University of Alabama graduate writes history of Tulsa Race Massacre

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

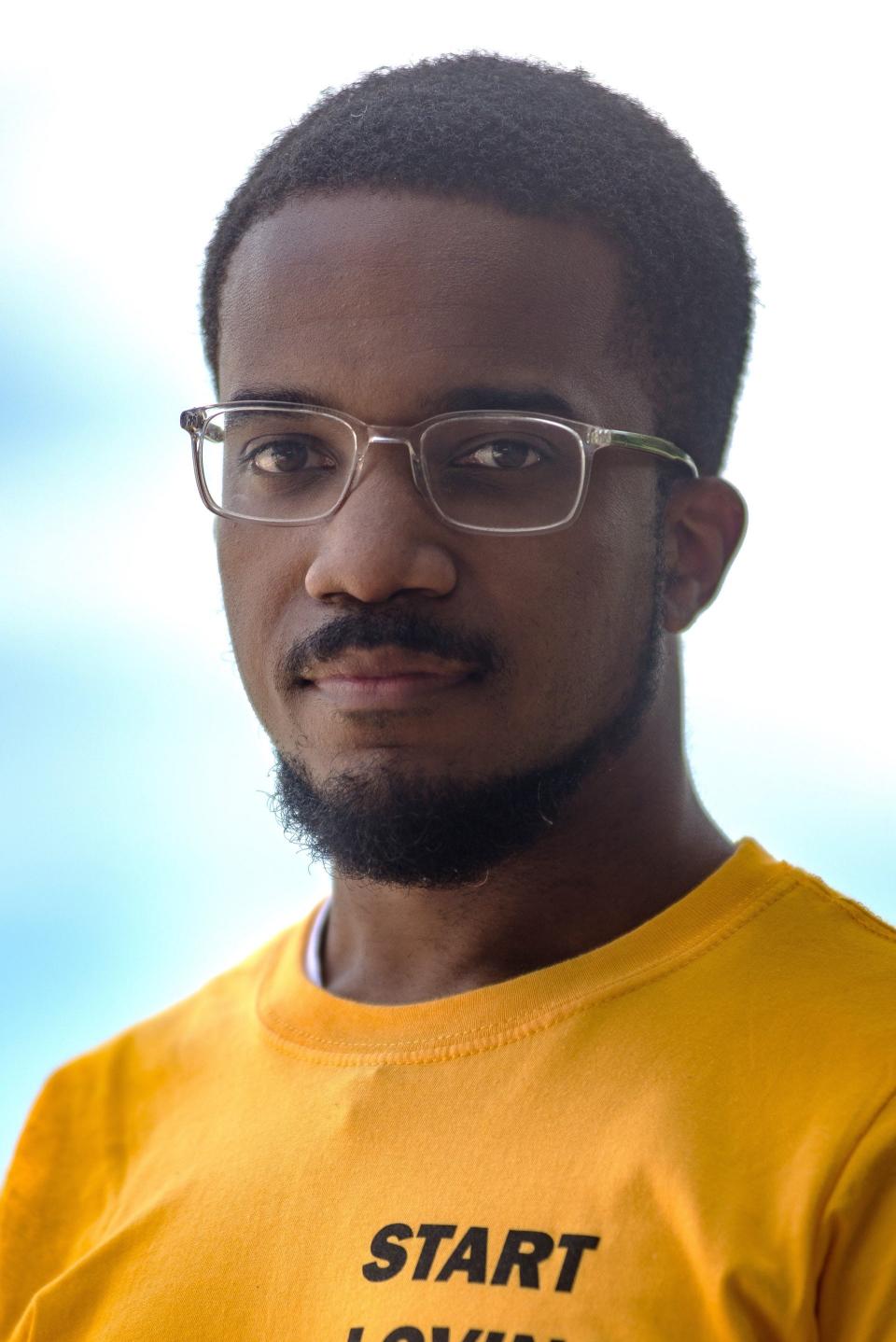

Though he grew up in Montgomery a lifelong reader and writer, later two-time editor-in-chief of University of Alabama campus newspaper the Crimson White, Victor Luckerson hadn't known much about Black Wall Street or the Tulsa Race Massacre until nearing that horrific 1921 event's centennial.

He wasn't alone in the knowledge gap, concerning two days of hideous carnage many sought to wipe from memory.

"It was very purposefully sort of buried in the years afterward," said Luckerson, a 2012 UA grad. "People totally clammed up about it, didn't talk about it for decades," trying to drown a vast event under time's tides.

In 2017, while working in Atlanta, Luckerson discovered friends, other people his age, didn't know anything about Black Wall Street, or the massacre. He knew some basics, but for a research kickstart, Googled the subject.

"There were only like five articles on the Internet. There was nothing. I couldn't find much, besides a scraggly Wikipedia entry," he said, laughing.

