His uncle pioneered organ replacement. A Milford rep carries on that legacy

Nowadays, becoming a hero in Massachusetts is as easy as checking a box on a driver’s license application - one quick mark in the organ donor field on the form and voila! Instant hero.

But it wasn’t always that easy.

When Nobel Prize recipient Dr. Joseph Edward Murray, a native of Milford, became a doctor, organ replacement was more of a science fiction fantasy than an accepted and often-practiced procedure.

“But for his perseverance and talent, we wouldn’t be where we are today,” said state Rep. Brian Murray, D-Milford, the doctor’s nephew. “My Uncle Joe pioneered this field.”

Archives: Transplant doctor, Nobel winner and Milford native Murray dies

State residents urged to sign up for organ donation

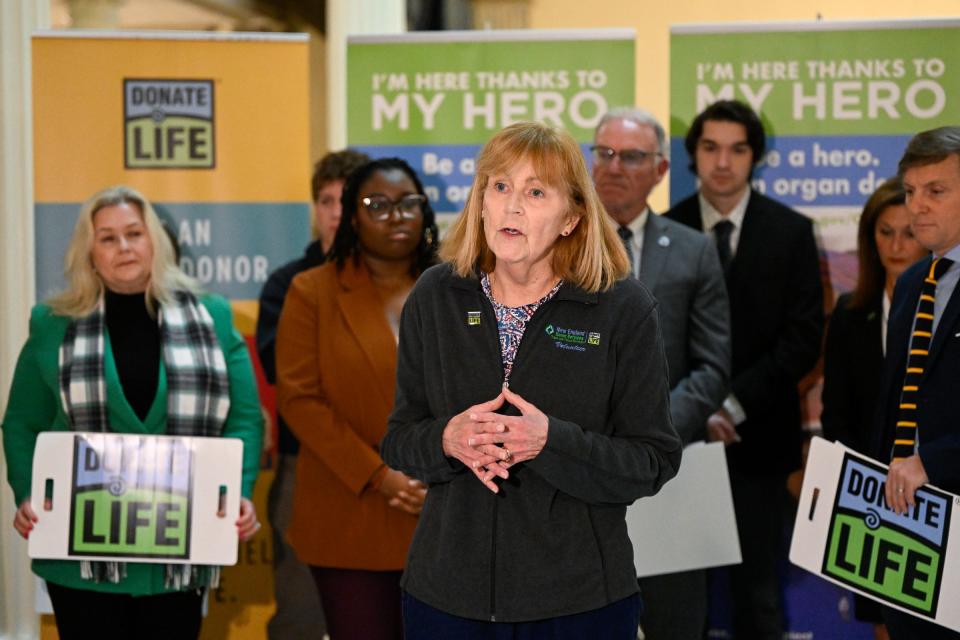

The state representative who was elected in 2016 and now serves in the same seat once held by his grandfather is the host of Organ Donation Day on Beacon Hill. The day is geared to encourage state residents to check that box when applying for or renewing a driver’s license. Motorists can also log into the Registry of Motor Vehicles website and check the box virtually, regardless of license status.

The state plays an important role in the donation process, as the vast majority of individuals in Massachusetts who register as organ and tissue donors do so at the state Registry of Motor Vehicles, according to New England Donor Services Chairman James Arciero.

“In 2022 in New England 1,325 lives were saved by organ donation, a 7.9% increase from 2021 because of the generosity of individuals who became organ donors,” Arciero said, adding that thousands more lives were enhanced through the gift of tissue donation. “With the need for life-saving transplants growing every day ‒ over 106,000 patients are now on the U.S. transplant wait list ‒ it is crucial to educate our communities about taking action to register as donors.”

Look at license, find red heart

Alexandra Glazier, CEO of New England Donor Services, described organ donation as a “lifesaving gift.” More than 1,000 New England residents received that gift in 2022 from 255 deceased donors.

Several area residents whose lives were touched by donation gathered with the state lawmakers and shared their stories.

Peter Bodenstab, 37, a marketing manager with John Hancock, received a liver when he was 3.

“I have lived 34 healthy years since,” Bodenstab said.

Making a difference even in death

Eileen Sullivan, of West Roxbury, who learned she suffered pulmonary fibrosis, usually a disease developed by middle-aged men, received a lung after the birth of her daughter. She gave birth to a healthy boy two years later, the first child worldwide born to a lung recipient. Sullivan received a second lung transplant in 1997, after an infection precipitated her body’s rejection of the first one.

