Unsafe stairs. Leaking closets. No walls. As Paterson schools crumble, students struggle

Aside from the occasional rustle of paper and tap of keyboards, silence permeated Louise Hanania’s Paterson classroom. Her fifth graders hunched over their laptops, absorbed in a writing assignment.

Then the rattling of a tambourine shattered the silence. The jarring disruption came from behind a line of cabinets, bookshelves and corkboard.

The jangling was quickly joined by a piercing voice. “Red chair!” a woman trilled. “Orange basket! Green plant!”

On the other side of the cabinets, in the same room Hanania and her students were using, sat another class, listening to another teacher. These students, Spanish-speaking second graders, were learning English to the beat of the tambourine.

Hanania’s pupils didn’t flinch. Not at first. None of the children craned their necks.

But as the other teacher continued to strike the tambourine to the words she chirped — a technique to help non-English speakers learn — concentration among Hanania’s students frayed. A boy tapped his foot in time. A girl hummed along. Students giggled and twisted in their seats.

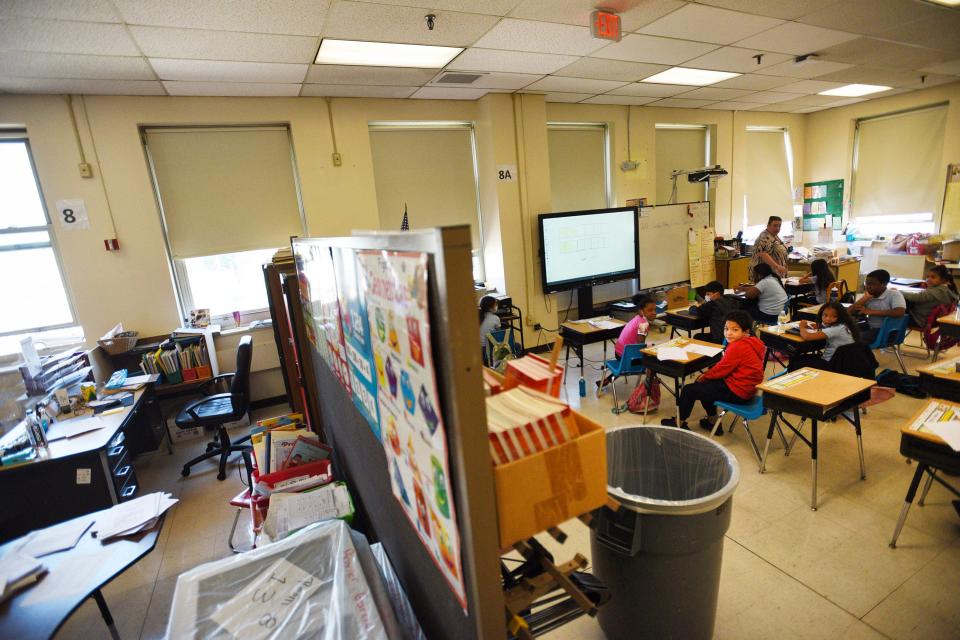

The distraction occurred because Hanania and her students must share their classroom space with other groups of students at Paterson’s Roberto Clemente elementary school. Their large room is divided into four learning spaces by makeshift partitions of furniture that reach only about seven feet up from the floor, instead of walls.

“It’s really difficult,” Hanania said. Some of her students have attention deficit disorder. But even for those who don’t, “it’s hard to concentrate. You’re constantly refocusing. They have to be reminded, ‘We’re not in that class.’”

In this first installment of a three-part series called “Crumbling Schools, Struggling Students,” NorthJersey.com focuses on the staggering infrastructure needs of an overburdened urban school district that lacks the property tax base — and therefore the financial resources — to pay for desperately needed renovations and new school construction. We look at how it got to this point, despite the creation of a historic state construction agency and an infusion of hundreds of millions of dollars in state aid over 20 years, funded by taxpayers.

NorthJersey.com examined years of financial data and facilities reports, interviewed experts across the country, and talked with Paterson teachers, district officials and families about the impact of infrastructure deficits on the district’s students.

In the coming weeks we will introduce you to some of the teachers and families directly affected and lay out the potential solutions suggested by experts to address the school facilities crisis plaguing not only Paterson, but burdened districts nationwide.

Learning environment crucial to student success

Numerous studies show that students' learning environment is crucial to their academic success, health and development.

Noisy classrooms can increase stress, behavioral problems and hyperactivity in children. A study of 73 elementary schools in Florida, for instance, found that students underperformed on achievement tests in classes with louder heating and cooling systems.

