"Ukrainians should not be expected to help Russians deal with their feeling of guilt," Sofiia Andrukhovych

Amadoka, the latest novel by Sofiia Andrukhovych, is about to be translated and published in 15 countries, including the UK, the United States, and France. This magnificent novel tells about the distortion of memory during the genocides that took place in Ukraine over the past hundred years: the Executed Renaissance, the Holocaust, and Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine. Lake Amadoka, which was marked on old maps of Ukraine and later disappeared, became a metaphor for the oblivion in which we sink to hide from pain and our own mistakes. The eponymous novel could now help put Ukraine back on the mental maps of Europe.

Today, October 4, a collection of essays Andrukhovych wrote for foreign media during the full-scale invasion is coming out in France. These days, Sofiia has many speaking engagements in Europe, although she regularly declines invitations to participate in the same events with Russians. She lives and works in Kyiv.

Our conversation takes place against the flare-up of arguments over the question of whether Ukrainian intellectuals should participate in public discussions with Russians and collaborate with them on creative projects. We also talk about how the war is changing the social role of the writer and drawing Europe’s attention to Ukrainian literature—and about how literature can overcome Europeans' war fatigue and prevent the war from becoming normalized in their perception.

"Writing is an ongoing effort to capture the essence of humanity."

How did Amadoka generate so much interest in Europe? Where was the translation of the novel first published?

The first translation came out in Croatia. They made a high-quality translation very quickly. And the book was well-received. Many local reporters contacted me, especially in the first days of the all-out war. They’d already read my novel, and we could talk about it and about Ukraine and the war. I had the impression that the Croats could feel us on a very subtle level, emphasize with us, and understand us.

But the biggest wave of attention came after the novel was published in Germany and Austria. They divided it into three parts because it is a big book. So far, only the first part has been published—the one about the war in the Donbas and the soldier who lost his memory. The translators are just finishing the second part, which deals with the Holocaust and the relations between the Jews and the Ukrainians on the eve of World War II.

Sofiia Andrukhovych at the presentation of the novel "Amadoka" at the Book Fair in Istria, Croatia

And when is the translation scheduled to be released in the UK and the United States?

Oh, not so soon—not until 2026, if I’m not mistaken! But in these countries, Amadoka will be published in its original form, as a single book.

Why do you think your novel has attracted so much attention from European publishers?

I think that Amadoka can help people today understand many things about Ukraine. Or to awaken interest in important Ukrainian issues, or simply to motivate people to explore and discover things for themselves.

And these discoveries will start with critical points on which they can further build: World War II, the Holocaust, Stalin’s persecutions.

Do you see yourself as an author of historical novels?

The thing is that I have never seen myself as an author of ‘historical novels.’ My ‘historical novels’ are rather a game, a make-believe, an experiment, a test.

I didn't set out to verbalize the fundamentals of a Ukrainian identity or anything along those lines. I used history more as a decoration, as a background. I was primarily concerned with the people, the characters, the images, the cross-sections of their mentality, the paradoxes of relationships, and the fluidity of emotions. About the language and the life in the language.

The most important thing is to believe in your characters, to feel them next to you, to become them. When I write, I transform myself into my characters and start thinking and feeling like them.

For me, writing is an ongoing effort to capture the essence of humanity, of what makes people human. And it’s not just about good things. The urge of violence, temptation are also what makes people human.

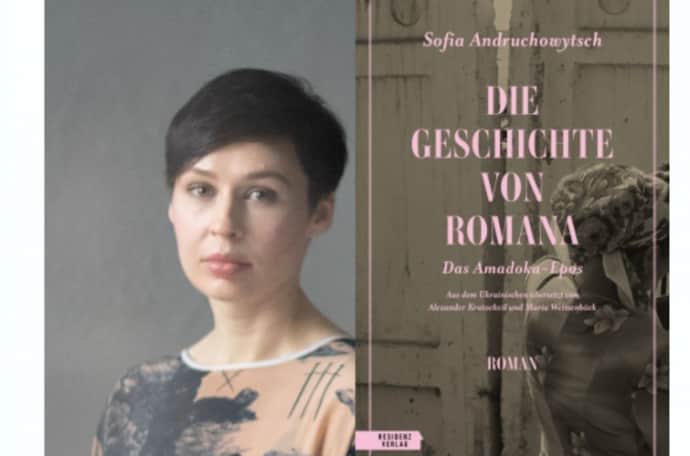

Sofiia Andrukhovych and the cover of the German translation of the first part of the novel "Amadoka", published by Residenz Verlag, 2023

