How the University of Iowa is handling steep increase in requests for disability accommodations

For some, the substantial increase over time in requests for disability accommodations at the University of Iowa is no surprise.

"By the time you get to college and you hear that, 'Hey, there's accommodations,' it's like, 'Oh, thank God, I'm definitely going to use them,'" said Abbie Steuhm, a UI student advocate for students with disabilities.

Like any disability, accommodations for one student won't be the same as those for the next. They could range from requesting class materials with enlarged print for people with low vision, specific types of furniture in a classroom to make room for a wheelchair, or extended test time to account for an insulin shot.

Regardless of the specifics, the increase in requests for such accommodations is being felt at colleges nationally. Advocates say the trend could represent a shift in thinking about disability — more people being willing to request accommodations, not more people needing them — that points to a need for more accessibility beyond university walls.

In 2021, UI recorded 3,784 individual student accommodations among roughly 30,000 students. That represents an 80% increase over a decade prior, when in 2011 there were 2,106 requests.

The number of disabilities recorded among students has also risen about 77% in the same time frame, despite enrollment remaining relatively steady.

Catherine Johnson, executive director of Disability Rights Iowa, said accommodations are in some cases still thought of as a "special treatment."

But she likes to reframe that idea, saying it's anyone's right under federal law to ask to do schooling, or work, in a way that allows them to be successful.

“What is unique, and I think really promising about institutions of higher education, is the purpose of the institution is to provide education and growth and broaden people's perspectives," Johnson said in an interview. "So I think that universities have a unique opportunity to really teach what it means when we say ‘disability inclusion.’”

This spring, nearly a third of tests at UI center used accommodations

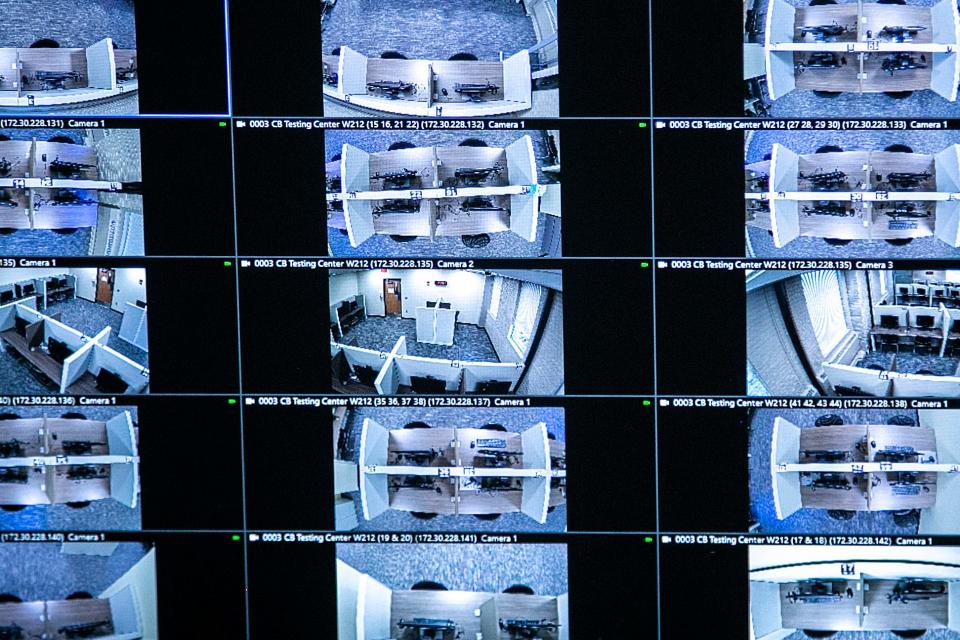

Much thought goes into administering a test on a university campus: Ensuring students flip brimmed hats backwards, take cases off of calculators and put their phones in a locker are some examples used just to deter cheating.

But there's more to it. A student might need to bring snacks into the testing area if they have diabetes — but only in a clear bag. They might need a reduced-distraction space, but they still need to be within the field of vision of the test proctors.

