UNC arts school grad says leaders knew violinist molested her, let him keep teaching

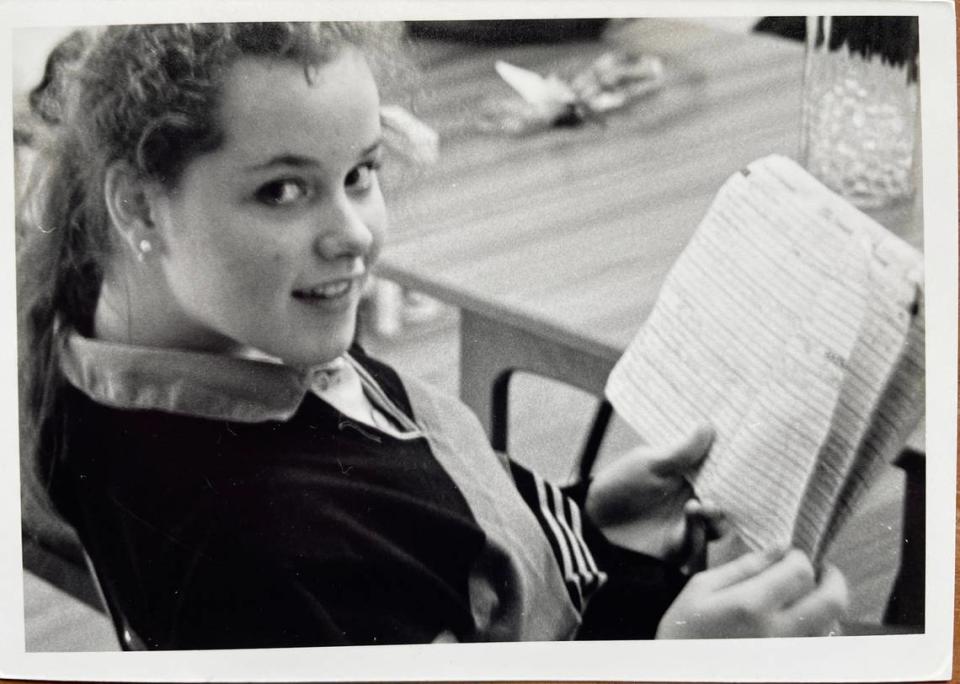

In May 1988, a 17-year-old girl told her sister a secret.

Her violin teacher was using his taxpayer-funded studio to have sex with her during what should have been private lessons at North Carolina’s prestigious public conservatory, Lisamarie Vana claimed.

While Vana insisted the trysts were consensual, her older sister saw abuse instead. Resolving to put an end to it, she told their mother.

That summer, Vana overheard her mother calling violinist Stephen Shipps in a voice so hostile she left the room. Her mother told her she’d also complained to administrators at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, Vana said.

But it wasn’t until 34 years later that a judge sentenced Shipps, now 69, to five years in prison for sexually abusing another underage student. Vana attended the sentencing, with her sister and two friends, in hope of some closure.

After being criminally charged for the first time, Shipps has admitted to trafficking another student while on the University of Michigan’s music faculty, taking her across state lines to have sex with her in 2002.

In a sentencing memo, federal authorities shared evidence that Shipps abused girls before and during his time as a UNCSA faculty member in Winston-Salem from 1980 to 1989.

Proving what UNC arts campus leaders knew and did about Shipps while he was on faculty is difficult, in part due to the passage of time and in part due to limited records from the School of the Arts.

But in lawsuits and correspondence with federal prosecutors, former students say UNCSA officials knew about allegations against Shipps and could have prevented what federal authorities say was decades of molestation by reporting him to off-campus authorities.

Instead, they allege, campus leaders sacrificed girls’ safety to preserve an elite school’s reputation.

UNCSA is still grappling with the lawsuit, which is pending in state court.

“Simply stated, we are horrified by the allegations of sexual abuse and are appalled by the concept that sexual abuse could happen under the guise of artistic training,” Chancellor Brian Cole wrote in response to the lawsuit. “We recognize that the words here are only a start — it is our actions that will most clearly communicate the strength of our commitment.”

