fierce fighting that spurred the biggest refugee crisis in Europe since World War II. In all, about 8 million Ukrainians fled to neighboring countries including Poland, Hungary, Moldova and other countries across Europe, according to the U.N. Refugee Agency.

In March, as fighting grew closer to home, Oborevych decided to leave with her father.

“I was terrified there would be the same kind of iron curtain like when we were under the USSR,” she said, recalling a time before Ukraine gained its independence from Russia in 1991. “We couldn’t travel freely. I wouldn’t be able to see my children.”

Gonor scrambled to find drivers to take them over the border, not an easy feat in a country facing a mass exodus. For weeks, she’d wake up at 6 a.m. to check if they got out. Finally, all four relatives headed over the border to Poland. The drive, normally five hours, took 24 hours along an indirect, traffic-choked route to avoid fighting and bombed-out roads. Once in Poland, they stayed in an Airbnb amid a housing shortage, and Gonor sought ways to bring them to the United States.

When Uniting For Ukraine went live online, Gonor was ready at her computer, downloading and filling out necessary forms. She passed security and financial background checks, and her application was approved about three weeks later. Her aunt and cousin arrived in June. Her mother and grandfather came in August.

The Biden administration committed to taking in at least 100,000 people through the new sponsorship program, but the program soared beyond those numbers as Americans stepped up to offer their assistance.

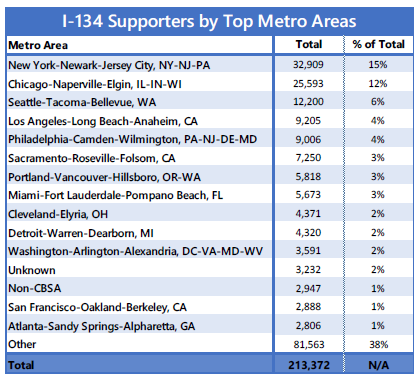

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which oversees the program, has gotten 213,000 requests to support Ukrainian citizens. The largest number of supporters came from the New York-Newark-Jersey City metro area, totaling nearly 33,000 applications, USCIS reported.

Ukrainians with humanitarian parole can get work in the U.S. and, under a bill Congress passed in May, can apply for federal programs to obtain cash benefits, health insurance and food assistance.

Building off that success, U.S. officials have extended sponsorships and temporary humanitarian parole to Venezuelans, Haitians, Cubans and Nicaraguans. Then, in January, officials launched the Welcome Corps, a program that enables Americans to sponsor refugees from around the world for permanent resettlment.

Refugee advocates have expressed support, but they also have urged the U.S. to do more to invest in traditional resettlement, which faced severe cuts during the Trump administration. Just 25,465 refugees were admitted during fiscal year 2022, far below the cap of 125,000 set by the administration last May. About 1,610 Ukrainians were among the resettled refugees.

For now, the family’s situation is temporary. U.S. officials have not stated what will happen to humanitarian parolees from Ukraine when they reach the end of their two-year period.

“We are definitely worried about the possibility the war will continue to go on and this program will end,” Gonor said. “But I don’t think the nation will allow that to happen.”

'Ukraine is my country'

In the past year, Ukrainians have launched powerful counterattacks, holding ground against the Russians, who withdrew from Kyiv in April. With robust military aid from West — including $24 billion in security assistance from the U.S. — Gonor and her family believe Ukraine will prevail.

Until that happens, they are adjusting to life in New Jersey. Oborevych, a former social services manager, is learning English online through Church World Service, a refugee resettlement organization. Her father, Volodymyr, who is 85, is receiving health care he needs to treat ailments and high blood pressure. Gonor's aunt, Yuliia Danylevska, is continuing to run an online store selling handbags that she had before the war.

Gonor’s cousin, Anastasiia Leshchenko, 16, is enrolled in an English as a Second Language program at Hackensack High School, where counselors and staff have surrounded her with support. She’s become a big fan of the New Jersey Devils after watching a live hockey game.

Still, the family members said they feel sadness and guilt for leaving the country and its people in a time of crisis. "People are dying, “ Danylevska said. "Children are dying. They are destroying cities. The country is really standing by while someone is trying to tear it apart.”

Oborevych said she was deeply grateful to Poland and the United States for taking them in and providing services they need to survive. And she is grateful to her daughter in Hackensack who worked tirelessly to get them out of their city under bombardment.

Now, she hopes and waits for Ukraine to be free.

“I really want to be able to go back home," she said. "No matter what, Ukraine is my country and that is my home."

The story has been updated to reflect that 267,000 Ukrainians entered the United States since March through the Uniting for Ukraine program as well as other pathways.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Ukraine War: NJ families reflect one year later