The New Union Label: Female, Progressive and Very Anti-Trump

On a clear evening in Washington this past summer, Sara Nelson was in her element, waiting to speak to a revved-up crowd of union members at Reagan National Airport. Dressed in a navy flight attendants’ uniform, she stood out against the sea of jewel-toned business suits and union T-shirts.

If it intimidated Nelson that she was slotted to speak alongside two of the nation’s most notable progressives — Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — it didn’t show. Over the course of her seven-minute speech, Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants, excoriated American Airlines executives for outsourcing catering jobs and driving down wages.

“We’re here to call bullshit on that scam!” Nelson roared into the microphone. “American Airlines is responsible — is responsible — for the poverty wages in these kitchens!”

By the end, the crowd of several hundred was cheering louder for Nelson than it had for Sanders. As she stepped away from the podium, Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), who was up later, leaned over and playfully whispered in her ear: “I fucking hate you.”

Coming from Brown, one of the labor movement’s most beloved politicians, the salty jab speaks to Nelson’s emerging public profile. Though she leads a union with nearly 50,000 members from 20 airlines (the other major flight attendants union has a membership of 28,000) few people outside corporate boardrooms and airplane galleys know Nelson’s name. In the male-dominated universe of the American labor movement, however, Nelson is gaining altitude with a pace that resembles the dramatic emergence of youthful female politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“She has come from — I don’t want to say nowhere — she has come from not being very well known to being a star in the labor movement,” Brown said in an interview later. “She’s just so good. She captures the crowd and you don’t want to speak after somebody like that.”

Nelson’s rise can be attributed to a potent mix of progressive politics and relentless self-promotion. More than anyone else in the labor movement, she has tapped into the energy on the new left and used the media to her advantage, ascending past a ruling class of older white men to become one of the most visible labor leaders in America. She has crisscrossed the country lamenting the evils of unchecked capitalism and taken on the president with the gusto of someone running to unseat him.

Nelson’s first major burst of publicity came earlier this year during the government shutdown when she called for a general strike, a seldom-used nuclear option in which union leaders incite widespread work stoppages across multiple industries. A general strike hasn’t occurred in earnest since 1946, when more than 100,000 workers in Oakland, California, shut down the city for three days. While Nelson’s proposition was legally dubious—federal workers face severe consequences for striking without authorization—less than a week later, air traffic controllers called in sick, snarling flights up and down the East Coast. President Donald Trump caved hours later, and the longest shutdown in American history ended.

It's an accomplishment that Nelson proclaims in almost every speech. The fact that Nelson didn’t actually do anything tangible to end the shutdown—she was not in the room negotiating with Trump and has no direct influence over the air traffic controllers, who have a union of their own—is almost beside the point. What matters, in the eyes of more than a dozen people in the labor movement who spoke to me for this article, is that she said what an increasingly agitated swath of union supporters wanted to hear.

“She’s the closest thing to kind of a charismatic labor leader we’ve had since, you know, maybe Cesar Chavez,” said Peter Dreier, a union historian at Occidental College.

Nelson, 46, is now weighing a run to become first woman to lead the AFL-CIO, effectively the leader of organized labor in the United States, representing 12.5 million workers who still have the power to shape major legislation and swing elections. The election to replace the federation’s leader, Richard Trumka, who is expected to step aside, won’t happen until October 2021, well after a presidential contest that is shaping up as referendum on the nation’s tolerance for seismic left-wing change to the economy. Nelson has tied her candidacy to the same progressive ideas that are dominating the debate among the Democratic aspirants for the White House and wants to remake the labor federation as dramatically as candidates like Sanders and Warren hope to do from the White House. She rejects the current labor leadership’s moderate approach and unapologetically calls on labor to embrace a more liberal set of values as a way to reverse decades of systemic decline in membership and influence.

The labor movement is split—thanks to Trump, whose candidacy in 2016 created a schism in the labor vote that deeply embarrassed Trumka and probably helped deliver the White House to a president who openly despises unions. Nelson, however, is not interested in pulling the factions back together. She wants to repudiate Trump—and, implicitly, rank-and-file members of AFL-CIO unions who support him for his trade policies and broader war on establishment elites.