Exposure to indoor air pollutants can cause asthma-like symptoms in children, and asthma is a leading cause of missing school due to chronic illness. Studies have shown that university students found it more difficult to complete simple and complex tasks when the room was too hot or too cold.

Despite hundreds of millions of dollars of investment by New Jersey over the past two decades, Paterson Public Schools — which educates nearly 25,000 students in more than 40 school buildings — remains in desperate need of new schools and extensive repairs to its aging buildings.

And Paterson’s crumbling infrastructure mirrors a larger national problem. Half of public school districts across the country need to restore or replace major systems in their schools, including heating, plumbing and ventilation, according to a 2020 study from the Government Accountability Office.

Trying to learn in an old mill

Paterson uses 17 school buildings that are more than a century old, and with age come such health hazards as asbestos, lead and mold. Schools are so crowded that some classes take place in portable trailers.

Then there is Roberto Clemente, built in the 1920s to be not a school, but a mill. It went through multiple reincarnations, as a metal trade school and then — half a century later — as a K-5 elementary school. Today it is ill-suited for the needs of 21st-century learning and hard-pressed to meet modern safety standards.

'I can effect change': Abbassi pledges to listen to Paterson voices in police takeover

Speaking before 1,100 grads: Paterson student who wants to 'make a social impact' will speak at college graduation

The structure’s drawbacks have been obvious for decades now. Kimberly Lucero, 28, still remembers how her fourth grade class shared a room in Roberto Clemente’s basement with a bilingual class. One day, as her class broke into groups to discuss a passage, another teacher barged into the room to complain that the students were too loud.

Nearly two decades later, Lucero’s 11-year-old daughter, Kylee Nova, experiences the same deficiencies at Roberto Clemente.

“Sometimes I hear the other class singing the alphabet,” Kylee said. “So I start singing ‘Silence’ and everyone else starts singing along.”

Lucero remembers how hard it was to focus when she took tests at Roberto Clemente, and she worries for her daughter.

“She gets distracted easily, so I can imagine — is she really learning?” Lucero said. “I know it’s really hard, because I went through it.”

Roberto Clemente needs more than classroom walls.

There is no playground, just blocky steps, once perhaps intended to be an outdoor stage. Children draw with chalk or play tag on a small plot of often slippery asphalt enclosed by a chain-link fence. Staff members routinely clean up broken glass and syringes, Hanania said.

When torrential rain from Tropical Storm Ida flooded the basement cafeteria, waste bubbled up out of toilets and sinks because the city’s overwhelmed sewer and stormwater systems use the same pipes. The district spent about $166,000 to remove damaged sheetrock, look for mold, sanitize the area and replace ruined furniture.

When the cafeteria is out of commission or used for testing, students eat quietly at their desks so they don’t disturb adjoining classes, even though this is the period when they’re supposed to be able to let off steam.

Every month, Roberto Clemente holds active shooter drills. Every month, Hanania’s 28 students cram into a closet-size bathroom — boys in the toilet stall, girls crowded around the urinal. The bathroom door has no lock. It swings open from the outside. The door has no handle on the inside. The students have no way to prevent someone from bursting in. An elevator opens directly into the classroom. No doors or hallways prevent an unwanted visitor from entering.

Hanania has taught in the same classroom for 20 years. She didn’t realize how much the school’s open floor design affected her students until her class was forced to evacuate after the Paterson Armory across the street burned down. The class spent months in a regular classroom at a nearby school.

“We were more productive,” she said. “It’s hard to explain. It’s just that feeling of, you’re contained. I try to imagine what their growth would be if we had not even optimal conditions but just a little closer to normal.”

Over $500 million from the state over two decades

What sounds like a simple remedy for Roberto Clemente — adding walls to divide a large room into four smaller ones — is far more complicated.

If you took the large space where Hanania teaches and divided it into four separate classrooms, each one would need an exit into a currently nonexistent hallway. They would need modern ventilation systems.

Given the age of the building, asbestos and lead paint could be hiding behind the plaster and in the ceiling, which would further complicate renovations.

And Paterson would have to find somewhere else for the school’s 270 students to learn while the building was being renovated — a tall order in a district where few schools have vacant space.

The other huge hurdle? Money. School renovation or new construction can cost tens of millions, even hundreds of millions of dollars when factoring in land acquisition — money Paterson doesn’t have.

The district’s 2022-23 operating budget was about $590 million. About $27 million — less than 5% of the budget — was dedicated to school maintenance and construction for the district's more than 40 school buildings.

That’s about $613,000 per Paterson school, a pittance compared with what’s needed to fund the myriad repairs that officials have identified across the district. That's roughly what it cost to replace two boilers, at Eastside and School 11. It's nowhere near enough to build a new school.

