University of Michigan professor's book on national anthem sets us straight

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As Americans, we are united in knowing lots of things about “The Star Spangled Banner.” It appears that many of them are wrong.

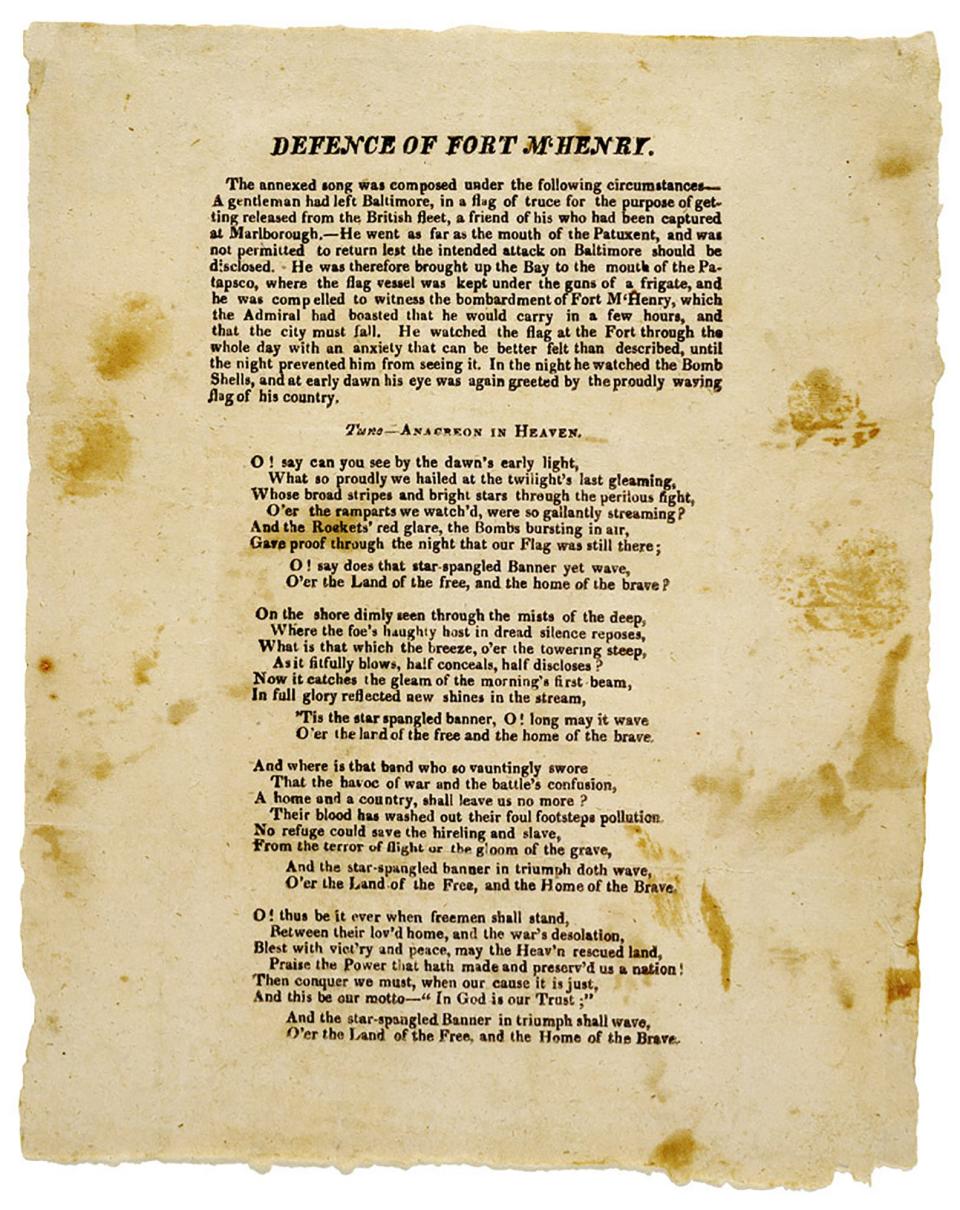

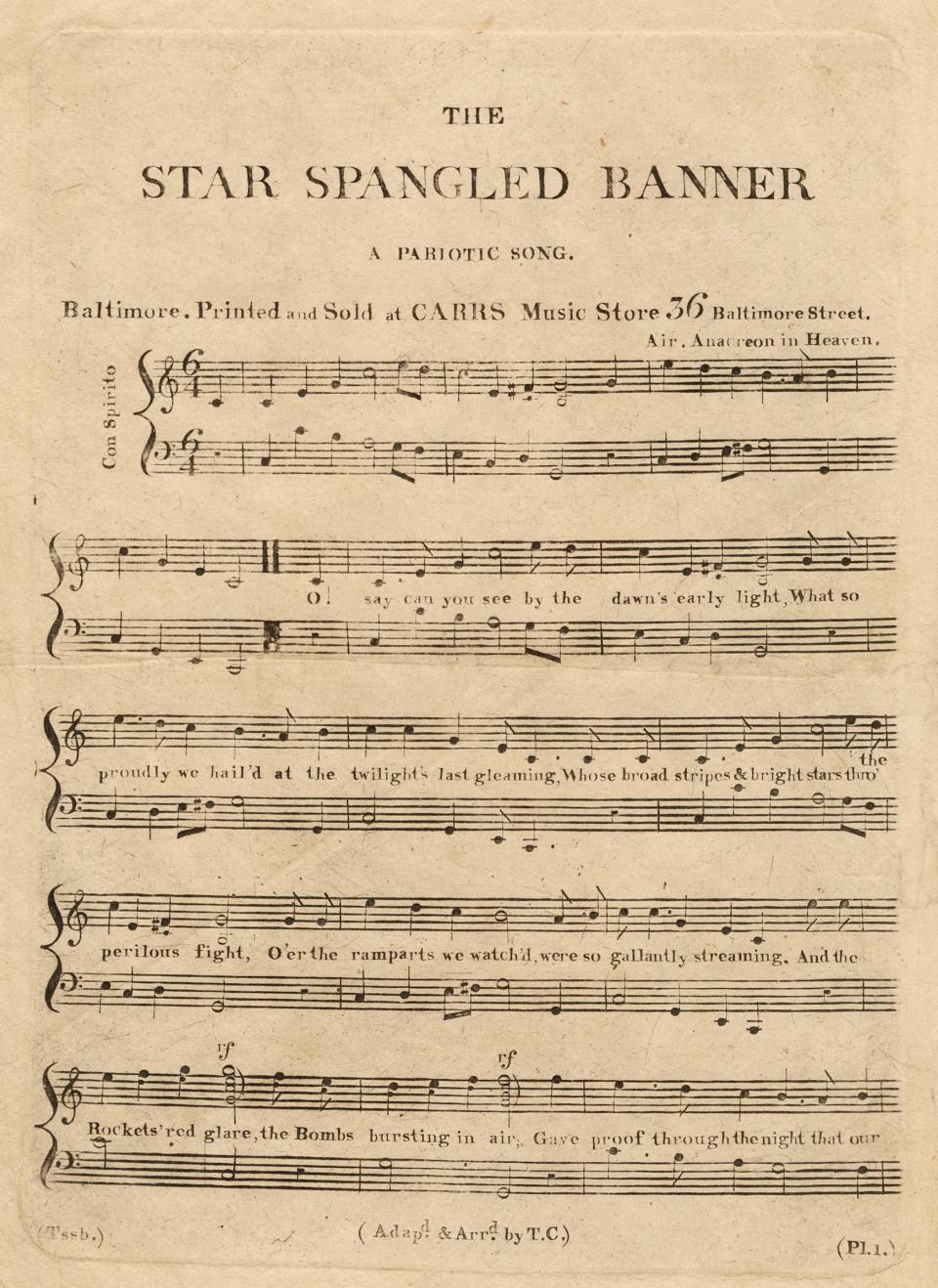

To start with, Francis Scott Key's poem was not serendipitously found at a later date to fit a melody favored by English drunks. It was written to match "The Anacreontic Song," just like 580 other songs that didn't become the national anthem.

Also, says University of Michigan musicology professor Mark Clague, we tend to forget that the verse we sing ends in a question mark, not a period. It's not saluting us for our plucky resolve; rather, it's asking whether we have the nerve to endure.

Furthermore, he contends, the anthem isn't terribly difficult musically: "As long as you start low enough in your vocal range, you can pull it off."

We are universally correct, he says, in regarding Whitney Houston's rendition at the 1991 Super Bowl as a masterpiece — but we don't realize that without Jose Feliciano's soulful and misunderstood performance at Tiger Stadium during the 1968 World Series, other versions still might be more boring than soaring.

