Understanding your property taxes: Ohio lawmakers propose changes as home values rise

Home values across Ohio have skyrocketed, and these historic increases will translate into significantly higher property tax bills for some homeowners but not others.

The math to calculate what a 30% or 40% increase in your home's value means for your property taxes isn't simple either. Ohio's constitution and state laws have created a complicated system of rules and exceptions for how levies can or cannot raise your taxes.

"We have 65 different taxing districts in Butler County," Auditor Nancy Nix said. "Every home is different, every township, every school district. There is no one size fits all, and that’s why it’s so hard to explain anything to anybody."

Some Republican lawmakers are hoping to change the calculations before property tax bills go out next year. The long-term goal is to make the calculations easier. The short-term plan is to reverse some of the tax increases about to go into effect.

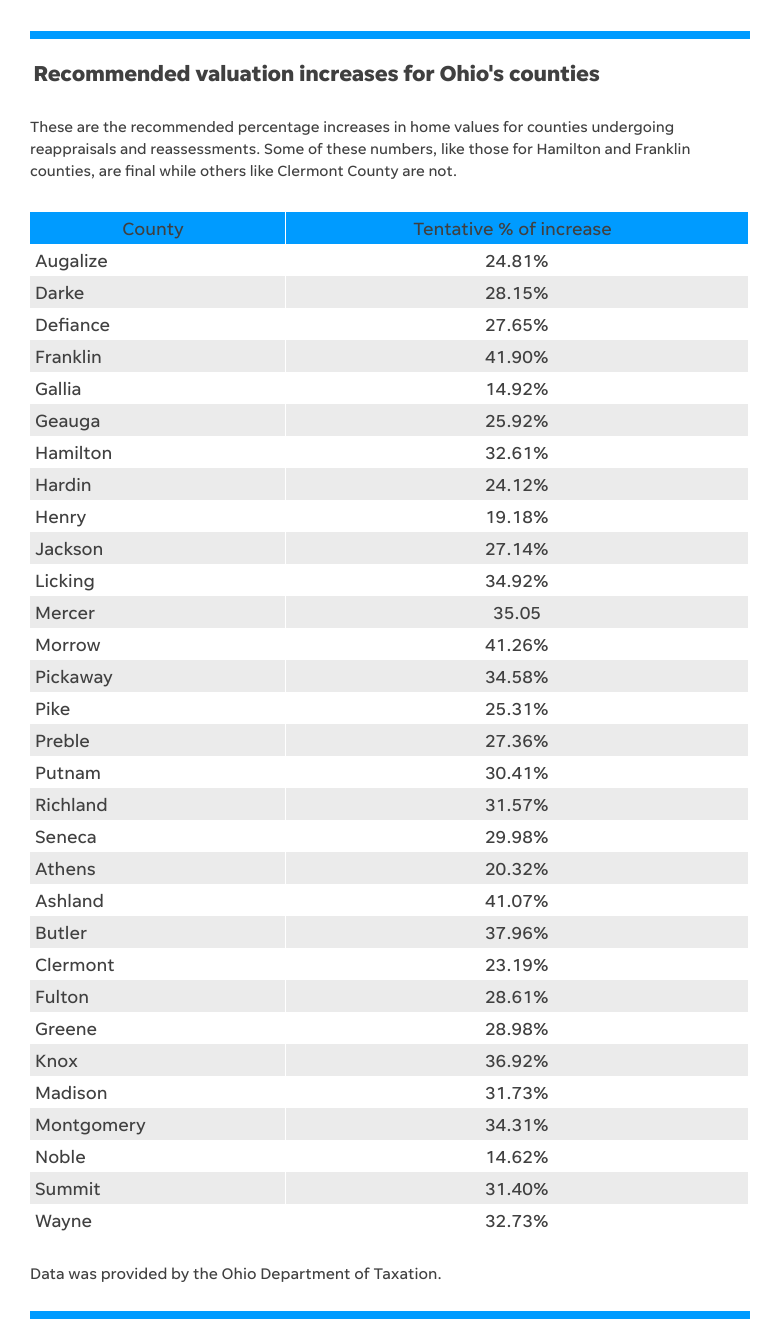

More: Franklin County home values jump average 41% in reappraisal - see how much your area rose

For example, the city of Middletown is a working-class community made famous by U.S. Sen. J.D. Vance's memoir Hillbilly Elegy. Home values there jumped above the countywide average to 40%, and its specific set of levies and exemptions could increase property taxes by more than 20%.