Bob Canfield of Hudson donated the organs and tissues of his wife, Suellen, after she suffered a brain aneurysm.

“The outlook (for her recovery) was bleak,” Canfield said. He remembered they had discussed donation “and I knew what she wanted. It was when the nurse asked if I wanted to donate that I was reminded of the conversation.”

In the end, Suellen’s corneas, kidneys, liver, pancreas, skin and heart valves went to help many people. Canfield said he received a letter from the recipient of his wife’s liver.

“In the letter he thanked us,” Canfield said.

Sullivan also never forgot the gift she received.

“I never lost sight that two families said yes,” Sullivan said.

Obstacles included legal, moral and ethical questions

When Dr. Joseph Edward Murray was first working in the field in the 1940s and 1950s, he faced significant opposition from medical experts, said his nephew. One of the big debates was whether it was ethical to remove a functioning kidney from a donor to transplant it into another human. And could someone consent to having the procedure?

“The first precept in medicine is to do no harm,” said Brian Murray. “My uncle had to show that the procedure would do no harm.”

To that end he consulted with legal experts and religious leaders to prove he was “not playing God. There were many obstacles to overcome.”

The doctor became interested in organ replacement while working with World War II combat soldiers while he was stationed at the Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania. A burn case informed his work; he learned that transplanted tissue that closely matched a patient’s genetics survived longer than unrelated tissue.

In 1954, Murray performed the first successful human kidney transplant procedure on identical twins, with one twin donating a healthy kidney to his ailing twin. The recipient lived for eight years following the procedure, marrying and fathering two children, before he died of causes unrelated to the surgery.

“To ensure the twins were identical, my uncle took them down to the West Roxbury police station and had them fingerprinted,” Brian Murray said, explaining that when the prints matched, the doctor was assured that the men shared the same genetic material. He performed the operation, which was a success.

“That’s how the story broke,” he said. “Beat reporters who were hanging around the police station wanted to know what was going on - they broke the story.”

Brian Murray described his uncle as a “very caring, compassionate individual who was concerned with the plight of others. He had a peaceful and serene approach and had a calming effect.”

Worked as physician his whole life

Brian Murray was serving on the Milford School Committee when his uncle was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1990.

“I worked with Joe closely on the commemorative events planned in Milford,” he said.

Murray, who died in 2012, was a practicing doctor treating patients his whole life, said his nephew.

At a meeting with a large group of Nobel laureates, he was the only one who was still a practitioner in his field.

“A woman fell and hurt her ankle that meeting. The cry quickly went up for a doctor in the house,” Brian Murray said. “In that group of brilliant scientists, researchers, my uncle was the only doctor and he attended the injured woman.”

The Murray family has deep roots in the Worcester County community. Brian Murray’s grandfather, William A. Murray, was elected to serve in the Legislature in 1916. One hundred years later, Brian Murray was elected to the same seat. His father, also William, was an attorney and served in the Milford District Court.

Brian Murray said he learned that one of his uncle’s great disappointments was that his father had died a year before the successful kidney operation.

After decades working on organ transplantation and ways to mitigate rejection of the tissue, the doctor’s interests diverged. Murray went on to pioneer firsts in cranial facial reconstruction surgery.

“My uncle was like Ted Williams - he had a successful career as a hitter, but then imagine Williams switching after decades to becoming a pitcher and then being deemed the best pitcher in the field,” Murray said, explaining his uncle’s success. “Many people don’t understand the magnitude of his achievements.”

Attending U.S. Transplant Games inspired awe in doctor

In remarks that Murray prepared for a Harvard Medicine article in 2011, he discussed attending the 2004 U.S. Transplant Games, noting the “throngs of competitors,” and his awe at realizing that without the new organs inside, they would not be jumping, stretching, loosening up or getting ready to compete.

“I thought back to the day when it all began (50 years before). Ronald Herrick (the donor of that first kidney) and I were still here, but Richard Herrick (the recipient) and the rest of our team were gone,” Murray wrote. “So too were many of the recipients — including all those who died young despite our best efforts. They all understood, perhaps better than we, that life is precious and fragile, and often must be fought for. They went to their graves believing that if they were not going to make it, they might at least help us learn how to save someone else.

“How I wished that all of them — donors, recipients, doctors, nurses, scientists — could be standing there with us on the platform, watching the competitors playing on that sunny field of green,” Murray said.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Organ donation in Massachusetts: Lawmaker carries on uncle's legacy