Ukrainians in Quebec struggle to learn French before their work permits run out

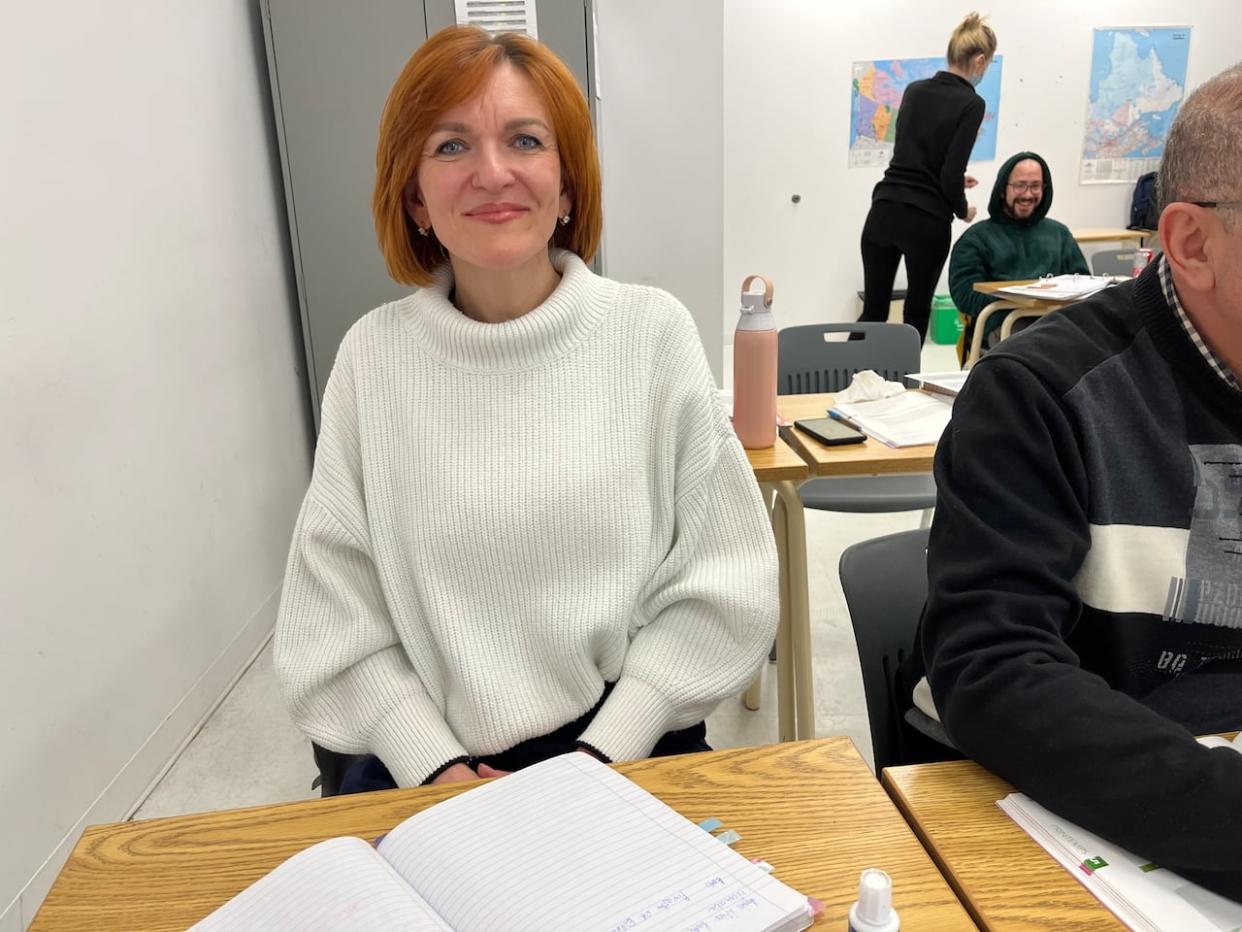

Ivanna Shapirko wants to be a Quebecer.

When she fled her war-torn home country of Ukraine after Russian forces invaded, she had the option to move anywhere in Canada. She chose Montreal.

As a child, she had dreamed of learning French. Now, despite the chaos of war, an opportunity had presented itself.