At the same time, it was my attempt to get closer to what seemed impossible before. Was there a real war? Did people really torture, rape, and kill other people? How could one live under these circumstances? What could everyday life, encounters, dialogs, and street scenes look like?

I felt the need to share their suffering, fears, and losses and to take on some of those experiences, at least in my own imagination. That would have been my atonement as someone fortunate enough to live in different circumstances (as I thought at the time). On the other hand, the war in the Donbas made Amadoka even more urgent. ‘Different circumstances’ quickly became the same. By its sheer scope and multidimensionality, Amadoka helped me get several important closures at once, including working with historical material—at least for a while, because I can’t promise that I won’t do it again someday.

As an author, I would not be interested in continuing to work on other texts similar to Felix Austria [the novel published in 2014, set in the town of Stanislaviv in the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries,—ed.] or Amadoka since that would be too easy, too predictable, too boring. I must search for something else inside me.

With these experiments, there’s always a risk that you'll disappoint your readers. That's what happened with Amadoka, which followed Felix Austria. It will happen now, too. But you can't try new routes any other way.

Croatian and Ukrainian versions of the novel "Amadoka".

Photo: The Old Lion Publishing House

"The war has made me even more of a writer."

I wonder if the war changed you and your writing and your attitude toward literature.

Of course, it did. It’s been difficult to track these changes, but I can already make a certain ‘diagnosis.’

War is an extreme manifestation of reality, indeed. We often treat it as something abnormal and no longer see that war is actually a manifestation of being human and of human life. During war, all manifestations—good and bad—are still there. They only multiply and become much more pronounced.

As for me personally, I acquired certain skills that I simply could not make myself master before. But the need to act left me no choice.

This is an experience we all go through. My personal changes have a tiny scale compared to many other people, such as Andriy Liubka, who have been truly reborn and have taken on new incarnations. We all know so many names of people who have started to live a completely different life.

The first essay I wrote since the full-scale invasion began has this sentence: "I don’t know if I'll still be a writer after the war." But I am still a writer. As soon as I wrote that, I was still a writer, and I've become even more so.

The war didn't change me as much as it reinforced everything I had in me. On the one hand, I'm deeply frustrated by what I'm doing because this activity is not saving lives here and now. But on the other hand, I've come to an even deeper realization that I can't do more than I’m capable of. And okay, let it be words—I'll just focus on them.

So I've expanded my boundaries, my abilities: to communicate with other people, to go outside, to overcome my fear, to express myself verbally and in writing. I now have more courage to speak out—and not just for myself, but for my people and my country. It sounds dramatic, but this is our common experience: the selfishness of each individual has proven to be very useful for the common cause.

But therein lies a paradox: for the sake of the common cause, many people had to put their selfishness aside...

Selfishness has actually become a source. Altruism and self-sacrifice often result from narcissism. But it is crucial to put this narcissism and selfishness in the service of something good. In the service of the common cause and not of a particular person. Then everything works well.

We don’t have to deny narcissism—we just have to use it for broader purposes. I think a lot of things in the current war build on that and hold on to that.

And has your writing changed?

When it comes to the methods of writing, I have this sense of expansiveness that seems to give great hope as if we've all pushed through into the realms that were once inaccessible. But that's a terrible pushing—through the losses that can never be recovered. And that leads to total confusion: where do we go from here?

After the full-scale invasion began, I personally discovered the genre of an essay as an attempt to reflect on what I now see, hear, and experience.

The essay offers a multitude of possibilities. It allows you to write about the here and now. It can be more or less literary; it allows for fantasy and literary devices but also for sparseness and a clear rendering of reality. The essay gives a writer the space to reflect as much as they want, ask questions, and present those questions and answers at a variety of sharp and blunt angles.