A buried story

As a teenager, Vana defended Shipps, insisting that the relationship was consensual.

“The grooming process was so complete that I didn’t even know I was being abused,” Vana told The Charlotte Observer.

It wasn’t until Shipps’ 2020 arrest that Vana told her story differently to federal authorities who were researching a pattern of abuse by Shipps. Soon after that she became one of 56 alumni suing UNCSA for, they allege, allowing them to be sexually abused by Shipps and many others. Of the accused, only Shipps has been convicted in criminal court.

She’d won a high school scholarship to study violin there in 1986, and spent her first months there absorbing rumors that Shipps had sex with his female students, Vana told the Observer.

While he taught Vana violin throughout her time at UNCSA, she said he suddenly took her under his wing in her senior year, when she turned 17.

When Vana was scheduled to play with the Winston-Salem Symphony, Shipps — then the symphony’s concertmaster — invited her to stay at his home while campus closed for spring break 1988, she alleges in her complaint.

Vana said she’d never had sex before that week. But Shipps coerced her to do so with him while his wife was in another room, according to the lawsuit. From then on, he invited her to his office “on a daily basis” for sex, she alleges.

“His teaching was only about himself and his own sexual gratification,” Vana told the Observer.

Vana also accused Shipps of pimping her out to a colleague across state lines. The pair convinced her to fly to Wisconsin to take lessons and shop for violins, one of them even paying for her ticket, she alleged in the lawsuit.

But when she arrived and refused that man’s attempts at seduction, Vana said in the lawsuit, he drugged and raped her throughout the weekend.

The teacher, now deceased, told Vana that Shipps had slept with his wife, and sent her to him as an “appeasement offering,” she wrote in her complaint.

The ‘punishment office’

People suing UNCSA are not the only ones who say many on campus in the 1980s knew about Shipps’ alleged behavior. Other former students say they recall just one attempt to curb it before his departure in 1989.

When UNCSA violin graduate George Carter, who is not suing the school, learned in November 2020 that federal prosecutors had charged Shipps, he rushed to tell them of his time at UNCSA.

Also a violin student, Carter arrived in 1984 to a campus saturated with rumors that Shipps sexually abused his female students, he wrote in an email to prosecutors.

Another student told Carter that Shipps sexually harassed and assaulted her, he wrote in an email to federal prosecutors. By 1986 it was “common knowledge” that Shipps had a sexual relationship with her and at least one other student, Carter said.

Two years later Shipps moved from his secluded music department studio to a smaller office in a different building, Vana said.

Carter recalls that the new studio had long windows exposing the interior to a busy hallway. Students understood the “punishment office” was music dean Larry Alan Smith’s attempt to curb further abuse, Carter said. Even among his new neighbors, Shipps was the only one forbidden from closing the blinds, Carter wrote to prosecutors.

When Carter visited campus the year after Shipps’ 1989 departure, he noticed that a new violin teacher’s studio had been returned to the more private location, across the hall from the other violin professor’s.

“This could have all ended in 1986 if (Smith) had taken the appropriate actions,” Carter wrote prosecutors in an email.

Smith, also a defendant in the pending lawsuit against UNCSA, stepped down from his position as music dean the year after Shipps’ departure. He has not responded to several requests for comment. Then-chancellor Jane Milley left her position in 1989. Milley, too, is named as a defendant in the lawsuit and hasn’t responded to requests for comment.

But Vana said the change of scenery did little to stop Shipps from molesting her.

“It was safe if it was dimly lit,” Vana said of the second studio. “If he wanted servicing, he would dim the light.”

Alumna Stephanie Silverman, who joined Vana at the sentencing, remembers Shipps’ move across campus during her 1980s enrollment, saying it made no sense for him to be so far from her own violin teacher in the main music wing.

“We knew what was going on,” Silverman said. “They didn’t do it to anyone else.”

UNCSA said officials have found no records to verify the office locations.

Passing the trash?

Another plaintiff who accuses Shipps of sexual abuse was a few years ahead of Vana. Students gossiped about Shipps during her time on campus, the older alum said.

Unlike Vana, she spoke anonymously. The Observer doesn’t name victims of alleged sexual assault without their consent.