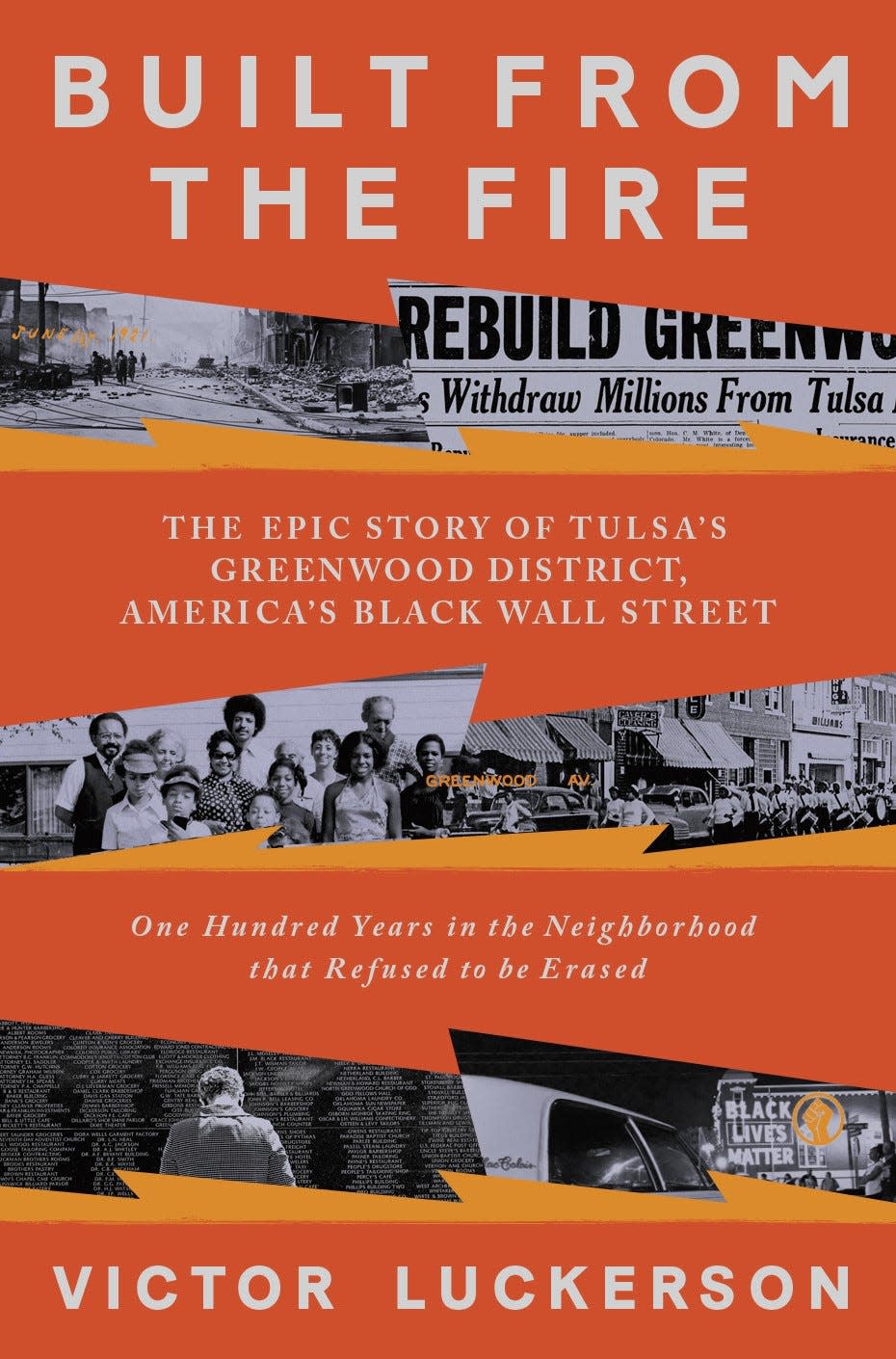

Luckerson researched and wrote a 6,000-word piece for The Ringer about commemorations of the May 31-June 1, 1921 white supremacist terrorist uprising, in 2017, and within the next year, moved to Tulsa to dig deeper. The result became his first book, "Built From the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa's Greenwood District, America's Black Wall Street."

Published in May by Random House, it's drawn glowing reviews and press from The New Yorker to The New York Times, which made it an editor's choice. He'll be returning to the alma mater Tuesday to discuss the work, at 5 p.m. in UA's Gorgas Library Yellowhammer Room. On Thursday he will be in his old hometown, 5:30 p.m. at New South Bookstore, 105 South Court St., Montgomery, for a similar discussion.

Black Wall Street burns

In the early 20th century, Tulsa, Oklahoma's thriving Greenwood community became known as Black Wall Street for its dynamic gatherings of growing families, large and small businesses, and its vivid nightlife. Greenwood glowed as a refuge for those seeking more prosperous lives outside the Jim Crow South.

