University of Alabama website shares historical stories of enslaved people on campus

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If the Moses who helped build and maintain the early University of Alabama campus was working today, he'd probably advertise himself as a master of all trades.

He plastered walls, mended chimneys, fixed outbuildings, planted trees and hedges, repaired fences, cleared pathways. Moses built a dredging machine to raise shells from the Black Warrior River bottom, constructed platforms and fixtures at the Maxwell Hall observatory, set up blackboards, installed fire grates in dormitories, and built a wall in Professor S.R. Stafford's potato cellar.

More: Black History Month: UA's Paul R. Jones Museum aims to elevate African-American art

He hauled sand and water, worked on telegraph fixtures, laid roofing shingles, and was beaten so badly by students he sometimes couldn't work.

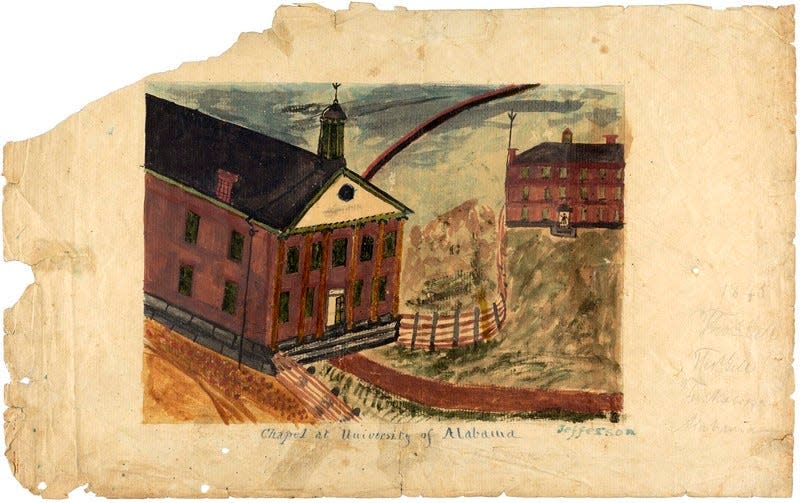

One stabbed Moses' arm with a fork. A party of drunken students assaulted his home, stole livestock he was raising, and made violent threats. Another time, students lured him to the Jefferson dorm — which Moses had helped roof ― and beat him with sticks, before whipping him in front of all present.

Then-UA President Basil Manly, who led UA from 1837 to 1855, was outraged by how students harmed Moses. They were disrespecting the president; disrespecting his property.

Moses had been bought for $700 on Jan. 3, 1845, at about 28 years old, becoming one of a small number of men directly enslaved by the university.

He remained property of the institution until sold, sometime in the 1850s, to Stafford, so he may have continued to work on campus a while, until Stafford and wife Maria took their 20 enslaved people and left to run the Alabama Female Institute, a college for white women in Tuscaloosa. Professors routinely kept enslaved people on campus, though students were not allowed to bring their families' enslaved people.

No disrespect is intended by calling this hard-working, long-suffering man simply Moses. He may not have had a second name. There is a Moses Stafford — some slaves took the last names of their owners — listed in the 1866 census' "Colored Population" for Tuscaloosa County.

As is so much about the history of enslaved people, on the UA campus and elsewhere, records can be "frustratingly vague," as Jenny Shaw wrote in the narrative about Moses for website "The History of Enslaved People at UA, 1828-1865." Shaw, an associate professor of history at UA since 2009, led a faculty work group assembled to compile and publish the scholarship.

A task force to study race, slavery and civil rights history at UA was established in 2019, following a faculty senate resolution to that end the previous year. Though the pandemic delayed progress, the work group ― Shaw joined by former graduate students Katharine Buckley in library and information studies, Briana Weaver in history, and Valery West in gender and race studies — massed to pull together reams of resources. It's in alliance with more than 100 universities in the United States, Canada, Colombia, Scotland, Ireland and England, all working on projects regarding slavery at their respective institutions.

The site is in fact an aggregation of decades of work at the University of Alabama that "provided a space on campus for people to address these questions," Shaw said.

Ground had been laid by UA history chair Joshua Rothman, who put forth the resolution apologizing for UA's role in slavery; Hilary Green, in gender and race studies at UA before moving on to Davidson College, who created the Hallowed Grounds Project; and UA law professor Alfred Brophy, who wrote the 2016 "University, Court, and Slave: Pro-slavery Thought in Southern Colleges and Courts, and the Coming of Civil War," from Oxford University Press. Those and other "further reading" references can be found linked on the site.

