An underfrog story: MSU research shows 32 frog species thought extinct still live in wild

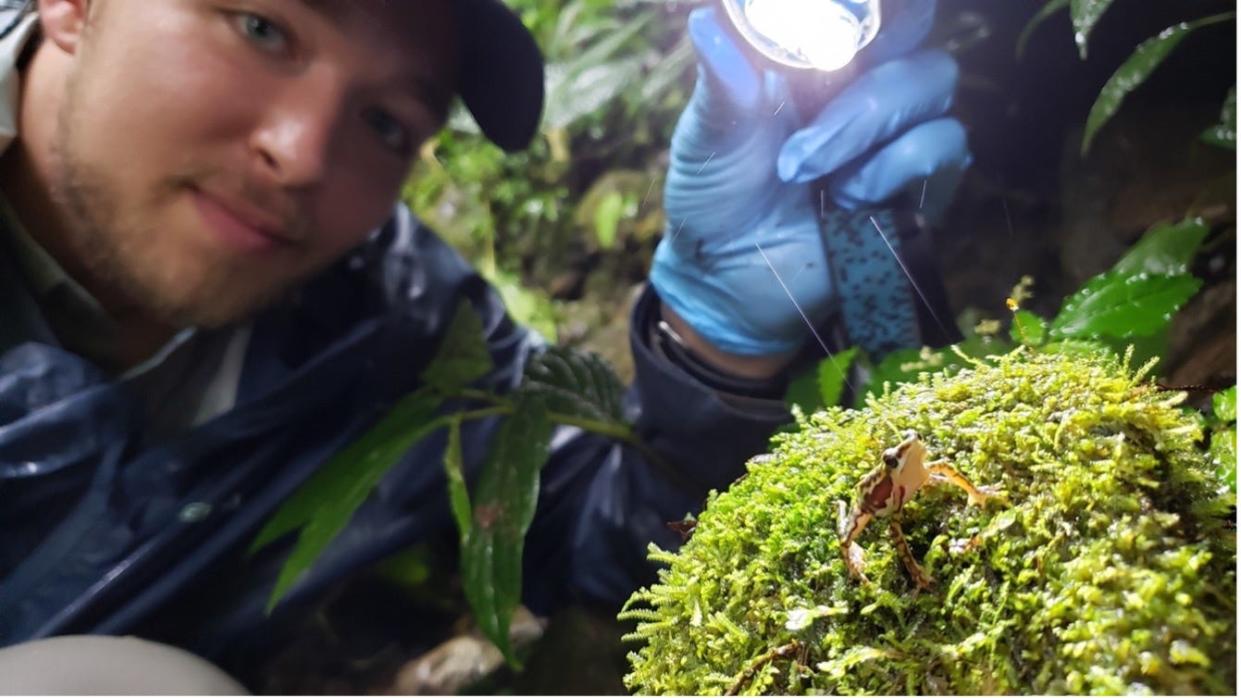

“I can’t tell you how special it is to hold something we never thought we’d see again,” Michigan State University doctoral student Kyle Jaynes said following a trip to South America to search for harlequin frogs.

Jaynes, a member of MSU's Department of Integrative Biology, and the ecology, evolution and behavior program, was part of a team that helped bring as many as 32 harlequin frog species, academically at least, back from the dead.

The team, through a combination of literature review and fieldwork, showed that some of the colorful, patterned and varied neotropic species, once widespread through the entire range of the Ecuadorian Andes but in recent decades thought to be extinct, are still surviving in the wild.

It’s an underfrog story, as Matt Davenport put it in an MSU Today article. The team's findings are presented in a new study published in the journal Biological Conservation.

Since the 1980s, a pathogenic fungus called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis has killed members of more than 500 species of amphibians, according to a recent estimate. It’s been characterized as an apocalypse by National Geographic.

The fungus has decimated populations around the world for about 40 years, pushing many species to extinction. The harlequin frog genus has been hit exceptionally hard and experts believed more than 80% of its species were driven to extinction, Davenport reports.

Around the turn of the 21st century however, people started spotting species that had been missing, some for decades. Reports became more frequent as time went on, but sightings were recorded as individual incidents.

In 2019, Jaynes won a one-year, $8,770 National Geographic Society grant that allowed him to bring disparate reports together to provide a more complete account on the frogs’ status, which he, Sarah Fitzpatrick, an assistant professor in the College of Natural Science based at the W.K. Kellogg Biological Station, and their colleagues in Ecuador have done.

The grant also enabled the MSU researchers to travel to five different sites in Ecuador in late 2019 and spring 2020 to look for rediscovered frogs across a range of habitats. Fitzpatrick described the first discovery of a harlequin frog in the field as “very dramatic.”

“We were all spanned out across this field, but nobody thought we were going to see this frog," she said. "Then one of our collaborators started shouting in Spanish, ‘I found one!’”

When researchers found a frog, the team would collect saliva samples for genetic studies.

“If you’ve ever done an ancestry test that uses your spit, that’s the idea,” Fitzpatrick said. “It’s like 23andMe for frogs.”

They also swabbed its skin to look at which microbes, including Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, were living on them.

Jaynes said experts didn’t think the frogs existed a decade ago. Now they have their DNA samples, providinginvaluable information.

Through examining the DNA, the team found species that had been missing and presumed extinct for longer had less genetic diversity than frogs that disappeared more recently. Low genetic diversity could indicate a species is more susceptible to future stressors like a new strain of the fungus, climate change or habitat loss, Davenport reported.

The information is needed for developing strategies to conserve and protect rediscovered species, but the researchers still need to gather a lot more information, Jaynes and Fitzpatrick said.

This research provides some hope for the amphibians. But researchers also hope it creates a sense of urgency around conserving the still critically endangered rediscovered species. Rediscovery does not equal recovery, Jaynes said.

“This story isn’t over for these frogs, and we’re not where we want to be in terms of conservation and protection," he said. "We still have a lot to learn and a lot to do.”

Contact Bryce Airgood at 517-267-0448 or bairgood@lsj.com. Follow her on Twitter @bairgood123.

This article originally appeared on Lansing State Journal: Michigan State research shows 32 frog species still exist, aren't extinct