But during that 1921 Memorial Day weekend, mobs of racists, some deputized and armed by Tulsa city officials, razed more than 35 blocks of Greenwood. More than 600 people were hospitalized, and 6,000 Black residents were held in various facilities, many for days.

Violence had been stirred by an incident between 19-year-old Dick Rowland, a Black shoe shiner, and a white 17-year-old woman, Sarah Page, who worked in a nearby building. Numerous versions of the encounter existed, but the most commonly repeated was of a misunderstanding, where Rowland accidentally stepped on her foot, inside the elevator she operated. As Page tottered off balance, Rowland apparently reached out to help her, and she screamed. A local newspaper stirred outrage with an inflammatory headline, encouraging readers to "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator."

Rowland was arrested and charged with assault. Rumors he would be lynched spread throughout the city. That night a gathering of about 75 Black men, some armed, came to the jail offering protection; the sheriff intervened and asked them to leave, saying he had the incident under control. As they left, an older white man approached one Black man, asking him to hand over his gun. When he refused, the older white man attempted to disarm the man, at which point the gun went off. Then, as the sheriff's reports wrote, "all hell broke loose."

Rolling gunfights spread throughout Greenwood. News of the violence drew white rioters who invaded Greenwood, looting and burning stores and homes, and killing men. Around noon June 1, the Oklahoma National Guard imposed martial law.

About 10,000 Black people were left homeless. Property damaged amounted to $1.5 million in real estate and $750,000 in personal property, roughly $37 million in today's dollars. Early records indicated 36 dead, though the 2001 Tulsa Reparations Coalition identified 39 dead. Other studies indicated related deaths may have ranged from 75 to as high as 300. Black Wall Street smoldered, and even as businesspeople and homeowners worked to rebuild from the ashes, various powers worked to deny them compensation.

Popular consciousness of Greenwood has risen this century, due in part to centennial commemorations, to Ta-Nehisi Coates' 2014 The Atlantic article "The Case for Reparations," and documentary films such as the 2014 "Hate Crimes in the Heartland."

The Tulsa Race Massacre took center spotlight within a pair of major TV series based on books of fiction, but using historical basis, in HBO's 2019 "Watchmen" and 2020 "Lovecraft Country." Depictions of violence were so vividly appalling, some early viewers thought the massacre arose from fiction writers' imaginations.

A century of Goodwins

Since his 2012 UA graduation, Luckerson has written for Time magazine and website The Ringer, with his writing and research appearing in Wired, Smithsonian, The New Yorker and The New York Times. In the process of compiling the Ringer article, Luckerson met Regina Goodwin, a state legislator whose family history in Greenwood extends back more than a century. They were visiting a museum's archives when she pointed out a photo of a dapper young man: "Oh, that's my grandfather."

The Goodwins moved to Greenwood in 1914. Seven years later, teen-aged son Ed, Regina's grandfather, hunkered down in a bathtub to avoid gunfire. Edward Goodwin Sr. grew up to be a prominent businessman. In 1937, he bought newspaper the Oklahoma Eagle, established in 1922 to replace the Black-owned Tulsa Star, one of the businesses burned in the massacre. The Goodwins still own and operate the Eagle.

That was a crucial "in" for Luckerson.

"This is this is a family of journalists," he said. "That makes them perhaps more understanding and trusting of my process. I was also uncovering a lot of facts about the family they didn't know, so I was able to come to them on my own devices."

One of Regina Goodwin's aunts, who lived in Nashville, owned a lot of memorabilia, but was very protective. Luckerson gained her trust emailing photos of the family she'd never seen.

"So I was kind of able to even the playing field; I wasn't just taking from them," he said.

Factual resources were available, Luckerson said, though not always easily accessible.

"In some sense, things were very actively buried; in some sense people just aren't actively poking around enough," he said. "Any journalist worth his salt knows you sometimes have to go to the courthouse and start badgering people."

Luckerson gained access to 5,000 lawsuits filed related to the massacre, but the information was on CD, so he had to obtain a disc reader to dig through. He found itemized lists of what people lost, how city and real estate companies tried to deny the victims compensation.

His book offers broader perspective than just tragedy, though, illustrating Greenwood before, immediately and long after the massacre, through those fighting to keep the community thriving, despite gentrification, urban renewal policies and other struggles.

"Black Wall Street was a story of Black success and solidarity, and that was my intention from the very beginning," he said "I wanted to tell a story that was factually true, but that had heart to it. I wanted that story to be about Greenwood, and not reduce it to the trauma."

George Daniels, UA associate professor in journalism and creative media, one of Luckerson's mentors, will guide Tuesday's book discussion. The event is free and open to all, and is planned to run from 5 to 6:30 p.m. For more, see www.vicluckerson.com.

Reach Mark Hughes Cobb at mark.cobb@tuscaloosanews.com.

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: University of Alabama graduate writes book about Tulsa Race Massacre