In the essay, an event becomes a pretext to name the unnamed: complex emotions, borderline experiences, losses, existence after nonexistence and despite nonexistence. That is why this genre is now possible: through uncertainty and probing, it allows you to outline the unrecognizable reality with words and concepts; to reclaim it.

The essay has more plasticity than other genres and can emerge simultaneously with reality, while short stories or novels require more clarity and a greater distance. But even these attempts at definition are very conditional, for experimentation in creativity and art is valuable precisely because of its deviation from rules and transgression of boundaries.

In any case, I know that many Ukrainian writers have had the experience of being temporarily unable to write fiction, while essays have given them a chance to mirror reality.

This saved me right at the beginning and determined my activity and way of life in wartime. The invitations from the West and the interest of Europeans in Ukraine were also in line with this.

Thus, all these days merged for me into a continuous flow of travel, conversations, attempts to explain, meetings with people, and the feeling of exchange of opinions, energy, compassion, and empathy….

The essays are also my response to the outside demand. Since the outbreak of the all-out war, foreign media have shown great interest in the texts describing Ukrainian reality and its various dimensions. My texts have also tried to do that. I wrote them mainly for the Polish Dwutygodnik, but many of them have been translated into other languages and published in many other countries.

Finally, the editor of Bayard, a French publishing house, suggested that I put together a collection of essays that I had written since the beginning of the full-scale invasion and publish them in France, and I agreed. I believe that it is important to remind people about us and to talk about ourselves, to describe ourselves in our own words, to create and fill out our own image. We need to take care of our own presence in the world in every way possible. This reflection testifies to our place, our agency, our existence.

This collection of essays, entitled All That Is Human, will be published in France in a few weeks. And I think it's important that it will become another reason to talk about Ukraine and remind people of what we have to go through and what has become of our lives.

It's a reason for foreign readers to remember Ukraine and not to turn away from it.

The cover of the book of essays by Sofiia Andrukhovych "Everything human", France, Bayard Publishing, 2023

Will this collection be published in Ukraine?

At the moment, I do not plan to publish these texts as a book in Ukraine because I don’t feel it is necessary. We are so saturated with the experience of war; we have become so much this war that I think another book about war is just not needed.

I sense, however, that the demand for fiction is growing. We desperately need symbols, metaphors, myths, and fairy tales; we need other realities, other languages and images to become like an embrace, a restful dream that heals wounds.

The greater the pain, the more carefully we should talk about it. But at the same time, we need to talk about it. And fiction and make-believe, games and lullabies can help us do that.

Are you working on a fictional book yourself right now?

My lifestyle has changed drastically in the last two years, and it’s now much harder to find the time to do my main job. I could have never written Amadoka the way I live now.

This lifestyle also affects the way I write. I do research and write, but I’m still reluctant to share more at this point.

Today, each of us has an incredibly complicated task. The task of a Ukrainian writer is to write about the war without talking about it. To talk about the war without mentioning it. To talk about all sorts of things in the world, but not about the war. Meanwhile, it is completely impossible to avoid the war because it has turned everything into itself and connected everything with itself.

War permeates our reality today, and we should acknowledge that and write about it. And we should also write that we are all kinds of things, but not war.

"You need to love your neurosis."

We have briefly talked about how Ukraine tells the world about itself. Let’s dive deeper now. How do people in Europe react to what you tell them? Do they feel compassion and understanding or perhaps weariness?

I mostly talk to people who are interested in literature, read a lot, or are involved in culture. The conversations with them somehow always feel more pleasant and meaningful because these people have a much broader understanding. So, my conversations about Ukraine and what is happening here and now have not been traumatic.

It’s a new, strange experience when you suddenly become a kind of confessor to Europeans: With a guilty look, they confess about their own—often critically scrutinized— sentiments to the ‘great Russian culture.’ Just recently, I had such a session with one of France's best-known contemporary writers. He regretted that Russian literature was one of many sources that had influenced his formation. He admitted that he partly blamed himself.