"I said 'okay, I can be safe here, I can rebuild my future here if I cannot go back to Ukraine,'" she said in a recent interview. "I'm going also to fulfil my dream of learning French. … This will give me, even though it's for a bad reason, a good opportunity to leave."

But Quebec's permanent residency requirements, which include French proficiency tests and two years of work experience in a qualified position, could prevent Shapirko and other Ukrainians from settling here long term.

Olena Martynova moved her family to Calgary because the permanent residency requirements for Quebec were too difficult for her and her husband to attain. (Courtesy of Olena Martynova)

Shapirko has been taking government-offered francization courses for nearly a year. They're working. When speaking English, her brain sometimes reverts to French. Learning the language is important to her. She wants to integrate into Quebec society.

But she hasn't been able to work during that time because the courses take up so much of her time.

That leaves her in a tricky situation. To to get a Quebec selection certificate — an acknowledgment that Quebec will accept her as a permanent resident, allowing her to request permanent residency from the federal government, she has to be proficient in French. She's getting close, thanks to the courses — she finishes in April.

She also needs two years of work experience in a job that requires some kind of specialized training or education.

She, like other Ukrainians who came to Canada after the war, currently has a three-year work permit, not long enough to attend language courses in Quebec and subsequently gain the necessary work experience.

The federal government does allow Ukrainians to extend their temporary resident status, but that deadline for them to apply is just a few weeks away — March 31. A spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada said Canada is "dedicated in its support of those affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine."

Shapirko wants to remain in Quebec, but she knows other Ukrainians who have found easier paths to permanent residency in other provinces.

"It's a moral dilemma because Quebec has really received me with open arms. People are marvellous. There's lots of support that was available," she said.

"I would like to give back now by [staying] here, by working here, by integrating into society, but I'm inadvertently punished."

The challenge of balancing French courses with working was too much for Olena Martynova and her husband. Martynova, 35, is from Kharkiv, Ukraine and initially came to Montreal when she fled advancing Russian forces.

Michael Schwec, the president of the Quebec chapter of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, says Ukrainians are embracing the challenge of integrating into Canadian society. (Paula Dayan-Perez/CBC)

She said that she and her husband would not both have been able to learn French while working to support their two children.

"Arriving in a new place is very difficult for an immigrant. You have to learn new things, get settled and earn enough money to live," she said in an interview from Calgary, where she lives now and where permanent residency requirements are less strict.

"Often, one person learns the language and the other one has to work."

In a statement, a spokesperson for the Quebec Immigration Ministry said there are no current plans for Quebec to change its requirements for issuing a certificate of selection, the requirement Ukrainians need to apply for permanent residency in Canada.

Michael Schwec, the president of the Quebec chapter of the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, said he hopes various levels of government will exercise flexibility with their permanent residency requirements for the Ukrainians who fled the war.

"The people who are coming from Ukraine during wartime to Montreal, they're welcoming the challenge to learn French, to get the kinds of jobs they need to meet the criteria, to get permanent residency," he said. "They want to succeed."

Most of them are women whose husbands are still in Ukraine, he said. Stringent permanent residency requirements and the looming deadline of expiring work permits is adding layers of stress to their lives, he said, even as they worry about the fate of their country while struggling to support children in a new environment.

That burden weighs heavily on Alena Shykova, a Ukrainian woman from Kharkiv, who left the country and came to Canada in August 2022. She has a network of friends who have helped her adapt to her new surroundings, but she misses home.

Her husband is still in Ukraine, working in Kyiv, but he could be called upon at any time to head to the front lines. Shykova doesn't know what he'll do if that call comes.

"It will be his choice," she said, pausing. "But it's OK … you know in the beginning I thought it was wrong, and I felt guilty leaving my country."

Shykova shed that guilt in a bomb shelter after she endured air raid sirens to bring her sick son to a hospital.

"In that shelter, I felt that it was wrong for my child to stay in this country because if you are able to save children you should evacuate them to a safer place," she said.

She and other Ukrainians in Canada say they have been welcomed with open arms. They hope to be able to stay without the additional stress of permanent residency requirements.

But they still miss home.

"Every time I hear a song of my childhood," Shykova said. "I think of that place and I start to cry."