More: Time may be nearly up for 250-year-old elm tree at Elmwood Cemetery

More: Remote lodge at tippy-top of the U.P. is now official dark sky park

As for that problematic, rarely heard third verse, with its reference to the spilled blood of "the hireling and slave," Clague suspects that "slave" doesn't mean what a logical person in 2022 would assume it does.

Likewise, Key isn't necessarily what we think he was, even though he owned slaves. As an attorney, he prosecuted abolitionists, but “he also fought on behalf of Black Americans fighting for their freedom in court," Clague says. "His legalwork resulted in the freedom of at least 189 people.”

And, while Key would be flattered that we sing "The Star-Spangled Banner" almost to the exclusion of every other patriotic tune, "he'd also think it was crazy."

Clague outlines all of that and much, much more in a vibrantly readable new book, "O Say Can You Hear? A Cultural Biography of 'The Star-Spangled Banner,'" (W.W. Norton & Co., $28.95).

To his surprise and enormous delight, the book wound up on the cover of last week's New York Times Book Review, with an accompanying rave from Peter Sagal of NPR's "Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me!"

Sagal called it "immensely interesting," a status Clague achieved largely by treating the anthem as a historical figure in its own right. Like Key, who jotted down his poem after watching British ships bombard Fort McHenry two years into the War of 1812, it's been a witness to history.

Francis Scott's key question

Clague, 55, grew up in Ann Arbor, meaning he’s “been a Wolverines fan basically since I was a toddler.”

He majored in bassoon performance and the history of art at U-M , and was good enough with his instrument to fill in with the Chicago Symphony while he was earning advanced degrees at the University of Chicago.

He and his wife, conductor Laura Jackson, have three college-student children who assisted in the writing process by telling him when they found a passage confusing or dull.

“One of the things I bring to the book,” he says, “is a sensibility as a musician as well as a historian.”

In both roles, he appreciates how Feliciano begat Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock who begat Motown’s Marvin Gaye at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, turning the anthem’s 3/4 time into 4/4 and transforming a waltz to a march — or, “a waltz to a hymn.”

That option didn't exist when Key put quill to paper. Sheet music was not readily printable or available at nearby strip malls, so new songs frequently piggy-backed on established tunes.

Key's goal was not to write a song to be performed centuries later: "Nobody has ever written a successful anthem," Clague notes, "that starts with, 'I'm going to write an anthem today.'"

Rather, Key was calling on the citizens of a nation less than 40 years old "to answer the question, 'Are we still free? Are we brave enough to live up to our ideals?'"

Colin Kaepernick, he suggests, was asking the same thing when he knelt on NFL sidelines as the anthem echoed across stadiums.

"To me," Clague says, "patriotism and protest are both part of the history of the anthem."

Often, they're the same thing.

'True to ritual'

"The Star-Spangled Banner" began its transition from song to national anthem during the Civil War, Clague says.

The volume was turned up again during World War I, as anthems and flags helped sort out which countries were on the side of right and goodness and which were in the other trench.

By the time Congress codified “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1931, “it was just recognizing what was already true in ritual.”

Clague began teaching the anthem in musicology classes in 2004 and started research for the book six years later.

It wasn't until the Kaepernick firestorm, he concedes, that he started digging into the third verse, and he was stunned to learn that "no one had really looked at the word 'slave' in any depth. It's remarkable. I mean, the song has been around for 208 years."

His conclusion is not flattering to Key or his target audience.

“Hirelings and slaves,” he believes, refers to the British attackers, who were salaried soldiers while the Americans were volunteers. Doing the bidding of the king made them slaves.

“It takes an incredible myopia to not see this as people who were actually held captive as laborers,” he says, but obtuseness was a benefit of being a white American male in 1814.

As he acknowledges, other historians hold that Key was referencing the Colonial Marines, liberated Blacks who volunteered with the British.

Either way, it's a verse that does not endear itself to millions of Americans. So as a trained academician with more than a decade of study to fall back on, Clague has a suggestion:

Whack it.

We only sing the first verse anyway, and the same sort of legislative act that made the song the national anthem could shorten it from four verses to three.

No muss, no fuss, and one thing we all know to be true is that the author isn't around to complain.

Neal Rubin still sings along to "The Star-Spangled Banner" at ballgames, but he lets the sopranos in the crowd handle the high notes. Reach him at NARubin@freepress.com, or follow him on Twitter at @nealrubin_dn.

You can subscribe to the Free Press for a song. Just click here.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: University of Michigan's Mark Clague writes book on national anthem