In Unity Park's shadow, a Greenville woman calculates the cost of her life

This is part of the Greenville News’ “The Cost of Unity” series, investigating unrecognized harm from revitalization efforts, including 2022's Unity Park, that are making historically Black neighborhoods unaffordable for the people who used to call them home. Our year of reporting — which included work with research partner Furman University — showed the staggering loss of Black residents from a city with one of the highest racial economic disparities in the Southeast. The full project launches Jan. 11 on greenvilleonline.com.

In the shadow of Greenville’s expanding skyline and brand-new Unity Park, Sharon Logan sat on the edge of the couch in her one-bedroom apartment.

She reached under the seat cushion for a rent notice among her pile of paperwork. This is the record of her life: pay stubs, landlord notices, court documents.

Her rent will double June 1, the document in her hand says, because she no longer qualifies for a federally subsidized rate. Her then-67-year-old husband, who is old enough to qualify, is in a nursing home. He is recovering from COVID-19.

Logan has done the cruel calculations countless times in recent days. No matter how many times she adds her income and subtracts the cost of her existence, the results are unmoving: She is always hundreds of dollars short of her new rent bill.

The federal rules for qualifying for subsidized housing are inflexible. Logan, then 59, is simply three years too young. That is the crux of her current problem, and when she looks out her apartment window, she can't find any solutions.

The Logans live in one of the few remaining affordable housing complexes near downtown and right next to Unity Park, the largest civic project in Greenville in decades. She can’t afford any of the places for rent or sale in her neighborhood of Southernside, a historically Black neighborhood.