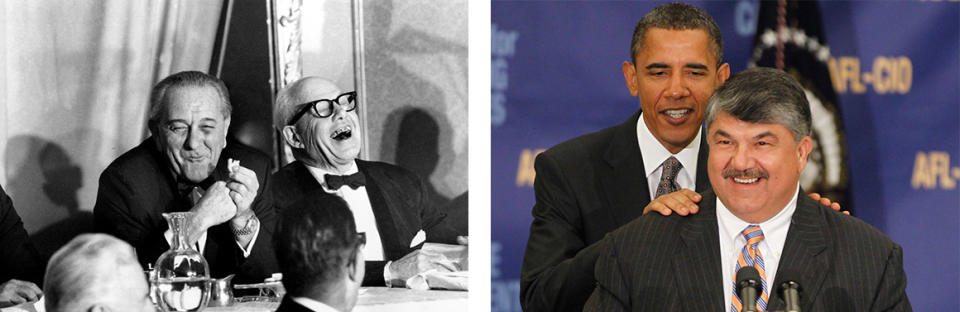

Nelson does not fit the classic profile of an American labor leader, at least not the cigar-chomping, pugnacious image enshrined in the public consciousness by the likes of George Meany and Jimmy Hoffa. Nelson, with her signature platinum blond hair, favors silk scarves, though she swears like a sailor. She grew up as a Christian Scientist, abstaining from medical treatment until her late 20s, but now advocates universal health care. Nelson is known for popping up on TV at all hours talking about workers issues, even those that don’t directly relate to flight attendants and has hired an outside media consultant to boost her public profile. It’s all a sharp contrast with Trumka, who lives for deer hunting every fall at his Pennsylvania property and began his labor activism representing mine workers. Nelson began at 30,000 feet and would rather spend time with her young son, Jack.

Her likely candidacy also embodies the growing influence of women in the labor movement and the shift of unions away from the blue-collar manufacturing sector to more white-collar jobs in service industry and government. While union membership rates among men have fallen by more than half since the early 1980s, the percentage of women has dropped by just 4 percentage points over the same period; as of last year, the rates were nearly equal. And in public-sector unions—a sector that gained 132,000 members from 2018 to 2019 despite a Supreme Court ruling outlawing mandatory collective bargaining fees—women now outnumber men.

“Sara Nelson embodies the changing demography of the labor movement, which is now increasingly women and increasingly people of color,” said Nelson Lichtenstein, director of the Work, Labor, and Democracy center at the University of California Santa Barbara.

She matches the demographic shifts but she is by no means a lock to replace Trumka. She has acquired detractors throughout her career, many of whom were reluctant to criticize her on the record for fear of reprisal. They see her as less of a coalition builder than a flashy, self-involved promoter. Perhaps most significantly, she would have to outmaneuver Liz Shuler, the AFL-CIO’s well-liked secretary treasurer, who has also expressed interest in running and would be a natural successor to Trumka. But Nelson’s candidacy alone could pull unions to the left on a host of issues, according to labor scholars and activists who have followed her career trajectory.

“If you want to lead the labor movement, you have to think bigger,” Nelson told me in an interview earlier this summer at an upscale restaurant in downtown Washington. Relentlessly on message, she hardly touched her salmon and kale salad as she deftly avoided sounding eager to replace an incumbent who hasn’t retired yet.

“Whether or not I hold a position that is a title position,” Nelson added, “I want to do everything I can to make this labor movement strong and work for working people and totally change the rules of the game in this country.”

Which raises the central question: Can labor return to its radically progressive roots, or will Nelson’s left-wing candidacy further divide a movement that was long a mainstay of Democratic support?

Nelson became a flight attendant almost by accident. After graduating from a tiny Christian Science college in St. Louis in 1995, she was working four jobs, barely making ends meet. A friend called from Miami Beach in 1996 and told her about her salary and benefits as a flight attendant. The next day, Nelson drove 300 miles to Chicago and interviewed with United Airlines.

The glamour faded when her first paycheck didn’t arrive on time. Desperate and out of money, Nelson rode a jump seat from Boston to Chicago just to eat free plane food. When she landed back east she went to the airline desk, and was told her check still hadn’t arrived.

As she began to cry, a stranger tapped her on the shoulder. It was a fellow flight attendant who wrote her a check for $800 on the spot.