This school year, Paterson secured unprecedented help from the federal government, which typically does not fund school infrastructure, with two rounds of stimulus aid for facilities totaling $48 million. That money, along with a rare $4 million from the state to make emergency repairs, brought Paterson about $80 million for facilities in total out of an $800 million budget — welcome gifts the district doesn't expect to receive again.

While a wealthy district with a strong property tax base can afford to bond for school construction projects and pay back that borrowing, a city with a small property tax base such as Paterson doesn’t have that option.

So the state has been legally required to help. But even its efforts have been inadequate for the task. Through a series of momentous state Supreme Court cases and decisions collectively called Abbott v. Burke, the state must manage and pay the full cost of projects to repair or replace aging buildings in 31 of New Jersey’s poorest urban districts, including Paterson.

The Schools Development Authority and the previous Schools Construction Corp., the construction agencies formed to carry out the mandate, spent more than $516 million over two decades on Paterson school projects, the second-most for any district in the state, behind Newark.

With SDA resources, Paterson has renovated two older school buildings, built an addition and opened seven new schools — including International High School; P-Tech, with its planetarium dome; and Dr. Hani Awadallah School, which resembles a set of townhouses. And the state has paid for dozens of other projects: fixing boilers, doors, windows, ventilators, roofing and more.

But the number of renovations needed to improve the learning environment for Paterson students — and ensure their successful academic performance — remains staggering.

In an ideal world, Paterson should replace 12 aging schools, make major renovations to 19 other schools, and make smaller repairs at 11 schools, according to the district’s long range facilities plan, an inventory of buildings and the improvements they require.

“We really rejoiced when the Abbott decision came down, but then we were soon disappointed,” said Rosie Grant, executive director of the Paterson Education Fund, a nonprofit group that advocates for district improvements. “It took a lot of advocacy, parents going to SDA meetings, wearing hard hats and vests to be noticed, to advocate for facilities in Paterson. And while we did get some new schools, there is still so much need.”

An additional hurdle is the fact that the SDA’s first priority is not to repair old school buildings. Its primary focus is providing more space in New Jersey’s overcrowded urban schools. Combined, 21 SDA districts have a deficit of nearly 17,600 seats for existing students. Elizabeth is the most crowded, lacking space for more than 7,500 students. Paterson has the second-largest deficit, lacking space for 1,700.

Passing score: NJ high school graduation test will now allow lower score to pass

For subscribers: This is why Paterson can't afford $1.14M in overtime costs for city employees

In the meantime, Paterson relies on portable trailers or packs more students than recommended into classrooms. Paterson is planning to shift to a middle school model, moving middle school students into the same buildings to free up space in elementary schools across the district, said Neil Mapp, chief officer of facilities and custodial services.

So as the SDA scrambles to create space statewide for children to learn, renovating older school buildings takes a back seat, though three current projects in Camden and Salem deal with age issues.

The lack of available land for new schools is another concern, the agency says.

“Site acquisition is very costly and time consuming,” said Edythe Maier, an agency spokesperson. “We are first working through the high-priority projects that can be advanced soonest due to already available land.”

Borrowing billions to build

When it was launched, the SDA was the most expensive public works initiative in state history. It is primarily funded by debt. New Jersey received permission from the Legislature to sell bonds that brought in almost $9 billion to pay for new schools in the 31 SDA districts covered under the Abbott decisions, and almost $4 billion to pay for at least 40% of repairs or construction in other public districts, known as regular operating districts.

This borrowing costs taxpayers $1 billion a year to pay back.

That seems like a lot of zeroes, but if you divvy it out evenly (which isn’t how it works), it means each SDA district would have had $287 million to work with from bonds since the program began, or $12 million a year.

In Paterson alone, School 16 cost $57 million to build. International High School cost $53 million. Dr. Hani Awadallah School cost $53 million.

It’s been a decade and a half since New Jersey approved new bonds to fund the SDA, and the money is nearly used up. The construction agency has $650 million left to bond, according to April budget documents.

In the state’s past two budgets, Gov. Phil Murphy shifted $1.85 billion to school construction and repairs in the 31 poorest urban schools to push off another round of bonding.

Those recent infusions were budgeted to eventually build about two dozen schools the SDA prioritized in its strategic plan, which ranks districts that should get new schools based on how overcrowded their buildings are and whether land is available.

Paterson is on the list for an addition or renovation to make room for 1,000 students, planned on the site of the former Paterson Catholic High School, that will cost an estimated $160 million. But even then, the district would still be short 700 seats — without having addressed the crumbling ceilings, wall-less classrooms and other major problems in many of its existing schools.

