Understanding deer behaviors could help help prevent collisions with cars in Wisconsin

Preventing roadkill often focuses on a few main strategies: Drive carefully. Slow down. Be extra vigilant during the November breeding season.

Although often left out of the conversation, scientists say understanding more about deer as a species could also help reduce the over 16,000 collisions that reportedly happen between deer and Wisconsin drivers each year. For example, drivers should know that deer are naturally drawn to roadsides at night because of their specific preferences for food and land cover.

In other words: “They’re really hard to avoid if you don't have any sense of their behavior,” said Chris Young, who studies conservation and biology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “You hear people say all the time, ‘Those dumb deer, they just walked into the middle of the road.’”

Wisconsin’s population of more than 1.66 million deer is growing, meaning a reduction in the overall herd would also reduce roadkill. Hunting is the main strategy used to reduce the deer population, but the number of bow and firearm hunters statewide is declining. The number of those hunters dropped by 111,581 between 2000 and 2022, the most recent data available. In 2022, hunters killed 340,282 deer.

More: Fewer deer hunters means less donated venison is making it to Wisconsin food pantries

For most people, there’s a social, mental and emotional toll that comes with hitting an animal with a car — especially if the deer doesn’t die immediately, said David Drake, an urban wildlife expert and professor at the UW-Madison. Last year, five Wisconsin drivers died and 537 were injured due to deer-related crashes, according to the state Department of Transportation.

But few people fully absorb the cost of those collisions because of insurance coverage, meaning there’s not much incentive to change the status quo, Drake said.

Car-deer collisions are costly

Between fiscal years 2001-02 and 2022-23, Wisconsin devoted $16 million in public funds to manage deer killed by cars, according to the Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

Today, the DOT pays contractors to manage the carcasses on interstates, U.S. and state highways, while counties manage other local roads. Dane County paid $78,320 to one private contractor in 2022 to manage deer carcasses.

In the last five years, Sheboygan-based Acuity Insurance has paid over $40 million on more than 7,500 claims related to animal collisions in Wisconsin. The average car repair for an animal hit costs $5,355, not including the customer’s deductible, according to the company.

Those figures exclude the social and financial costs on healthcare systems. Roadkill also places a physical and environmental burden on waste management facilities to take in hundreds of carcasses annually, some which could spread chronic wasting disease.

“This issue, it’s economical, it’s social, it’s animal welfare, it’s emotional,” Drake said. “There’s all sorts of different perspectives on this, and that’s what makes it so difficult.”

Deer are naturally drawn to 'edges' between landscapes, and roads carve out those edges

Deer are what ecologists call an “edge species,” meaning they prefer to live in areas with several types of land. Edges between forests, farms, wetlands, urban areas and other habitats provide a variety of places to find food, rest and hide from predators.

“And guess what Wisconsin is like?” said Scott Hygnstrom, deer ecology researcher and professor at UW-Stevens Point, who has been in 11 deer vehicle collisions. “With our agricultural settings, our forests and our wetlands, it’s pretty diverse. And that’s one of the reasons why we have lots of deer here.”

This creates a conundrum: Roads create those kinds of edges that deer are attracted to.

The middle of a forest has far less food for deer than an “edge.” It's on borders between landscapes where their favorite foods grow: berries; grasses; “browse,” or the tips of woody shrubs and trees; wildflowers or “forbs,” such as goldenrod, fireweed and lupine.

That’s why experts say it’s important to pay attention to the landscape when driving.

Some highway departments intentionally manage plants growing along roadways as a roadkill prevention strategy. For example, Washington and Green counties mow grass and vegetation along roadsides so animals are more visible to oncoming cars.

Deer are especially drawn to roadsides for food during the “spring green-up,” Hygnstrom said. It’s the season when shady, cool woods are still snowy, but roadside ditches warm up. Plants that grow along sunny roadsides are extra appealing to deer after enduring the long, hungry winter.

Car and deer collisions spike in the fall during the “rut,” or the late October through mid-November mating season. They spike again during the spring when fawns are born and 1-year-old, inexperienced deer go off on their own for the first time.

More: Collisions with deer spike every November. One surprising factor? Daylight saving time

Deer see best at night, but lack ability to perceive how fast cars are moving

Deer are “crepuscular” prey animals with eyes that work best in dim light. It’s why drivers are most likely to encounter them on roadsides at dawn and dusk. The majority of Wisconsin deer-related car crashes in 2022 took place between 5 and 6 a.m. and between 5 and 9 p.m.

