How your uncle's conspiracy theories trigger your brain's anxiety areas

Perhaps you've been here this holiday season: A family member shares a political belief that is entirely the opposite of your own, and suddenly your blood is boiling. You either bite your tongue, and quietly fill with rage, or fire back with an impassioned rebuttal.

Neuroscientists say they now can track how this common experience unfolds in the brain.

When our political beliefs are challenged, our brains light up in areas that govern personal identity and emotional responses to threats, according to a study published Dec. 23 in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

SEE ALSO: This Chrome extension shows you how biased your social feed is

"Political beliefs are like religious beliefs, in the respect that both are part of who you are and important for the social circle to which you belong," Jonas Kaplan, the study's lead author and a psychological professor at the University of Southern California (USC)'s Brain and Creativity Institute, said in a news release.

"To consider an alternative view, you would have to consider an alternative version of yourself," Kaplan said.

Image: Anthony Behar/Sipa USA

The study offers a fresh perspective on how people respond to conflicting ideas — be they political opinions or the dubious contents of fake news stories — and could help us figure out how to have more constructive conversations during these divisive times, said Sarah Gimbel, a co-author and research scientist at the Brain and Creativity Institute.

"Understanding when and why people are likely to change their minds is an urgent objective," she said in a statement.

For the study, the neuroscientists recruited 40 self-declared liberals.

The team then used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. Sam Harris, a neuroscientist at Project Reason in Los Angeles, also worked on the study.

Researchers wanted to determine which brain networks would respond when someone's firmly held beliefs are challenged. So they compared whether and how much participants changed their minds on political and non-political issues when provided counter-evidence.

Image: Mark wilson/Getty Images

During their sessions, participants were presented with eight political statements that they said they agreed with, such as, "The laws regulating gun ownership in the United States should be made more restrictive," or that the U.S. should reduce funding for the military.

Participants were then shown five counter claims challenging each statement. Next, they rated the strength of their belief in the original statement on a scale of 1-7.

The neuroscientists studied participants' brain scans during these exercises to figure out which areas were the most engaged.

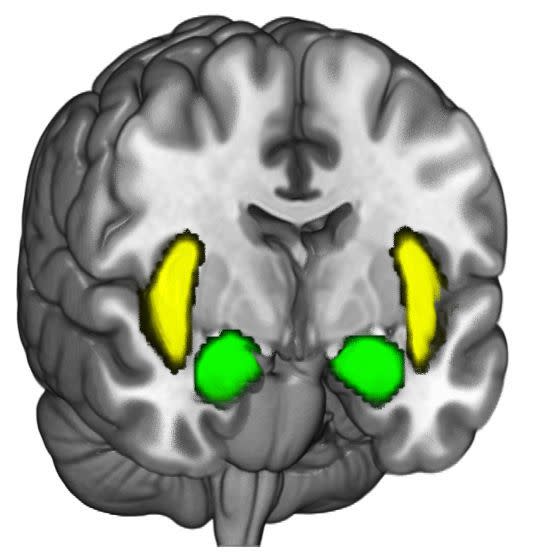

Researchers found that the brain's amygdala and insular cortex were more active in people who were most resistant to changing their beliefs. Both brain areas are important for emotion and decision-making and are associated with fear, anxiety, emotional responses and the perception of threat.

Image: Brain and Creativity Institute at USC

Participants' default mode networks — a system in the brain — also saw a spike in activity when people's political beliefs were challenged.

"These areas of the brain have been linked to thinking about who we are, and with the kind of rumination or deep thinking that takes us away from the here and now," Kaplan said.

But while people wouldn't budge on political topics like abortion or same-sex marriage, participants tended to cling less tightly to their beliefs on non-political topics.

For instance, participants' beliefs weakened by one or two points when they were shown counter evidence on statements such as whether "Thomas Edison invented the light bulb" or "Albert Einstein was the greatest physicist of the 20th century."

Brain activity in the amygdala and insular cortex was also less active when people were more willing to change their minds, the researchers found.

"I was surprised that people would doubt that Einstein was a great physicist, but this study showed that there are certain realms where we retain flexibility in our beliefs," Kaplan said.