Honestly, I did not know what to say to him. I don’t think I have the right to blame other people for their tastes, inclinations, or feelings. The idea that Russian culture is in many ways closely related to Russian imperialism, while absolutely true, often develops into something destructive. It gets oversimplified.

I don’t think anyone should apologize for the very fact of reading Dostoevsky. It's important to reshape the attitude toward this culture and its ‘absolute greatness’ that prevailed until recently. To look at it from a different angle and see all the other cultures that were oppressed by the Russian culture and understand why this happened.

There is an enduring sense of curiosity about us—I am 100% sure of that. During the first year of the all-out war, in France, in Germany, in Austria, I had the impression of a general shock when, you know, people would look at me with wide eyes and say, "I can’t believe I didn't know about this country and these people you’re talking about, about all these writers and this culture. How did that happen? It’s like a huge continent that we haven't even noticed until now." That's the impression I get most often.

Even now?

It has mellowed by now. Today, people know much more about Ukraine. The shock is over.

The shock of realizing their great ignorance?

Yes. Now, there is a feeling that people are more knowledgeable and have more specific interests. They can express their opinions. Because the more you learn about something, the more details and shades emerge, and the subject is no longer black and white, hard-and-fast, or dramatic.

Of course, there's also fatigue. It’s hard to stay intensely interested when this isn't directly affecting your life, when you're not losing your home and loved ones, when your friends and relatives aren't under constant threat. You may even feel a little bored.

However, I have also come to realize (naive as it may sound) what words and literature can do to overcome this fatigue and boredom. Fiction and art touch many points of consciousness and subconsciousness simultaneously because they entertain and because they are multidimensional and approach everything—human feelings, stories, facts, interpretations, reflections—from different angles.

Unlike news, which is too monotonous and really tiring. News has a high level of tension, and that tension wears you down and repels you. So when people can't take the news anymore, there's still the possibility of reminding them of the complicated things through art. That's only a tiny part of the role creativity plays, but it’s enough to make you feel that what you're doing has meaning.

Do you see much Ukrainian art abroad?

Sometimes, I have the impression that Ukraine is literally everywhere abroad. Wherever you go, you meet Ukrainians, hear the Ukrainian language, and hear Russian spoken by people from Ukraine. People often share their stories related to Ukraine with me and describe the events they've attended that are dedicated to Ukraine, as I'm seen as a representative of the country.

However, it is important to understand that this impression of a complete overhaul, a total presence in the cultural and information spaces is false. Old habits, old beliefs are incredibly strong, and Russian propaganda is still active. But we must make full use of the channel that is now open; we must take our rightful place.

There’s another issue I want to discuss. How often do you have to deal with Russians on your trips abroad? I ask this because people who don’t often have the chance to go abroad might get the impression that all they do there is force Ukrainians to debate and collaborate on projects with Russians and equate our experiences and voices. And it looks like people there don't quite understand that this equality is impossible and unethical. They don’t understand that Russian voices will inherently be more understandable and louder as the voices of an empire compared to the voices of its (albeit former) colonies.

A few times, I was invited to participate in festivals or events where Russians were also involved. I refused. I tried to explain my refusal rationally, saying that it was a continuation of the same imperial discourse and that experiences cannot be equated, but to each of my arguments, I received a counter-argument, the logic of which, frankly, I did understand. But what about understanding when my feelings didn’t match with it.

So when I was invited to a discussion in Berlin, in which Russian authors were also invited to participate, I decided to stop engaging in logical arguments. I replied that for every Ukrainian (no matter how anti-war and anti-Putin the Russian participants were), this form of participation felt deeply traumatic and emotionally impossible as long as the war raged and people were being killed.

My response was naive and simplistic, but unexpectedly, the organizers responded with an apology for their invitation. I had the feeling that they understood and respected a refusal like this. Then I thought that we tried too desperately to rationalize these things, neglecting the importance of feelings.

I don’t like that now I have to step out of my comfort zone and study each agenda carefully to avoid ending up in an unpleasant company.

