Uncovering The Effects Of The Indian Relocation Act Of 1956

Native American women head to Los Angeles for job opportunities in 1956.

Throughout the United States’ complicated history, the stories of Native Americans have often been misrepresented and misunderstood in the cultural mainstream narrative — but groups today, such as the Red Road Project, are working to share Native American experiences as told by Indigenous peoples.

Since European colonizers first landed in North America, Native Americans were killed, lied to, and moved around, with Indigenous Americans being displaced from their own land. With the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the US government allowed European Americans and their descendants to take land from Indigenous peoples and forcibly move them to other areas. To try to avoid violence, President Ulysses S. Grant pursued a “Peace Policy” in 1868 with the goal of relocating tribes from their ancestral land to designated parcels. This resulted in many Native Americans being corralled and effectively forced to live on reservations.

A home on the Sioux reservation in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, on Feb. 28, 1956

By the 1950s, reservations were seen by the US government as too expensive. The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 attempted to move Native Americans to cities, but many struggled to adjust to this new life and faced hardships including discrimination and unemployment.

BuzzFeed News spoke with Hunkpapa Lakota artist Danielle SeeWalker and Italian photographer Carlotta Cardana, cofounders of the Red Road Project — an organization that documents Native American stories and history through words and visuals — about the effects of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956.

How did your involvement with this project start?

Danielle SeeWalker: We’ve been working on the Red Road Project since 2013 and it began as two friends chatting over a glass of wine, which led to deeper conversation about Native Americans being represented poorly in the media. Since that time, we have covered many topics and have done a lot of fieldwork in many various Native American communities from reservations to urban areas and everywhere in between. Now, we are focusing on the Indian Relocation Program as another subtopic of the overall project. We wanted to highlight some root causes and uncover the buried histories that brought so many Native American people to urban areas. Many people don’t realize that over 70% of American Indian people today live off the reservation.

Carlotta Cardana: Danielle and I have been friends since high school and we always wanted to collaborate on a project at some point. The idea for the project came from seeing the contrast between how Natives are portrayed in the media and what’s going on in those communities. There are certainly issues and problems, but there are also a lot of wonderful things happening, and it’s important to highlight those, too. I also realized that much of what I thought I knew about Native Americans came from misleading history classes and Hollywood movies, so it was also a learning opportunity for me.

Can you tell me a little bit of the backstory behind the Indian Relocation Act and the images that you took for this series?