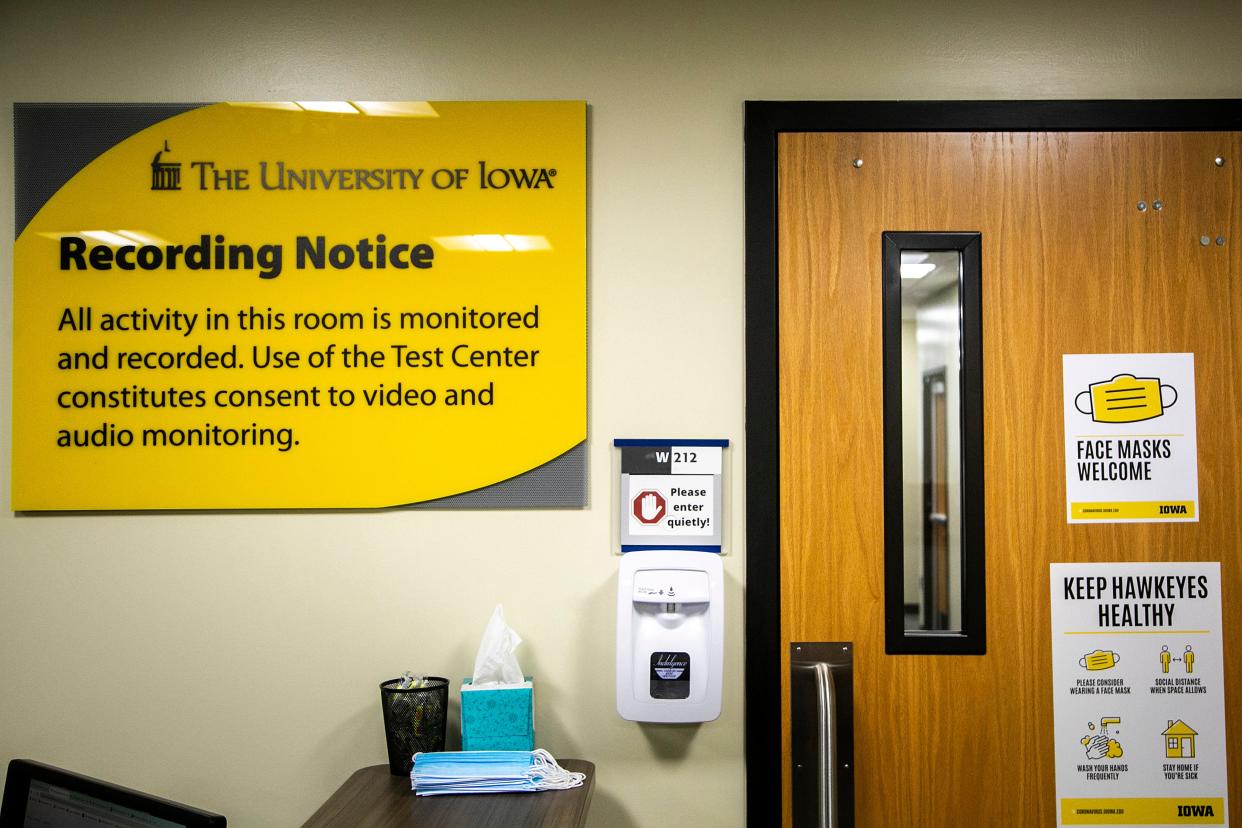

Navigating those situations is the day-to-day job of the people who operate UI's North Campus Test Center. The space used for administering exams across UI opened on the main university campus just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, in part due to the increase in accommodation requests.

This spring finals season, the testing center was packed, despite keeping its doors open from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. The 48-seat space hosted more than 6,000 tests last spring semester, with 30.5% using some sort of accommodation through Student Disability Services.

To receive an accommodation, students apply through the SDS office and provide documentation from a medical professional. If they are approved, they work with their professor to figure out the specifics of the accommodation for the class they are taking. SDS staff aid in that process as needed.

Steuhm is the incoming president of the roughly 100-member group called UI Students for Disability Advocacy and Awareness. They say the increase in accommodation requests isn't a surprise — especially because of the internet, younger people are far more willing to talk about diagnoses, or about going to therapy.

Students are sometimes concerned about the process of working with professors to implement the accommodations, Steuhm said. In some cases, they have heard about professors not taking the requests seriously, or not following through with them.

Ensuring that process goes smoothly — and holding professors accountable if they don't follow requests — is one thing Steuhm would like to see happen as the requests become more common.

But they also say it would be better to make the average space on campus, or elsewhere, more generally accessible in the first place.

"Even structuring classrooms to come pre-accommodated," they said. "Just doing that before the students even enter the classroom in an attempt to normalize it, and not point anybody out."

Definition of 'disability' could be expanding, with goal of offering more protection

Not all students with disabilities will report them to UI, nor will all of those students request accommodations. Bill Loyd Jr., the director of a UI transition program for 18- to 25-year-olds with intellectual, cognitive and learning disabilities, points out that universal accessibility can especially benefit those students.

The "UI REACH" program began in 2008 with a class of 18 students. It expects to hit a record of 70 students in the fall 2022 semester.

The program pushes for the use of the "universal design for learning," or setting up a class with the idea that there's no one-size-fits-all way people learn new concepts.

In a classroom, that could mean a professor doesn't just give an oral lecture, but supplements it with visual information in a PowerPoint or handout. Instead of just giving an essay for finals, they could provide several options like hands-on projects or oral reports, as that might better fit with the way a student learns.

Johnson, with Disability Rights Iowa, points out that most students in college today have grown up in a world with the Americans with Disabilities Act. When that federal law passed in 1990, the average person probably had a narrower idea of what "disability" means than today.

“We as a society have really only recently, I think, began to realize Congress’s intent of the breadth of disability within the ADA," Johnson said. "The intent is to include as many different types of disabilities for protection and from disability discrimination, and also to ask for accommodations.”

Things that people might not think of are included in the ADA, she said — mental health conditions, strokes, asthma, diabetes, cancer, reproductive issues and digestive are some examples.

She said the pandemic called attention for the broader population about mental health. But the topic of addressing people's issues with mental health — especially popular on college campuses — predated COVID-19, she said.

UI tracks the number of singular "disabilities" reported to the university, not the number of students who identify as having one or more. The data are sorted by learning, health, psychiatric, mobility and sensory disabilities.

The number of "psychiatric disabilities" reported at UI has risen substantially in the past two decades. In 2021, 429 were reported; in 2002, 80.

Johnson expects the number of students at college campuses requesting accommodations to continue increasing. That's because she points to data showing one in four Americans have some form of disability.

She argues that's why it's important for institutions, including UI, to be proactive in thinking about how to make day-to-day life accessible for all.

“From my perspective, this is good; I think the schools should respond in the same way, that this is good. We want students to go on and realize their dreams," she said.

Cleo Krejci covers education for the Iowa City Press-Citizen. You can reach her at ckrejci@press-citizen.com.

This article originally appeared on Iowa City Press-Citizen: University of Iowa sees growth in student disability accommodations