“Steve has had the reputation of fooling around with his students in the past,” she wrote in a 1980s journal entry she provided to The Observer.

Shipps warned her to keep quiet about his sexual contact with her, saying he’d been in trouble with the UNCSA administration for similar behavior, the woman told the Observer.

“The things that would happen if we were found out would be: he would probably be fired but first, I would be thrown out of school,” she wrote in another diary entry. “I would sort of be blacklisted, he would have a lot of reason to hate me since it would probably be my fault that we were found out, he might have a hard time finding another job, etc.”

But Shipps found another job barely a year after Vana’s mother, now deceased, reported him to the school, the lawsuit claims.

“To protect UNCSA’s reputation, Shipps was simply allowed to leave UNCSA and go to the University of Michigan,” the lawsuit alleges. Another plaintiff contends that Shipps’ colleagues wrote recommendations.

Inaction against a suspected child sex abuser is truly dangerous, said Mike McDonnell, a spokesperson for the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, whose members saw much of that over decades.

“You’re essentially just saying that it’s OK for someone else,” McDonnell said. “It gives this abuser a whole new group of potential victims… just because you don’t know these kids’ names and faces doesn’t mean abuse stops.”

Seeking the truth

As a public school in the 1980s, UNCSA was required to report even suspicions of child abuse to the Forsyth County director of social services. But even if they did, the county office wouldn’t have any relevant records in its online system, an employee said. Any surviving documents would only be available if subpoenaed, she said.

While North Carolina state law forbade sexual relationships between underage students and their teachers in the 1980s, UNC policy wouldn’t provide additional restrictions until the mid-1990s. That was spurred by a rare, until now, public accusation of sexual abuse at the School of The Arts.

There is a document that captures allegations against Shipps at UNCSA, six years after his 1989 departure.

In 1995, an alum sued UNCSA, saying administrators were aware that two dance teachers sexually abused him in 1984 but failed to help him. Before his case was dismissed due to the state statute of limitations, the arts campus’s Board of Trustees responded by launching an investigation.

That included establishing a hotline where callers could report abuse and inappropriate behavior by campus faculty and staff.

A document obtained independently from a state archive revealed that eight people told hotline workers that Shipps had sexual relationships with students, including one first-hand report from a victim who described him harassing her.

UNCSA did not have a copy of that document until The Observer and the N&O uncovered it in 2021, and has no record of investigating Shipps, school attorney David Harrison has said.

During a brief phone conversation with the Observer last year, Shipps declined to discuss the 1995 hotline complaints against him. Neither he nor his lawyer have responded to multiple requests for comment since his sentencing. But five of the teachers accused alongside him claimed to have no knowledge of allegations against them when contacted by a reporter in 2021, suggesting there may have been no follow through.

Some still worked with UNCSA; others were teaching young students elsewhere.

Multiple Shipps accusers

Among the 56 former students suing the School of the Arts, three name Shipps as a defendant. Others describe disturbing behavior and rumors about him.

In 1980, the year Shipps joined UNCSA, one plaintiff auditioned for him, the lawsuit says. Shipps told her that he’d accept her only if he could have a chance to date her, she said in her complaint.

After she enrolled at UNCSA at age 16, Shipps had her move into his home for a month, she alleged in the lawsuit, ostensibly to catch her up on private lessons.

But on her first night at the teacher’s home, the girl woke up to Shipps fondling her. He stripped and raped her, the lawsuit states, later promoting her to a violin position she hadn’t earned.

The plaintiff endured Shipps’ groping until the year’s end, when he stopped giving her lessons, according to the lawsuit, a punishment for refusing to have sex with him.

She says in the lawsuit that she complained to then-music dean Robert Hickok, who has since died. When Shipps next called her to his office, it wasn’t to resume teaching.

Then in his 20s, Shipps threw chairs, pushed his student against a wall and threatened to slap her for going to the dean, she wrote in her complaint. He screamed at her, telling her that her days at UNCSA were numbered.

Shipps did eventually kick her out of the program, she said, but the school allowed her to re-audition and study under another professor.

She didn’t recount any memories of Shipps being punished.