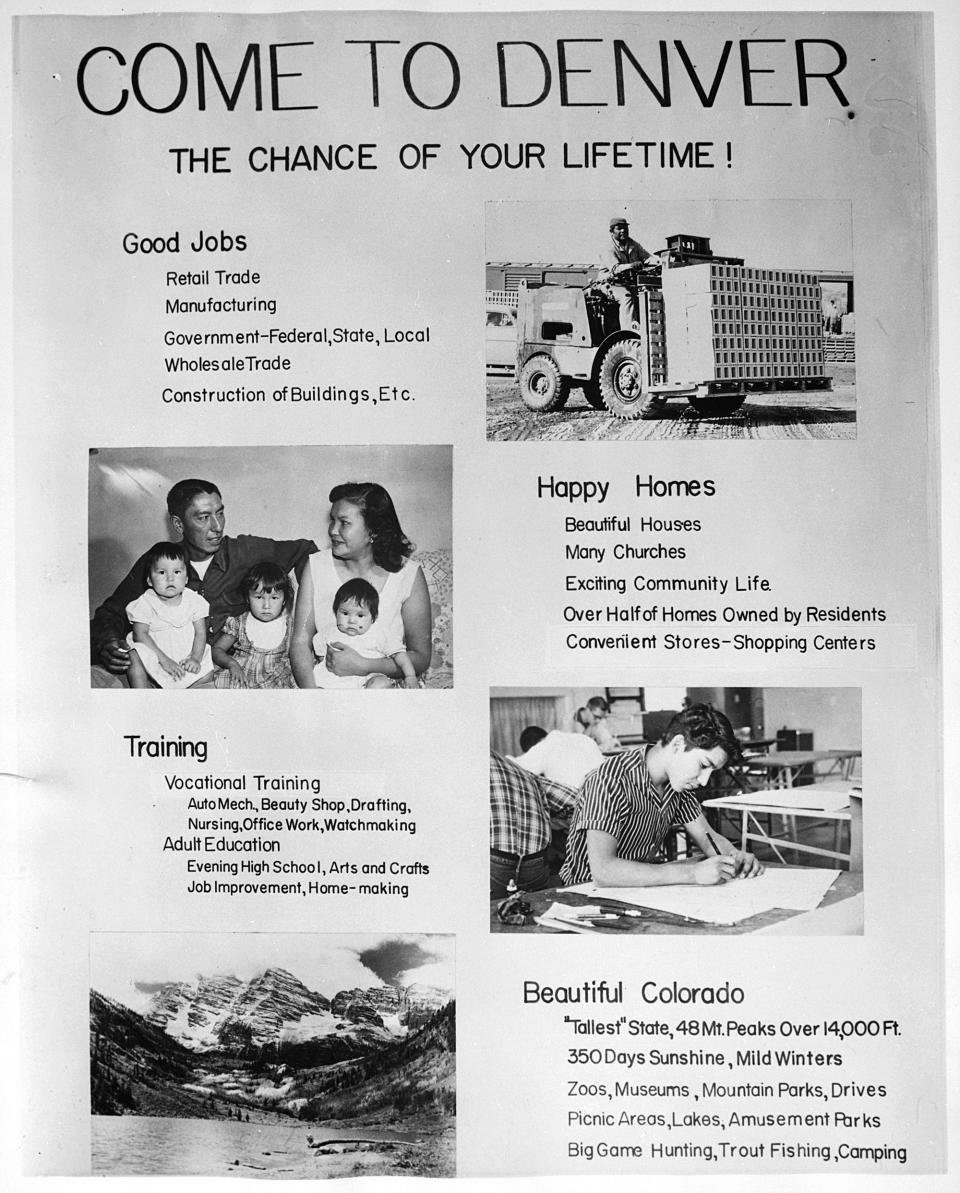

A “Come to Denver” relocation recruitment poster from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, circa 1950s

Danielle: The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 (also documented as Public Law 959) was a federal government law that was implemented to encourage Native Americans to leave Indian reservations, acquire vocational skills, and assimilate into the general population within urban areas like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Denver. The United States came up with this plan to solve what was sometimes referred to as the "Indian problem." The plan was to eliminate the reservations, which they were finding to be expensive, and the land was being realized as valuable.

Carlotta: As with the rest of the project, we decided to tell the story by focusing on the personal experiences of some people who lived it firsthand. We’ve interviewed and photographed everyone in a place that was important to them and relevant to their story, most often their home. We’re currently working on a short documentary film to go alongside the photographs, and we are also doing extensive research in archives to include historical images and documents in the final piece.

How did you choose the people you photographed?

Danielle: We wanted to focus on interviewing people in Denver, as it was once the headquarters of this relocation program. Since I live in Denver and am pretty well connected to the Native American community here, I was able to identify people to be part of the project that had direct connections to the relocation program.

Carlotta: We like to highlight people who are quite active within the communities and that are a source of inspiration. As well as Danielle’s connections, we partnered with local organizations to reach out to further people.

Buffalo Barbie (Diné, Navajo People) is two-spirit and an advocate for LGBTQ rights within the Native American community. She won the title of 2019 Miss Montana Two-Spirit and uses this as a platform to speak to other Native Americans about the blessings of being a two-spirited person.

What was your goal with these images, what story did you want to tell?

Carlotta: I really strive for my pictures to be accurate and truthful, I want the portraits to be about the person photographed as much as possible. As a portrait photographer, it’s natural to have ideas and plans ahead of the shoot but I prefer to have a more collaborative process with the sitter. American Indians have often been misrepresented in the media, or have had their photographs taken based on the photographer’s preconceived ideas. This has resulted in the strengthening of stereotypes and the idea that the Indigenous population is “part of the past.” My aim is to create images that belong to the 21st century, just like the people in them.

Danielle: Our ultimate goal is to tell stories of Indian Country by providing a platform for Native American people to tell their own stories using their own words and firsthand experiences. It’s also important for us to uncover buried histories that aren’t talked about or ever told in schools.

Native American children in the Uptown area of Chicago, 1977

Can you describe the juxtaposition of the current portraits you took versus older archival photos and how they relate or differ?

