How to unlock the traditional science of Indigenous Australians

The divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians is still undeniably wide, with Indigenous Australians consistently losing out in health, employment, incarceration, life expectancy and education.

Given the disadvantages faced by Indigenous Australians, it follows that they’re also under-represented in science fields. But according to some, it's time to recognise that science is actually central to Indigenous culture and survival.

"When we talk about Aboriginal science, don’t forget we're the ones who turned a stick in to a boomerang, without aeronautical engineering degrees," Jim Walker, Former Manager of Indigenous Engagement at CSIRO (Australia’s federal agency for scientific research) said at a panel discussion at Brisbane’s World Science Festival in March.

Walker is from the Iman and Gureng Gureng peoples of Central Queensland and he was joined by two other Indigenous Australians who work in science, to discuss the concept of Aboriginal science and its relationship with its Western counterpart.

The take-away? This valuable body of ancient knowledge, gathered from thousands of years of learning, should not be simply appropriated.

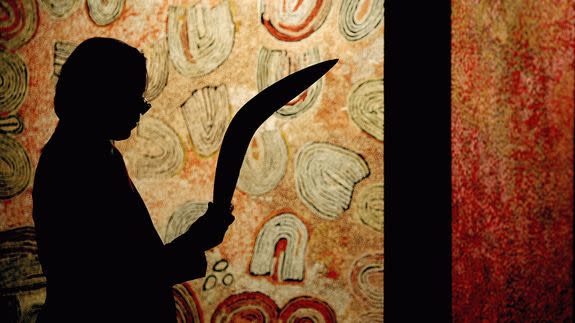

Image: De Agostini/Getty Images

Most Aboriginal science relates to the natural environment. That makes sense seeing as Indigenous Australians lived on the land for at least 50,000 years before colonisers arrived in the late 18th century; thousands of years of study and experimentation have informed Aboriginal understanding of the factors that impact the land, especially water flow and animal populations.

Panelist John Locke, who specialises in the connection between Aboriginal culture and landscapes, said a deep affinity for environment runs through all aspects of indigenous culture and it’s not just unique to Indigenous Australians. "I always use the example that Inuits have 40 different words for snow — that illustrates that very connected feeling they have with the landscape," he said.

Western science has been slow to embrace indigenous bodies of environmental knowledge. According to the panel, that might be down to distinct communication styles. Aboriginal knowledge is often woven in to traditional beliefs or "Dreamings," which are generally passed on orally through stories, rather than on charts and in research papers.

Walker gave the example that his culture group used to tell children a beast called Mundigai lived in the cold water of their area. As a child, as soon as he swam in to cold water, he would retreat to the warmer areas. In fact, there was no Mundigai and the adults were using their knowledge that the deep water was always colder than shallow areas, to keep children safe from downing.

"[Aboriginal science] is not empirical," said Mibu Fischer, a descendent of the Noonuccal, Ngugi and Gorenpul clans of Quandamooka in South East Queensland. "It's not full of mathematical information and that’s what a lot of scientists want [for example] they want the exact number of turtles in that area at a certain time and that’s not what indigenous science is… it's an understanding between people and environment," she said.

Image: De Agostini/Getty Images

There’s more to Aboriginal science than an established body of knowledge, according to Walker.

"We look at the world differently," he said. "It's a way of problem solving that indigenous peoples can bring to science. Where you’ve got a diversity of cultures in your group, people will look at problems with a different point of view and that brings a richness to discovery and a richness to innovation."

As Fischer, Walker and Locke exemplify, a relationship between Aboriginal and western science is now developing. That’s great news for western science, but might not be so great for the traditional custodians of these Indigenous learnings. The panel members shared strong hesitations about integrating their traditional knowledge into the Western system.

Locke warned that disclosure of Aboriginal science needs to respect the rights of the owners of that intellectual property. "There needs to be protection around that knowledge and the use of that knowledge," he said. Locke pointed out that a lot of Aboriginal learnings carry significant cultural weight and said, "You need to protect that sacred and secret knowledge."

This raises important questions about intellectual property rights and traditional knowledge.

The underlying idea behind cultural stories and knowledge isn’t protected by under intellectual property laws. And even if it was, would information rights rest with previous, current or future members of the group? How do you quantify the value of communal information when its disclosure will deny future generations’ their stake in it? Locke says these kinds of issues — as complex as they are — need to be worked through before western science can tap in to the knowledge reserves of its Aboriginal counterpart.

But Fischer proposes a different approach altogether. "I'm not really sure if [Aboriginal science] has to be used to benefit western science," she said. Fischer is from "salt water" and said her heritage has been an important factor in her research into sustainable marine resources and has also helped her communicate and learn from other Indigenous Australians. But she said she doesn’t see a need to connect the two areas of Aboriginal and western science. Instead she wants to see Indigenous knowledge recognised and respected as a separate, distinct system.

"Why can’t Indigenous be a stand alone science system?" she asked. "Why do we always have to bring it back to the western way, just because we’re in Australia?"