"One day we had two different women from Middletown crying, literally crying, on the phone," Nix said. "Nobody likes more taxes, but the well-off, they know they will be fine. It's the people on fixed incomes and the lower-income, they’re the people who are going to struggle."

Why some taxes rise with home values while others don't

Different levies for schools, libraries, and other local services are why homes with the same assessed value can pay very different tax bills. But equally as important to understanding Ohio's property tax increases is the kind of millage you pay.

Levies are calculated using a measurement called mills. They're one-thousandth of a dollar or $1 for every $1,000 of assessed value. When counties determine their tax bills, they take a home's taxable value (35% of what it's worth) and its total millage to calculate what property owners owe.

A home worth $400,000 would therefore have a taxable value of $140,000 and a single mill would generate $140 in property taxes. If that house was worth $500,000, a single mill would cost $175.

That's the basics of how property values increase property taxes, but Ohio's system isn't that simple. The state constitution divided millage into two categories: inside and outside.

The idea was local governments needed a certain amount to function, so your first 10 mills aren't voted upon and can't be taken away. It's the inside amount homeowners would always have to pay. Outside millage, on the other hand, is what voters approve through levies.

And inside millage behaves differently than outside millage.

Those first 10 mills homeowners pay rises with their taxable value. If a home's value goes up by 25%, as it did in the example above, then those 10 mills would rise by 25% as well. Outside millage doesn't operate like that.

Here's how it works: A school district passes a five-mill levy to collect $1 million a year. When property values rise by 25%, those five mills would generate $1.25 million. Ohio law prohibits local entities from collecting more than voters approve, so the mill rate gets artificially lowered. This is called effective millage.

In that example where a home's value rose to $500,000, the owner would see a $350 increase on their inside mills but potentially see their outside millage stay flat.

The caveat there is another quirk of Ohio law called the 20-mill floor.

This floor applies to school districts, and it says schools cannot drop below 20 mills even if that increases the total amount collected. Homeowners, like those in Middletown, who live in school districts at or around that floor will see school tax increases in percentages that closely match their value increases.

Keeping with the same example, a $500,000 home on that floor would pay $875 more assuming they had five inside mills for schools, five inside mills for other services and 15 protected by the floor.

On the flip side, homeowners living in school districts above the floor won't see the same increases. State law "lowers" those millage rates.

For example, Olentangy School District residents would only see a 4% increase in their taxes from a 35% jump in property values, according to Delaware County Auditor George Kaitsa. But three of his districts (Big Walnut, Buckeye Valley and Delaware City) are at that 20 mill floor and will see bigger increases.

Franklin County has two of its 24 school districts at the floor. And in total, the Department of Taxation says half of Ohio's school districts are at that minimum 20 mill level.

"These values, they’re not lying. The data is not lying," Nix said. "It's the Ohio Revised Code that has us in a bind, and only our lawmakers can fix it."

Different lawmakers, different solutions

In May, a group of southwest Ohio Republicans tried to change how home values get calculated, requiring the Ohio Department of Taxation to use three years of sales data instead of one.

They called it a "common sense solution" that would have dropped Butler County's increase from 38% to 24%. But the idea failed to make it into the state budget before lawmakers left Columbus for the summer.

"We had the fix in the Senate version of the budget, and the House pulled it out," Sen. George Lang, R-West Chester, said.

His goal, when lawmakers return in September, is to pass something, possibly a temporary switch to that three-year calculation, and make it effective before property tax bills go out next year.

"It's going to be disastrous if we don't fix it," Lang said.

More: Ohio expands its property tax exemptions, here's what you need to know

But Rep. Dani Isaacsohn, D-Cincinnati, isn't convinced that Ohioans need blanket relief from their property taxes.

"To me, property tax relief for people who need it the most makes sense," he said. "Property tax relief for those who can afford the increase in taxes just doesn’t seem like a sensical policy."

That's why he's working with Rep. Thomas Hall, R-Madison Twp., on expanding Ohio's homestead exemptions which lower property taxes for certain groups of people like seniors and disabled veterans.

Two other ideas being floated by both Nix and Hall are to reduce that 20-mill floor for public schools or restore some of the Local Government Fund.

"I know (lawmakers) are resistant to take back some of the tax burden," Nix said. "But if they really want to help, that’s a way to help."

Anna Staver is a reporter for the USA TODAY Network Ohio Bureau, which serves the Columbus Dispatch, Cincinnati Enquirer, Akron Beacon Journal and 18 other affiliated news organizations across Ohio.

Get more political analysis by listening to the Ohio Politics Explained podcast

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Ohio lawmakers propose tax changes as homeowners brace for big bills