Carlotta: A lot of people still think of headdresses, teepees, and horses when you mention Native Americans, or that they only live on reservations like in “the old days.” This hasn’t been the case for over a century, and the archival images help show that. Both the archival images and my current portraits show Natives fully belonging to the era they live in, which is not that obvious to many people. We also use historical images to help tell the story of what happened after colonization — for example, during the boarding school era. There are some before/after portraits of children in the schools that are heartbreaking. It’s important to see those images because most people don’t even know that kids were taken from their family at a very young age and stripped of everything they had and knew. Finally, at times it’s really nice to see how traditions have continued and evolved by having the old and the contemporary side by side.

How long did the project take?

Danielle: The Red Road Project is still an ongoing project that began in 2013. The current topic that we are covering is also still a work in progress. We began to research and work on this subject in early 2022. We plan to have this chapter completed by mid-2023, with an exhibition to showcase the work and stories.

What did you learn from doing this project?

Danielle: I’m still learning and will forever be a lifelong learner. Each time we sit down with someone and interview them, I always take something away from that experience. It’s not very often that American Indian people have been given the opportunities to tell their own stories and experiences. In many cases, when we talk to people, it may be the first time they are reflecting on their life and telling their story out loud to someone. The historical trauma that our people have been through is extremely painful, and it’s been transferred from generation to generation, but the resilience and the healing is what is so powerful. In a way, listening to others tell their stories out loud is healing for me and for what my own family has been through.

Carlotta: Doing this project has been like getting an education all over again, both in terms of history and also on a much more personal level. History books can be very subjective to the country and the culture they belong to. It’s a story told by those who won wars and got into power. We learn that Native Americans suffered physical and cultural genocide, but we are not really told the extent of it and, mostly, how the oppression still continues today. Listening to all the stories we collected during these years has also been a very humbling experience for me. I became well aware of my privilege as a white woman growing up in a loving family in a small town in northern Italy. I am in awe at the strength and courage of everyone we met along the way.

An article on Native American relocation published in Florida's Sarasota Herald-Tribune on March 15, 1953

What do you hope people take away from this?

Danielle: Any time someone can take away something they didn’t know before, even if it’s just a small fragment of information, I consider that a win. I always hope that people will leave with lingering thoughts and a curiosity to know more. Being informed and then talking about it with others is crucial when it comes to American Indian histories. If you learn something new but don’t talk about it, that is a form of erasure, and through this project and our work, I’m hoping to redirect that.

Carlotta: As Danielle mentioned, I’m hoping people will learn something they didn’t know or that things aren’t as they thought they were. I also hope it might encourage people to challenge their beliefs in general. To be curious and open, rather than afraid or guarded, to whom and what life brings them.

Crisosto (Mescalero Apache) is a published poet who writes pieces that support the LGBTQ initiatives he is involved with as a two-spirit, Indigenous man. Growing up on a reservation, he was exposed to a different point of view in terms of what it meant to be gay. Among his people and in various Indigenous teachings, same-sex attraction is described as being "two-spirited," which is rooted in traditional philosophies of gender-defined spaces: a male and female universe, a male and female rain, Father Sky and Mother Earth, etc. It is believed that among these spaces, some people are born with the gift of walking between identities and offering value from both worlds. Having a two-spirited person in your family has historically been considered a blessing because many two-spirited people went on to become sacred people within the community. In his language, the closest word for "gay" is "nde'isdzan," which literally translates to "man-woman."

Sarah (Shoshone, Arapaho) is from the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. She has made Denver her home and could be considered an "urban Indian." Denver was once part of the original homelands of her people before they were forcibly relocated to Wyoming. Sarah is an advocate for health and fitness for Native American people, as obesity and diabetes are often major health concerns. She often travels back to her reservation, where she takes youth into the Wind River Mountains in order to reconnect with the wilderness and learn healthy lifestyle habits.

Rick (Kiowa, Cherokee) is originally from Oklahoma but has made Denver his home since 1984. Rick has proudly dedicated his life to serving Indian Country in various capacities, both personally and professionally, and now serves as the executive director at the Denver Indian Center. After the Indian Relocation Program struck the Denver metro area, the Denver Indian Center was born out of a need to have a centralized place in the city for Native people to congregate, host gatherings, celebrate culture, and provide resources for American Indian people who were navigating city life for the first time. Today, the Denver Indian Center still serves Native American people with various programming, including the Honoring Fatherhood Program, food pantry, Elders Circles, various cultural and language classes, and ceremony events.