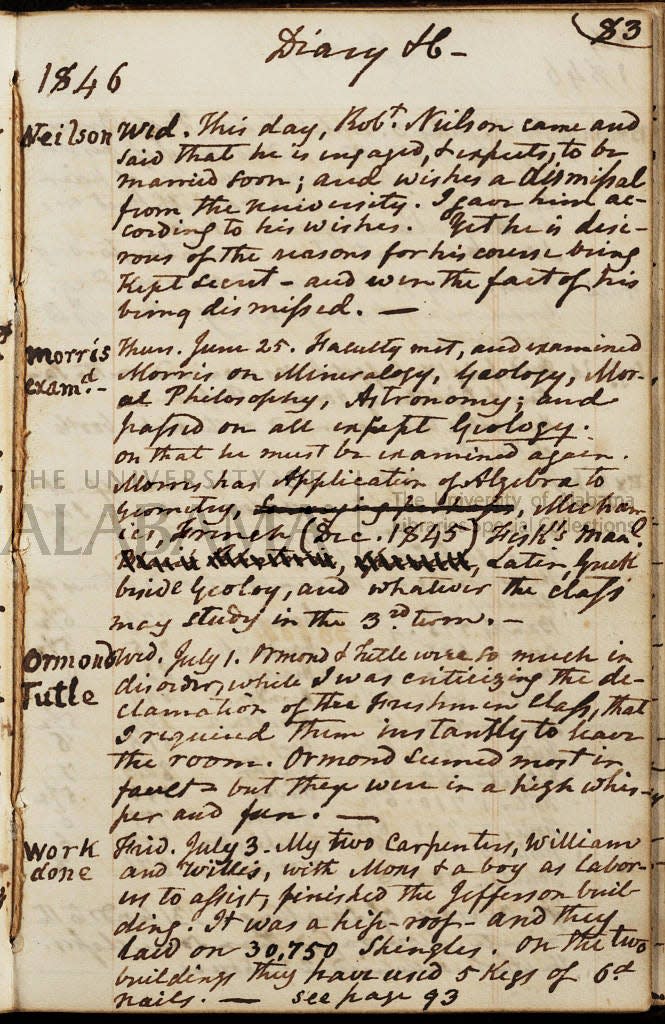

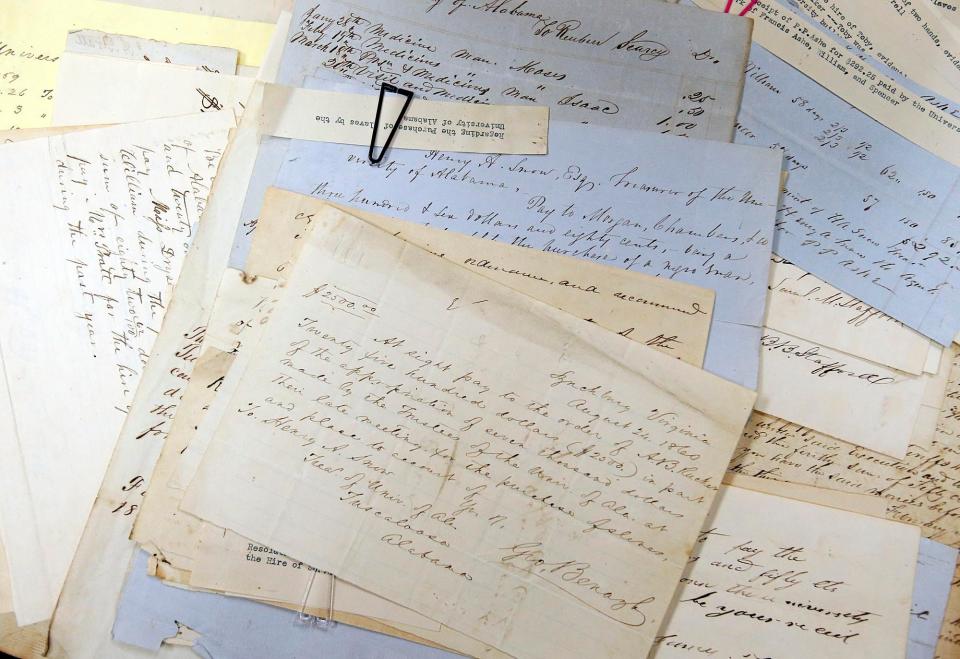

The group sought to find every reference to slavery in sometimes difficult to read paper: board of trustees minutes, faculty minutes, and the diaries of UA presidents Manly and Landon Garland, among them.

"When we began, I don't think we knew the website would be the result," Shaw said, "but we needed a platform for all this data, this information."

Whereas broader historical efforts had talked about the roles of slaves on campus, Green's work with Hallowed Grounds examined the individuals.

"Hers was the first to really center on enslaved people," Shaw said.

The team identified 164 enslaved people who lived and worked on campus, some of them hired out by Tuscaloosa slave owners, who perhaps didn't require all the skills one of them might possess.

Extrapolation was a necessity, working from the outside in, as most of the enslaved did not leave written memories, or at least few that have been found. Studying sometimes-tiny receipts, scribbled on paper, for tools, clothing and food, the team could help identify what kinds of jobs that person would have done.

"Starting with one of Manly's diaries, we found lists of tools that Moses was going to use, a chisel, a grubbing hoe," she said. "Those were things that belonged to UA, but were listed as in the possession of Moses, who did so many different things on campus.

"One of the reasons I was leading the research group, I am a historian of slavery so I have the tools to be able to read things from context.

"It's challenging. You have to remember the bias in the source that has been created. That helps you, because you can work with that. You can ask yourself simply what this event might have looked like from Moses' position?"

Happily, some of UA's early records were already digitized. All are digitized now, for ease of reading, though the original manuscripts are also available for study, for those who care to view 19th century handwriting.

The site remains a work in progress, though it is up and available for all to see. More may be added as the studies continue.

"There's still just so much we don't know," Shaw said. "At least to this point, we have not identified (any enslaved person) who left anything in their own words," with the exception of Peter Madary, one of four — with Moses, Lydia and Binkey — for whom the site has compiled longer narratives.

Reach Mark Hughes Cobb at mark.cobb@tuscaloosanews.com.

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: UA compiles stories of enslaved people on campus, pre-Civil War