This is a manifestation of our social neurosis, which is, of course, a natural reaction to an extremely painful abnormal situation. But we've become terribly neurotic about it—instead of focusing on what we're communicating personally, what we're producing, we're spending our energy on entirely different things.

Irrational things are very convincing and should elicit respect. And they should suffice. But for people, for Europeans who have no experience of living on the border between life and death, under constant threat, irrational reasons are not enough.

It’s just that the Russians have their own story. I wish they would deal with their story themselves so that Ukrainians would not be expected to help Russians deal with their feelings of guilt—‘good Russians’, I mean.

Personally, I know for sure that I cannot have these conversations now and for a while because they are simply pointless. But on the other hand, no one can forbid the Russians to feel and to do what they do—to search for their own formulas and answers, to talk, to reflect, and to help in whatever way. They absolutely have this right.

Neither do I think that I can judge my Ukrainian colleagues who do see some point in those conversations. I can have certain feelings about it, but I don’t think I should interfere in any way. I mean, I would be more relaxed about the situation. I am saddened by this neurosis that leads to the total condemnation of people engaging in discussions with Russians.

Perhaps they know what to say and how to say it so that it is clearly articulated. Maybe in these discussions, they really show our opinions from different angles. It’s not necessarily about reconciliation. Maybe these dialogs should be used as an opportunity to raise awareness. This possibility should exist, at least theoretically, if we’re talking about freedom.

But then it comes down to the personal skills and competencies of each speaker. I know that I can't articulate myself that well, I can't argue, I can't be sharp in discussions. So I'm not going to engage in that.

However, I believe there are people out there who can spell everything out, detect manipulation, and express themselves in a way that makes Russian opinion sound unconvincing. I mean, they can dismantle it or kind of deconstruct it.

So how should we overcome our neurosis regarding dialogs with ‘good Russians’?

Let me try to explain the danger of engaging in conversations with ‘good Russians,’ which our Western colleagues do not understand. Such conversations give the appearance of some sort of mutual understanding and lead to the following conclusion: you see, people of culture have gotten along with each other. This means that we are all human beings and that we all strive for the good. In turn, it means that even in the political realm and in the realm of war, we can just sit down at the negotiating table and reach an agreement. Making concessions and compromises is what they expect of us. That is why this step is dangerous.

So we just have to be extra careful. Because we cannot engage in conciliatory conversations while the war is raging. That is the simplest thing we have been trying to explain from the very beginning. Don't expect that from us while the war is going on and people are being killed. Let’s talk about it later; it's not the most urgent thing right now; just leave us alone and please do something more useful.

So, when it comes to neurosis and how to overcome it—I don’t think it’s possible to overcome it. It's too pervasive; it's society’s reaction to abnormality. We could talk a lot about psychology, about feelings that need to find an outlet in this way. About how to get a grip on yourself (as far as that's possible with personal trauma): do I really need to express myself at this particular moment or will I hurt other people or the situation?

We could also say that, after all, the war is being fought for exactly this—for Ukrainians to be able to express all kinds of opinions. It’s all about freedom of feelings and expression. It’s just that it is every person’s business.

Maybe we should just let this neurosis stand. Maybe it is compensating for something much more terrible. Maybe it’s not the worst thing that's happening to us.

Just to put things into perspective. In Poland, a scandal has erupted these days due to the public reaction to Agnieszka Holland’s film "The Green Border." The very fact that the film has triggered such a strong reaction means that it has hit a sore spot. It means that it tells the truth. And this truth is so unbearable for many Poles that it provokes aggression.

If we compare the outbursts of aggression in Ukrainian society, triggered by the condemnation of actions or words of a public figure, with similar aggression in Polish society, we’ll see that in Ukraine it takes a much gentler form and is limited to verbal aggression in social media. As we know, Agnieszka Holland had to ask for 24/7 security protection and can hardly leave her house—so real is the physical threat she faces from Polish citizens affected by her work. Olga Tokarczuk had a similar experience when her novel, The Books of Jacob, was published. Maybe I’m wrong, but I have the impression that Ukrainians are much more tolerant—even in times of war.

That sounds optimistic.

In fact, we need to love our neurosis.