Uncovering the stories behind unmarked graves in Shelby

Leola Rankins. Matilda McCombs. Michael Wills/Wells. William Thomas.

For many years, the four names were lost to obscurity, mostly forgotten and relegated to an empty space covered in grass and lined by trees in Shelby’s most historic cemetery.

The four, whose deaths spanned as far back as 1874, were just a few of many unmarked graves discovered in a previously segregated section of Sunset Cemetery. At least two of them were former slaves.

The path to discovering their names and shining a light on their lives traces back to 2020 after a simple stroll among the graves led to a question and the pursuit to find answers.

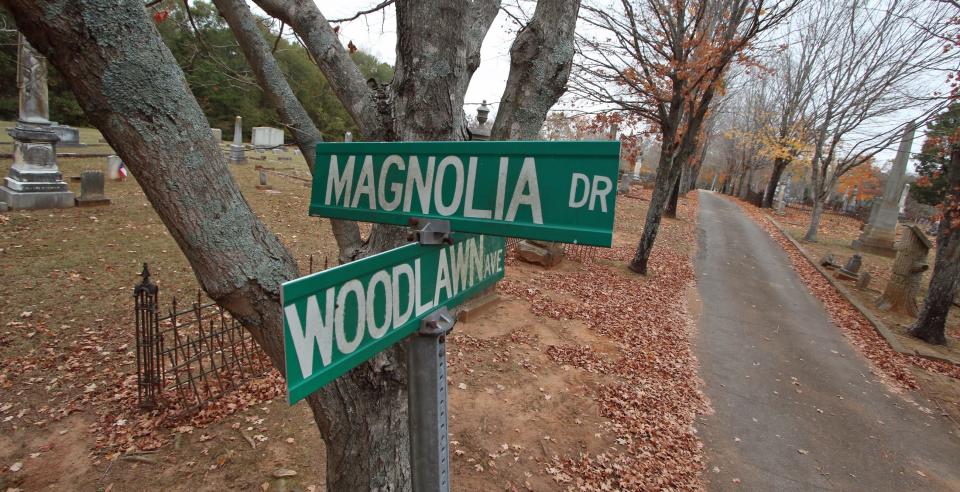

Sunset, a beautiful cemetery located on rolling acres of land with tree lined paths off of Sumter Street, was established in 1841, and the section of unmarked graves at the western edge dates back to at least 1876.

In May of 2020, Zach Dressel, curator for the Earl Scruggs Center, had just moved to town and was taking a Sunset Cemetery tour with Joe DePriest, retired reporter for The Observer and co-author of a book centered around the people buried in the historic graveyard.

When they came to the older section, on the western side of Sunset, Dressel asked why there was such a large empty field among all the gravestones.

“He said, ‘There’s this legend that that is where a lot of African Americans were buried,’” Dressel said.

It piqued Dressel’s interest and, as it was during COVID, he had plenty of time on his hands so he began digging into archives and historical documents, eventually coming across a map by Paul Kyzer from 1886.

“He showed a segregated cemetery and a church,” Dressel said.

The discovery was exciting as it indicated the local lore was true.

“There’s actually something to this,” Dressel said. “So I started to dig in.”

He said he has a theory that the church, which became the first Black school in Shelby, was the original Shiloh Baptist Church. He said Michael Wells was one of the founding members of Shiloh Baptist and a Michael Wills or Wells was one of the four documented names in the segregated section of the graveyard.

Dressel eventually found a WPA, or Works Progress Administration, survey from the 1930s, and it too showed the segregated Sunset Cemetery and documented that the African American section was overgrown and unkempt with knee-high trees and bushes with only the four markers remaining. The names were documented, preserving those four people even as the segregated section of the cemetery faded into obscurity over the years.

Once Dressel had those four names in hand, he approached the city.

“I said I found evidence that this exists, and something should be done about it,” he said.

City Council was supportive and recommended putting together a committee to determine what the next steps would be. Dressel got in touch with Chavis Gash, one of the leaders in the Black community, and they put together a committee of people.

Since then, Dressel said he’s done more research and discovered more information, including documentation that the segregated section wasn’t closed until the 1920s, and it had become a pauper’s cemetery where many children were buried. The mortality rate was high among children during the early 1900s, and many families couldn’t afford the expense of a funeral so they would be buried in unmarked graves.

Dressel said he went through death certificates from that time period and confirmed many children were buried in the pauper section. With the addition of two African American cemeteries - Eastside on Lineberger Street and Webb Memorial Lawns on Eaves Road, that section closed and Sunset eventually became open and desegregated.

In 2021, an anonymous donor paid for a ground penetrating radar study to be conducted, and it was completed that summer.

Dressel said the results weren’t what they were expecting.

The study found around 44 anomalies with 35 very likely to be graves. It also found a cistern or well that they theorize was attached to the church and what appeared to be the foundation of the church. Dressel said they weren’t expecting the graves to be so close to the treeline with only a handful located in the empty field and the majority concentrated along the woodline. Dressel said after going over these results, they thought it was possible they missed many of the graves, and there are more back in the trees. He said his theory is that the now towering woods were the knee-high trees mentioned in the WPA survey from 75 years earlier. The property now belongs to the Episcopal church next door, and Dressel said the church has been very supportive of efforts underway to preserve and honor the unmarked graves. A second GPR is currently in the works.

“It tells a remarkable story about early African American history in this county,” Dressel said. “It’s why we want to learn more and dig deeper, and we think the woods are going to give us some answers.”

Dressel said they are now garnering public input and support through public forums.

They want to seek input from the community on a future monument and educational markers.

Dressel said it was important to give a historically marginalized and underrepresented community members a voice.

“It’s certainly an untold story that needs more context,” he said.

The committee is also in the process of starting a nonprofit to assist with funding and putting a face to the initiative.

The ultimate goal of the project is to memorialize all who of the known and unknown people buried in the cemetery, clean up the forested area, list it on the National Register of Historic Places, create educational opportunities and build connections in the community.

The first public forum was held last week at Holly Oak Park and was attended by 22 people. Gash said he hopes to eventually create a social media presence and a website. They are also in the process of collecting stories, documents, memories and information from the community.

He said they hope to collect things connected to the segregated graveyard, such as old photos, information from family Bibles, death certificates, old news stories and handwritten notes or letters.

“We want to record history too,” he said to the people at Holly Oak Park. “You are a very important part of this project.”

Gash said there will be at least two additional public forums scheduled for the east side of Shelby and another in the Kingstown community. He said he doesn’t have dates nailed down yet, but it will most likely be the first of next year.

During the forum, he said there is no timeframe for erecting a monument and markers.

“We are taking it one frame at a time to get to that point,” Gash said. “Ultimately whatever we have out there, we want it to be endorsed by the community.”

He said they want to celebrate the lives of people who didn’t get that recognition when they were buried at Sunset.

“It’s important we have these sessions so people are aware of what’s going on and the things happening behind the scenes,” he said.

If people have additional questions or information they would like to share, they can email ourstoriescommittee@gmail.com or call Chavis Gash at 980-406-6838.

This article originally appeared on The Shelby Star: Uncovering the stories behind unmarked graves in Shelby