Walt (Oglala Lakota) is the founder of the Stronghold Society, a nonprofit organization dedicated to building skate parks throughout Indian Country. In 2011, he built the first skatepark on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. "Skateboarding saves lives, when you put Sitting Bull or Black Elk on a skate deck, they are literally skating their culture, and there is a sense of pride that comes with that," Walt said. Suicide on the reservation is the second-leading cause of death and a crisis for youth. "The work I do through Stronghold Society is dedicated to instilling hope and supporting youth movements. We don't do suicide preventions — we do 'live life' call-to-action campaigns."

Paul (Oglala Lakota) is from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He served a short time in the military after graduating high school and returned to the reservation. He was having difficulty finding a job and soon heard about the Indian Relocation Program and decided to apply. He was accepted and first sent to Los Angeles to go through an appliance training program and then to Chicago, where he worked in an assembly line for a TV manufacturer. "When I got off the bus, they put me in a boarding house. There were a lot of Indian guys in there, mostly from the Southwest tribes and here for the relocation program, too." In 1970, he decided to settle in Denver with his wife and has been there ever since. "There’s a lot of people in Denver and I like that," Paul said. "Back home on the reservation, there isn’t much." Paul is unique in that his experience in both boarding school and the relocation program embody what the government was trying to achieve. He became a devout Catholic and felt the relocation program was a good experience.

Carla (Oglala Lakota) is from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. After graduating high school, Carla left the reservation for the first time and moved to Denver in hopes of opportunity. "I didn’t know how to live in a city," Carla said. "I experienced extreme culture shock, but I kept remembering what my family told me when I moved and that was to always remember who I am and where I come from." At one point, Carla felt so overwhelmed that she succumbed to alcohol addiction. After struggling for years, she had an awakening moment that caused her to sober up and remain sober to this day. "I took a step back and realized that I’m the matriarch of my family. My mom was gone, and all my family was back home on the reservation. There was no one else for my kids to look up to but me, and that got me focused on sobriety." Throughout her career, she has focused on helping the unhoused Native population in Denver and those with addictions.

Patrick (Lakota) is from the Standing Rock Nation and serves as an outreach coordinator for the Denver Indian Family Resource Center. Patrick left the reservation when he was 9 years old and went to boarding school in South Dakota. After graduating, he didn’t want to go back to the reservation, so he joined the Job Corps and eventually the military in 1968, and he served in Vietnam. "Going over there and seeing how people lived in a different country really brought me to my senses. I just couldn't understand why I had to go across the ocean to see people that were Native like us and how they were getting exterminated," he said. "What I have seen over there was exactly what was happening here in the US to us Native people." After his tour in Vietnam, he came to Denver, where his family had relocated, but experienced PTSD. He couldn't manage life in the city, so his family took him back to the reservation in North Dakota to go through healing ceremonies. Eventually, Patrick came back to Denver. An elder himself, he dedicates his life to helping Native elders through his work at the Denver Indian Family Resource Center. "I just can’t sit still and watch people suffer because I, myself, suffered. So, in return, I give back."