“She [said], number one, you’ve got to take care of yourself, and number two, call our union,” Nelson said. “I learned everything I needed to about our union and the labor movement in general.”

From her earliest days, Nelson saw the dark side of a profession that depended on women and devalued them in equal measure. Up until 1970, United flight attendants could not be married under company rules, and it was common for airlines to show flight attendants the door at 32. By the mid-1990s, when Nelson began flying, attendants had just finished waging war over policies that set body weight limits; in 1993, USAir required that a 5-foot-5-inch female attendant weigh no more than 138 pounds. Two of Nelson’s co-workers suffered from eating disorders promoted by years of shame from their employer. They died soon after.

“That was the product of those weigh-ins,” Nelson said, tears welling in her eyes. “Maybe they were prone to it or whatever, but the weigh-ins killed them. And I saw it firsthand.”

Then there was the sexual harassment.

“It wouldn’t have even crossed your mind to complain about any sexual advances by anyone—by passengers, by pilots, by anyone in the office,” Nelson said. “Most flight attendants thought we just had to deal with it. And we dealt with it by going internal, by building our union, and taking other actions … to gain respect for our roles.”

A week after the incident with her first paycheck, Nelson was recruited to do the union’s new-hire program and was soon named local communications chair. Six months later, the national union presented members with a contract proposal with United “that I thought stunk,” Nelson said. She led a charge to get it voted down; it passed by 51 percent nationally but, she said, “I did a really good job in Boston because we voted it down by 80 percent.”

“Instead of giving up, I got more involved and was a dissident voice in the union,” Nelson said. “Not really to tear the union down but to challenge the union.”

Nelson was off on Sept. 11, 2001, and had planned to spend the day doing union work. At 9:03 a.m., one of her usual flights to Los Angeles, United 175, collided with the south tower of the World Trade Center. She knew the entire crew, as well as two customer service representatives who were going on vacation. The experience crystallized Nelson’s view of flight attendants as essential guardians of public safety. In an effort to keep spreading the message, she became the union’s national communications director for the United chapter in 2002, which served as a platform to become vice president in 2011 and then president in 2014.

Nelson is reluctant to talk about the way she became president of AFA, probably because it involved ousting the cancer-stricken incumbent.

The incident, which has not been previously reported, is a messy part of Nelson’s carefully curated image. In the wake of a merger between U.S. Airways and American Airlines, Nelson participated in a coup against Veda Shook, who had been president for three years. U.S. Airways, whose employees were represented by Nelson and Shook’s union, was disappearing; American had its own union, the Association of Professional Flight Attendants, which was anticipated to represent the new combined unit.

Nelson objected fiercely, arguing that the new bargaining unit should be represented by AFA. It was an outlandish proposition, according to several people involved in the talks, given that the American union outnumbered the U.S. Airways flight attendants 2 to 1 and easily would have won a representation election.

In September 2013, the board passed a resolution that stripped Shook of her power to negotiate with the American Airlines union, effectively handing the reins to Nelson. The vote was unanimous, a board member at the time told me.

Shook, who is no longer involved in the union, was not eager to talk about her relationship with Nelson. “I was still working and undergoing chemotherapy and then all this other stuff happened,” Shook told me. “I didn’t see it coming until it was too late because I’d never met anyone like that before.”

According to Shook, Nelson convinced the board that Shook hadn’t fought hard enough for the U.S. Airways flight attendants. In the regularly scheduled election a few months later, Shook was defeated.

When I asked Nelson about this, she said other people put her up to it because Shook passed up an opportunity to get a better deal for the union. The AFA contract was better than the American Airlines union’s contract, Nelson said, and could have been used as a bargaining chip to get a better deal for all of the flight attendants.

“The leverage that we had was squandered,” Nelson said. “There were a lot of things where we weren’t fighting like we should, so people asked me to step up and fight, and it was probably one of the most difficult times in my life, actually. Painful. Really painful.”

“I took massive personal attacks,” she said. “So, hey, I know what that’s like, and I lived through it.”

The former board member, speaking on the condition of anonymity, corroborated Nelson’s account, saying the board had “lost confidence” in Shook’s leadership.

Others who were involved in the negotiations challenge Nelson’s version of events.

“It would be very disingenuous for them to say that their contract was better,” said Lenny Aurigemma, one of the negotiators for the American Airlines union. “We felt we got the best of both contracts. … They never made the money that we’re making now. Never, not even close.”