During the day, deer bed down in sheltered, woody areas to rest and digest. Eating quickly, then retreating to safety for digestion is a predator escape mechanism.

Jennifer Smith is a behavioral ecologist at UW-Eau Claire. She said it’s useful to understand the deer’s “umwelt,” the unique ways an organism perceives the world.

For example, Smith said, loud noises could be used to scare the naturally skittish deer away from high-traffic areas or warn them as a car approaches.

When a car does approach, they are not conditioned or adapted to look both ways before crossing the road. Young, from Milwaukee, said deer are unable to discern the sound of one approaching car from the general roar of the freeway.

Deer also lack the ability to perceive how quickly a car is moving, according to Hygnstrom.

While deer might see or hear a car coming, they might not register it as a risk, he added.

Does Wisconsin use wildlife crossings, bridges or fences?

Bridges over roads, or passageways under them, for deer and other wildlife have been used successfully in some areas. For example, an 8-foot-high, 4-mile-long fence and several wildlife underpasses along Interstate I-80 in eastern Nebraska reduced road kill rates by 85%.

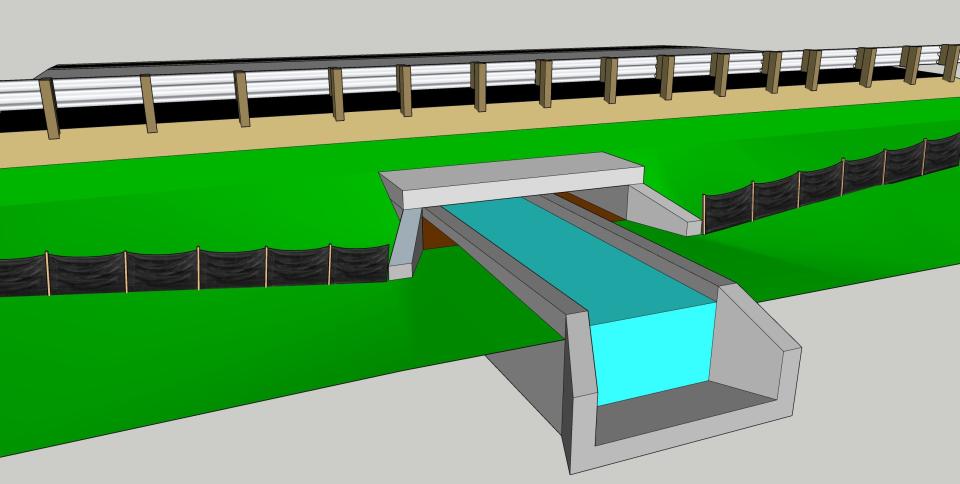

In Wisconsin, at least 60 "wildlife accommodations" have been installed over the past 20 years using state DOT funds, and eight more are currently under construction. Most of those projects are wildlife shelves under bridges and culverts.

The DOT “(does) not have any data to determine the success of these strategies,” according to an emailed statement to the Journal Sentinel.

“We have partnered with other organizations to do some limited studies in the past. For example, for one project in central Wisconsin, the researcher observed a 60% reduction in mortality of turtles following installation of fencing and a culvert eco-passage,” the statement added.

The DOT declined to disclose exact locations or photos, citing public safety, but provided a rendering.

Hygnstrom formerly taught at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and was among five authors of a 2013 research paper examining roadkill prevention efforts along I-80. He said it’s not a question of whether wildlife fencing and underpasses are effective, but how to get the public’s buy-in to pay for them.

It cost Nebraska $1.4 million to construct 4 miles of fencing. Hygnstrom said the project likely recouped the social costs of collisions, like hospital bills and car repairs, in a year.

The Nebraska project also targeted an area along the Platte River known for its large deer population and history of deer vehicle collisions. Hygnstrom said that in Wisconsin, determining where to put fencing along I-94 would be tough.

“Take your pick. That’s my point. Where in the world wouldn’t we need a fence to keep deer off roads in the state of Wisconsin?” he said.

Young said the issue of roadkill has been created over generations. That means it will take time to solve.

“At some point, we’re going to have to start changing the way we lay out roads. We’re going to have to start changing the way we transport ourselves across a landscape that has too many deer. Or we’re going to have to start changing the way that landscape appears to the deer.”

Cleo Krejci covers higher education, vocational training and retraining as a Report For America corps member based at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Contact her at CKrejci@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @_CleoKrejci.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Understanding deer behavior could keep Wisconsin divers safer