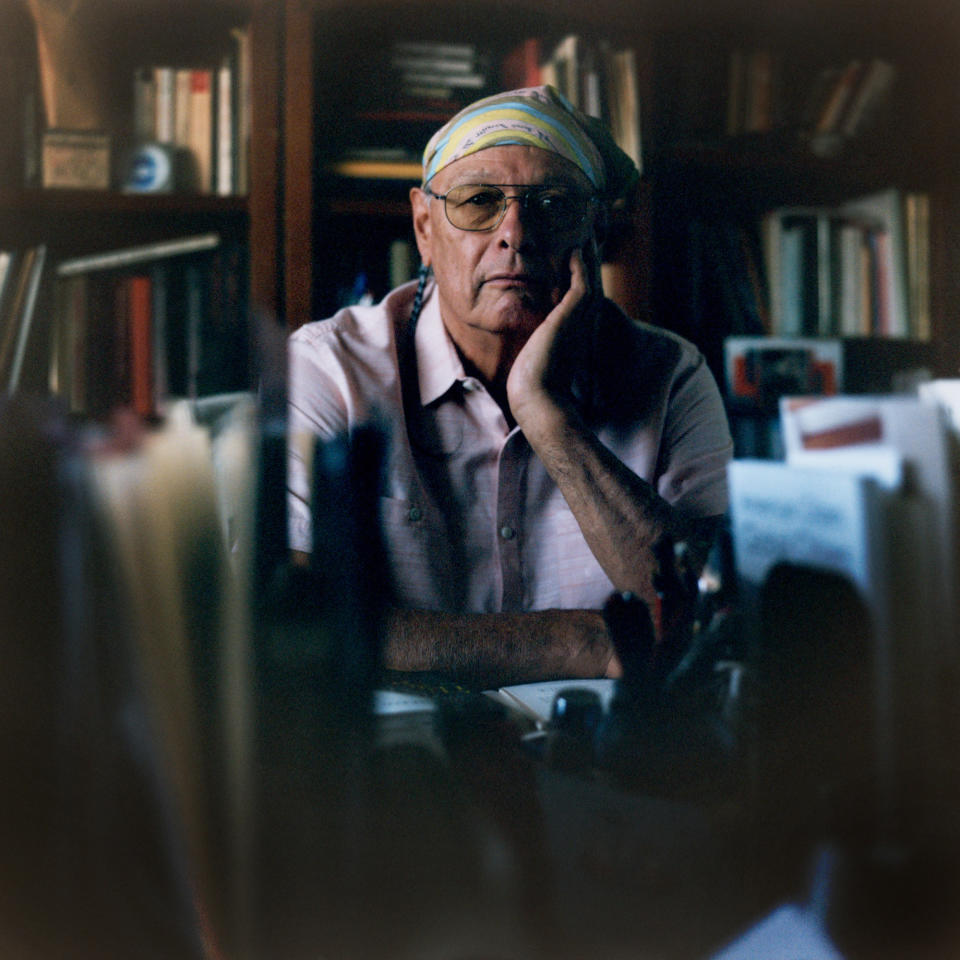

Rick (Oglala Lakota, Northern Cheyenne) is a highly respected elder in the Denver community, which he moved to in the late 1960s. He was the first Native American to graduate from the University of Nebraska, studied law at the Native American Rights Fund in Boulder, and worked on many landmark cases concerning the civil rights of American Indian people in prison. He was the first to establish a sweat lodge in a correctional facility. Rick later focused much of his career on American Indian education and, since retiring, continues as a researcher. In 2021, Rick discovered through research that an 1864 state law was still in existence that made it legal to kill Native Americans and take their property. He worked to get that proclamation voided by Gov. Jared Polis. Rick continues his work today through his organization, called People of the Sacred Land, which is dedicated to creating an equitable future for Indigenous people.

Bessie (Diné) was born and raised on Navajo Nation. Her parents only spoke Diné (Navajo), and she grew up in a very traditional way. Their transportation was a horse-drawn wagon, and they lived with no running water. By age 12, she was herding, shearing, and butchering sheep, weaving traditional rugs, and she had learned to cook. In her teen years, she was taken to boarding school. "It was not a good experience. I had a rough time, and they gave me a Western name," Bessie said. "The only language I knew, Navajo, was forbidden. My self-identity was totally different than the Western way of life. I wasn’t allowed to use my birth name for many, many years and I was told I was living the wrong way — that I wasn’t living a Christian life and therefore I was bound for hell." In 1956, Bessie moved to Denver, started a family with her husband, and was fortunate to get a job as a file clerk at the local hospital. After her retirement in the 1990s, Bessie began to reflect on her life and to reclaim her Diné identity. "There was a point where I was ashamed to speak Navajo, even to my parents." Today, she is outwardly proud to be a Diné woman. She makes a point to pass down her cultural knowledge to her children and grandchildren and spends her retirement years making jewelry with her daughter.

Darius (Diné, Black) currently serves as the director of the Anti-Discrimination Office for the City of Denver. As a civil rights advocate, his wealth of knowledge and ability to navigate the governmental systems has made him an asset to the community, especially Native Americans residing in an urban area. He was born and raised in Denver and is considered an "urban Indian" but was able to spend much time on the Navajo reservation with his grandmother while growing up, which kept him closely connected to his culture. The number of American Indians living in urban settings accelerated in the 1950s and 1960s because of the Indian termination policies of the era, when the US government encouraged Native people to leave their reservations and assimilate into mainstream culture. Today, more than 70% of Native American people reside in urban areas.