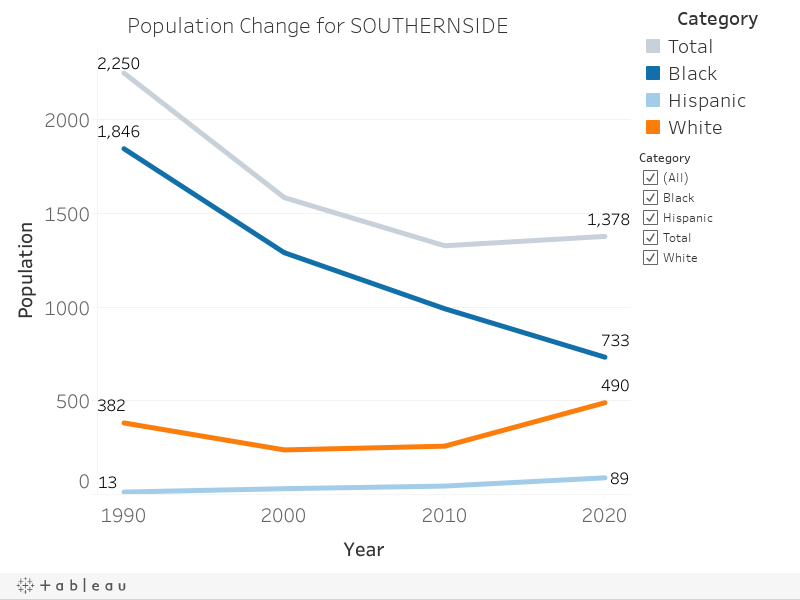

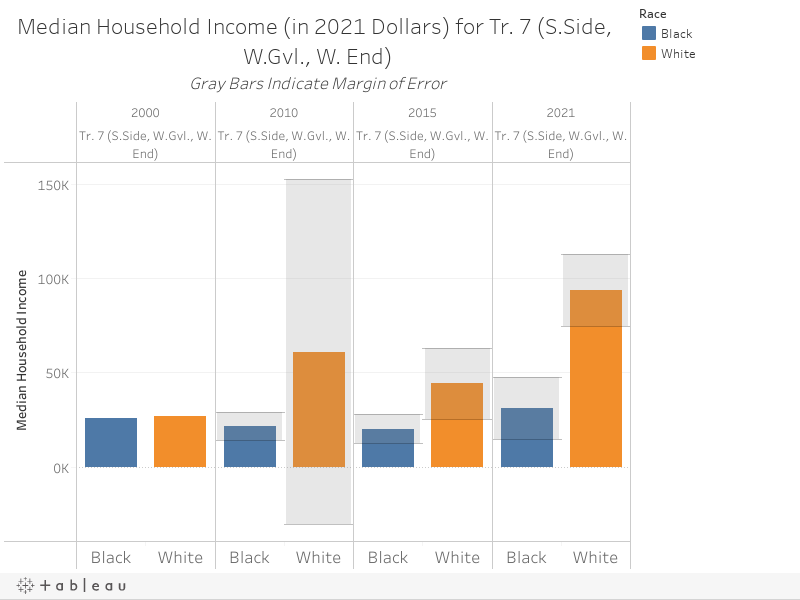

In the past 30 years, Southernside transformed into a significantly whiter and wealthier neighborhood. It’s seen a 60% decline in its Black population, according to research from Furman University. And the racial income divide is staggering. The median income for white households is 312% higher than that of Black households.

Household income (in 2021 dollars) by race for census tract 7 (West End, West Greenville, and Southernside Neighborhoods), 2000 to 2021.

Read the full Furman University study: An exploration of historic and current population shifts in the city of Greenville and surrounding Greenville County

Southernside houses are listed for sale at around a million dollars. Sold-out townhomes, just down the hill from Logan’s, hit the market with high six-figure prices. The new park will make it even harder for people like Logan to stay.

The park nestled near the city center features a playground, a dining and retail space, as well as access to greenways. It’s also the type of park likely to drive more gentrification, according to research published in Urban Studies Journal.

Logan, a Greenville native, has lived in Southernside for four years with her partner, Jerry. He caught her eye in a church pew over 20 years ago, and he’s barely left her sight since. A picture of the married couple, sporting their Pittsburgh Steelers jerseys, hangs in their bedroom at Brockwood Senior Housing.

Logan carefully maintains the apartment. It is an altar to family. Images of her nephews and nieces entirely border a living room wall. More frames line the kitchen counter. She hosted her loved ones for holiday meals. Christmas gift-giving, too. Every Wednesday, her church family gathered here for Bible study.

Jerry Logan worked four decades in construction and sanitation. Sharon Logan worked for years as a hospital cook before congestive heart failure and pain from chronic arthritis forced her to go on disability. The couple lived on about $1,500 a month in federal disability and other government benefits. At Brockwood, that was all they needed.

In January 2021, Jerry Logan contracted COVID-19. It set off a series of health issues, including multiple strokes.

Medicare paid for a hospital bed so he could recover at home, with Sharon Logan by his side. But his health worsened, and he now requires care at a nursing home. Logan said the hospital bed isn’t big enough for her and her grief.

The bed stays empty.

In late 2021, Brockwood management filed for eviction against the Logans.

The federal government subsidizes apartments here, and federal rules say at least one tenant in a Brockwood apartment must be at least 62 years old.

With the guidance of a pro-bono lawyer, she is fighting the eviction. “I have nowhere else to go,” she said.

Four days after Unity Park opened, a Bible sat open among her paperwork on the small table in her living room. “In the end, God has the final word,” Logan said from her couch. “I just don’t believe God wants me to be homeless.”

The first of the month was coming in eight days.

She would sleep on the couch that night, like she did every night, with her housing paperwork tucked under the cushions. Logan kept the documents there, she said, so she could pray over them as today turned into tomorrow.

And when she closed her eyes, she still held tightly to the hope that her Jerry would, one day, come home.

— Where are they now? Sharon Logan was evicted in November 2022 after not being able to pay her rent. She moved her possessions into a storage unit in Greenville. She moved in with her sister in Simpsonville, about 15 miles outside of the city. Logan began the new year looking for new places to live in Greenville. Jerry Logan continued to receive care at a nursing home in Greenville, and she wanted to live nearby.

He suffered more strokes in the first week of January 2023.

This article originally appeared on Greenville News: In Unity Park's shadow, a Greenville woman struggles to survive