“I like Sara. I also like Veda,” said a person who worked for another transportation union that was involved in the merger “And I think a lot of people felt that Veda got a bad deal.”

“I don’t think it’s possible to talk about Sara’s history without saying she became president by pushing out the predecessor, because she’s not shy about taking on people who are in these offices,” this person added. “That’s the moral of the story here.”

Nelson’s talent for spotlighting the power of her union on hot-button progressive topics that have as much to do with embarrassing Trump as they do with labor issues was on sharp display in March. A Mesa Airlines flight attendant, who was a beneficiary of the DACA immigration program, was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement on an inbound flight from Mexico and detained for six weeks. Nelson mobilized her publicity machine upon learning of her plight. Hillary Clinton retweeted her, setting off a social media storm. Nelson and Mesa Airlines CEO Jonathan Ornstein, who knew each other from prior contract negotiations, spoke on the phone.

“It was like, you call the Democrats, I’ll call the Republicans, and let’s fix this,” said Ornstein.

The flight attendant was released within a day.

Ornstein and Nelson should be enemies. But behind closed doors, Nelson proved to be a skilled deal-maker, Ornstein said, and he gained respect for her at the outset when the two were able to finalize contract negotiations in a single meeting in 2017.

“You look at the labor movement right now and you’ve got what, 6 percent of the [private-sector] workforce now organized?” Ornstein said. “To me, that kind of creativity is what’s needed. The model needs to change, and I think Sara is the kind of person that could do that.”

Nelson’s opportunity to reshape the national movement is due in large part to the political wound Trump dealt to union leadership, specifically Trumka.

Three years ago, Trumka suffered embarrassment when portions of his membership—white workers galvanized by Trump’s protectionist trade message and promises of reviving manufacuturing—ignored the federation’s endorsement of Clinton and voted for Trump, rewarding the man accused of not paying his own workers with the largest percentage of union-household votes to a Republican since Ronald Reagan.

Trumka’s struggle to marshal the disparate factions of his coalition and present a unified voice has come at a precarious moment for unions, whose membership has declined inexorably in recent years. Last year, private and public sector unions represented 10.5 percent of the American workforce, down from their peak of 35 percent in 1954. The conservative majority on the Supreme Court also dealt a major blow to unions in 2018 when it ruled that public-sector unions may not charge members mandatory collective bargaining fees on the grounds that such fees violated members’ First Amendment rights.

Even the good news for the labor movement has come with a reminder of leadership’s weakening grip. More workers participated in major work stoppages in 2018 than in any year since 1986. But much of that increase came from the teachers strikes over pay and classroom funding in West Virginia, Oklahoma and Arizona. And those strikes — in deeply red states — were driven not by national unions but by grassroots Facebook groups created by local teachers.

Just who is in charge of the labor movement has forced a debate over what labor’s role should be in defeating Trump, or whether it should play any role at all. Trumka has said the AFL-CIO will evaluate all the candidates, including Trump, acknowledging that the president’s performance has been mixed for unions—good on trade, but bad on health care and wages.

Democrats want to step into that breach and rebuild the fabled “blue wall” in Midwestern swing states. But there is little agreement on how to accomplish that. Presidential candidates like Rep. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), who dropped out in October, have suggested that Democrats are ignoring unions by embracing far-left policy ideas like “Medicare for All.” Trumka—reflecting a divide in his membership—has said that the country “ultimately” needs to move to a single-payer system but that the value of union-won health care plans shouldn’t be lost in the process.

Nelson, by contrast, embodies a growing cross-section of union-minded Democrats who believe labor needs to stop apologizing for being liberal. Unions would have more success, she argues, if they embraced their activist roots.

Speaking to the Chicago Democratic Socialists in May—a speaking invitation it’s hard to imagine Trumka ever accepting—Nelson extolled radical labor leaders of yore. She spoke of A. Philip Randolph, the founder of the first black union, and his protégé, Bayard Rustin, who in 1963 organized 250,000 people for Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington, and Lucy Gonzales Parsons, who was thrust into activism after her husband was executed on false charges that he had carried out an attack at a labor demonstration in 1886.

