Under the baobab: Emmett Till should not — and cannot — ever be forgotten

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

My mom told me to put on my one suit. Why? It was the middle of the week.

“We’re going down to Rayner’s to view that boy’s body.”

I knew who she was talking about. I didn’t want to go.

“Ma, I didn’t know that Till boy.”

“You knew him. He used to hang out with those teenagers down at the pool. He stuttered just like you. So get dressed. We are going to pay our respects to his family.”

Emmett Till was 14, a few years older than me. We were both still in primary school. It was 1955, a year after the Brown v. Board decision, which outlawed racial segregation in public schools. But laws and Supreme Court decisions don’t change how people behave. Very little had changed in our white dominated, white supremacist country. Segregation and discrimination still ruled.

There were thousands and thousands of people lined up outside Rayner’s funeral home. It took us over two hours to get inside the building. It was a hot summer day in Chicago, but most people were dressed in their Sunday best, out of respect. The crowd was quiet except for the occasional screams and wails coming from inside the funeral home. When we got to the sarcophagus, I understood what the screaming was about. The horror I witnessed in that glass covered open casket has haunted my nightmares for 70 years. With his mother’s permission, Jet magazine published a picture of Emmett’s mutilated corpse. The whole country saw what I saw. The racists had not been content with just killing the 14-year-old. They tortured him, beating him mercilessly, breaking bones in his wrists, legs and face. Trying to justify the atrocity, one of them wrote,

“Well, what else could we do?... I stood there in that shed and listened to that n----- throw that poison at me, and I just made up my mind. ‘Chicago boy,’ I said, ‘I’m tired of ‘em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you, I’m going to make an example of you — just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.”

The “poison” was Emmett refusing to acquiesce. A couple of months later these cowardly child killers stood trial. Twelve of their peers, all white, all men, took 67 minutes to exonerate them. Some of the jurors later admitted that they knew Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam were guilty of Till’s murder. But they did not think imprisonment or the death penalty were appropriate punishments for white men who had killed a Black child.

Emmett’s lynching did not generate compliance but resistance. Mamie Till-Mobley toured the country telling the story of her son’s life and death. Rosa Parks cited the murder of Till as one of the reasons she refused to move to the back of the bus, which began the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. Parks said, “I thought of Emmett Till and I just couldn’t go back.” In 2007, Rep. John Lewis sponsored a bill called the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act. Whoopi Goldberg took 10 years of her life and resources to make feature film “Till” so everyone could know the truth. In 2021 President Joe Biden signed into law H.R.55 — Emmett Till Antilynching Act — which finally made lynching a federal hate crime.

This last week on the 82nd anniversary of Emmett Till’s birth, President Biden established The Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument. The new national monument includes sites in the Mississippi Delta and Chicago that were central to Emmett Till’s lynching, funeral, and the acquittal of his murderers. We cannot bury the past no matter how hateful. By remembering the atrocity of the lynching of a child we help ensure it won’t happen again.

Laws don’t change a society. We, the people, do.

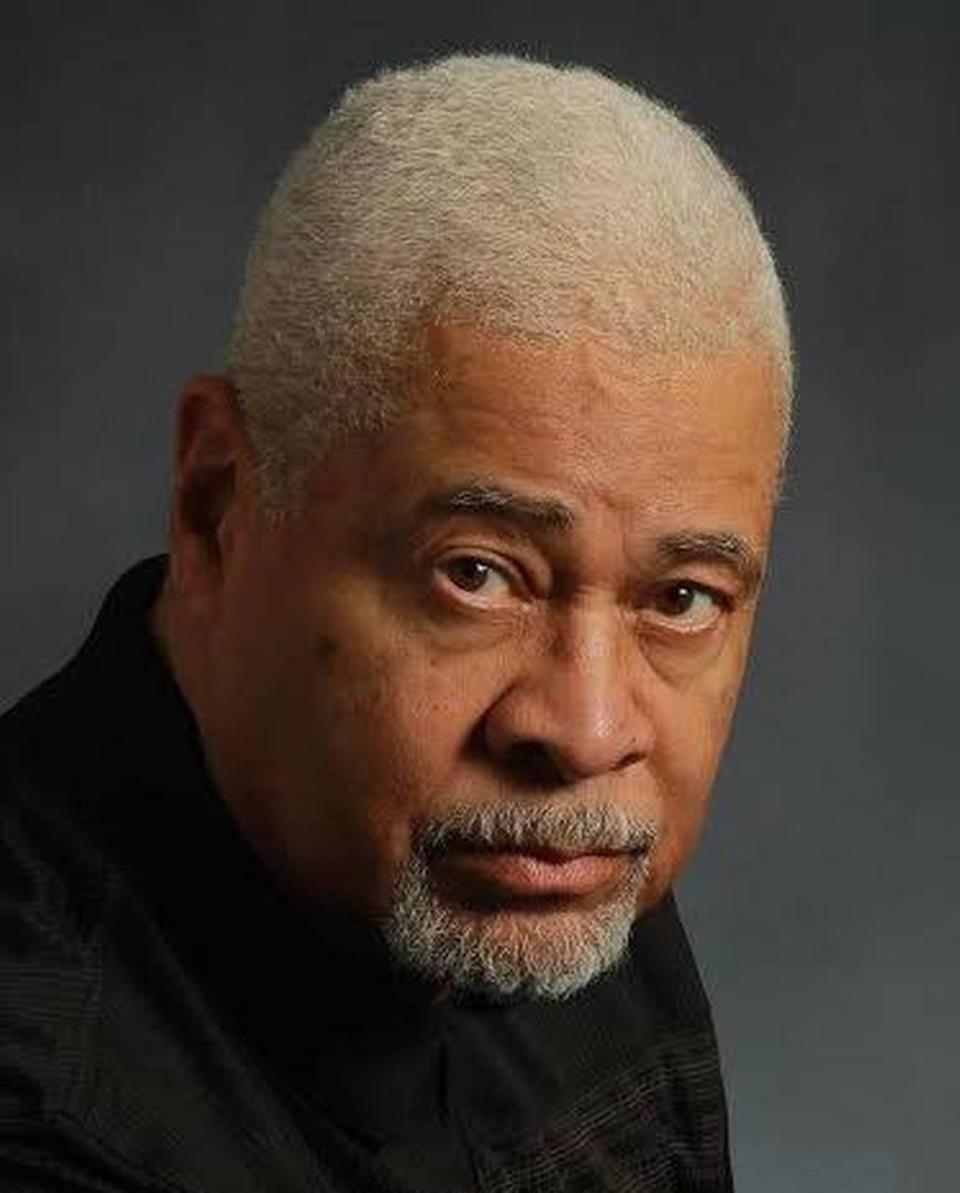

Charles Dumas is a lifetime political activist, a professor emeritus from Penn State, and was the Democratic Party’s nominee for U.S. Congress in 2012. He was the 2022 Lion’s Paw Awardee and Living Legend honoree of the National Black Theatre Festival. He lives with his partner and wife of 50 years in State College.