“They were shot down at Homestead, Pennsylvania and in the hills of West Virginia,” Nelson said. “They were hanged for the Haymarket Affair in Chicago and beaten on an overpass near Detroit. … These activists thought it was important enough to stand up against all odds. … Today it’s our turn.”

“Our task,” Nelson added, “is to build a labor movement that sees itself truly as a labor movement — not just a collection of separate unions.”

“For years we outsourced our power while the bosses were outsourcing our jobs. We spent too much time trying to cut deals with the boss or build favor with politicians and too little time organizing members to fight for what we deserve. People think power is a limited resource, but using power builds power.”

This emboldened vision of union influence, say some labor activists, is not a breakaway faction—it’s actually a return to the mainstream of the movement.

“The new whitewashed idea that the labor movement is moderate—it’s not that,” said Amaya Smith, a former AFL-CIO communications director who now works for the National Partnership for Women and Families. “It’s a big family … You’re part of a historic movement that literally worked to fight against capitalism. It doesn’t get any more progressive than that.”

In that spirit, a growing number of progressives believe unions should do more to inject themselves into national conversations such as health care, climate change and immigration.

“I believe in a labor movement that leads the entire country, not just sits at a bargaining table advocating for the members of a particular union,” said Representative Andy Levin, a freshman Democrat from suburban Detroit.

That Democrats like Levin (who replaced his father, Representative Sander Levin, when he retired in 2018) agree with the progressive left on environmental issues and health care is significant, though he is careful to make clear he has not endorsed a possible successor for Trumka. In addition to representing a large swath of union auto workers, Levin is also a co-sponsor of the Green New Deal with Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“Climate change is a pants-on-fire crisis of such proportions and such immediacy that you literally can’t overstate how fast and how comprehensively we’ve got to deal with it,” Levin said. “If we do it fast and if we do it right, it’s going to create a tremendous number of jobs. And if we do it right it can be a lever to re-unionize America.”

Nelson knows that such policies—with their sky-high price tags—draw plenty of fire from political centrists who fear that anything that smacks of tax and spend socialism is simply playing into Trump’s hands. But Nelson is determined to reframe how unions look at issues like Medicare for All, which calls for abolishing private insurance in favor of a government program. Initially, Medicare for All was seen risky for the 2020 candidates to support because it could alienate union voters who had negotiated plans through collective bargaining. “You’ve worked like hell, you gave up wages for it,” former Vice President Joe Biden told the Iowa Federation of Labor convention this past summer, bashing the concept.

After former Maryland Rep. John Delaney argued that supporting Medicare for All would “get Trump reelected,” Nelson swooped in to back Sanders and Warren, two of its most prominent advocates. Government health care, she said, would allow unions to spend their time bargaining for higher wages and other benefits.

“It’s a huge drag on our bargaining,” Nelson told POLITICO in August. “So our message is: Get it off the table.”

Her pronouncement made the rounds online. Splinter, the now defunct liberal news site, proclaimed that “Not Every Union is Buying Into the Lies About Medicare For All.” Weeks later, the Massachusetts AFL-CIO passed a resolution to require that any candidate it endorses support Medicare for All, breaking with the national leadership.

Given the tepid support she enjoys from more conservative members of the AFL-CIO—particularly the building trades, where concern over eliminating oil and gas jobs runs deep—its hard to imagine Nelson ultimately succeeding Trumka. And even if she were to win, observers say Nelson would find it difficult to enact some of the controversial policies she supports. The AFL-CIO president has the unenviable task of managing a diverse array of 55 unions and developing positions that, in practice, are often a compromise.

“Historically, the AFL-CIO actions are taken around issues of the least common denominator because any union or group of unions can block a Green New Deal or Medicare for All from becoming adopted,” said Andy Stern, the former Service Employees International Union president who split with the labor federation in 2005. “So the AFL-CIO ends up being for building windmills because the building trades like building windmills and environmentalists like building windmills. That’s very different than supporting the candidates’ environmental plans or the Green New Deal.”

But winning Trumka’s seat might not be the only measure of success for Nelson. If she can link her wing of the labor movement to the political growndswell that is animating the 2020 contest—who knows? It might just topple a president.

“There are people who understand you can’t extract a social movement from an economic movement,” Nelson said. “They go together.”

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly spelled Cesar Chavez’s first name.