The SDA is currently working with about $2.8 billion, when taking what remains of its previous bonding capacity and the funds in Murphy’s budgets, said Manny Da Silva, the agency’s CEO. But that money is already allotted to projects in its capital plan.

The projects that actually have funding would provide 11,700 seats statewide. That would still leave the SDA with 11,600 more seats to add before it could pivot to address crumbling, old infrastructure. Ideally, the agency could replace aging buildings with bigger, newer structures and fix the overcrowding and age problems at the same time, Maier said.

There are other uncertainties in the mix.

The Legislature is in talks to revise how the SDA operates, for the first time potentially allowing charter and renaissance schools to compete for the limited funding. Proponents say the agency needs to change how it operates after a series of scandals involving mismanagement and patronage. The agency said fixes made after a wave of bad publicity have led to a more efficient operation.

Planning to raze a school — for 60 years

Paterson has been trying to demolish School 3 since at least 1960.

That’s the year a report by Columbia University noted that the “entire building contains asbestos in wall and ceiling surfaces” and that it “can not be cost effectively renovated.” The report concluded that the school should be “taken off-line … due to age, condition, site constraints and other major limiting factors.”

What makes School 3 beautiful is also the root of a host of problems: its age. Above the front entrance, a second-floor stone balcony juts out under an ornate arch flanked by four columns. The words “Anno Domini MDCCCXCIX” are carved into the façade: in the year of the Lord 1899, the year the K-8 school was built.

In 2008, Gov. Jon Corzine signed legislation providing another $2.9 billion in bonding for the poor urban districts. School 3 was on the list of schools to be replaced. It would have cost an estimated $80 million to build a new school, a project that could have started in the spring of 2011.

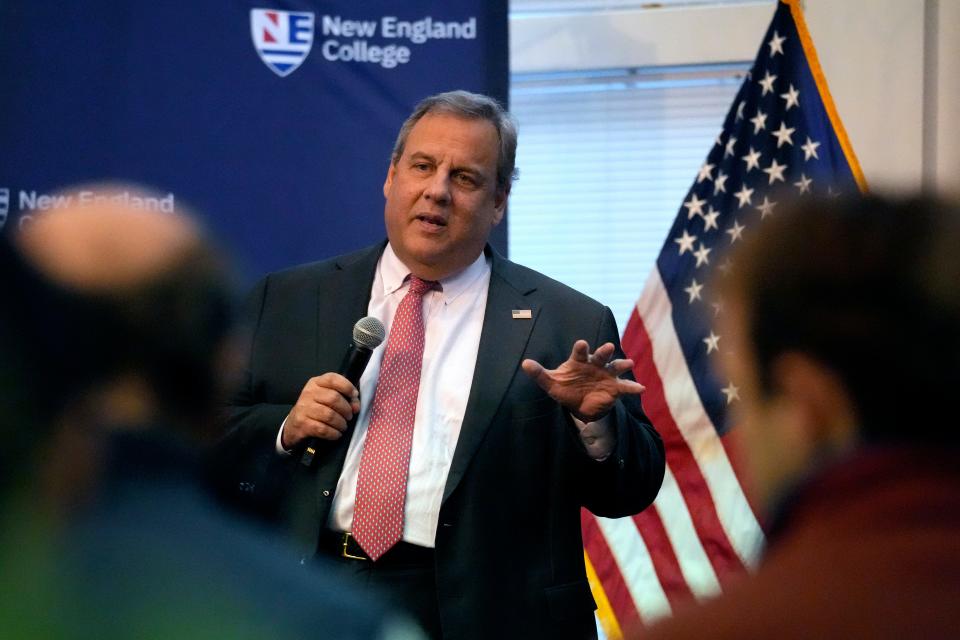

Two years later, a new governor was sworn in. Republican Chris Christie halted progress on schools in the SDA pipeline, calling for a review of about 100 projects that included School 3 and three other Paterson schools.

In 2011, after Christie pared down staff, reorganized the agency and shuffled the list of approved projects, School 3 didn’t make the cut because a new site was not available.

The Republican administration criticized the agency for waste and mismanagement it said had occurred under previous Democratic governors.

"The way these decisions were made before, candidly, was whatever the governor ordered, to have a school built, that's the way it worked," Christie said at the time. "There was no sense of objective prioritization to make these decisions."

More than a decade later, another generation of students and their teachers at School 3 continue to suffer.

Sandra Auletta said she has developed asthma in the 14 years she’s been an elementary school teacher there. She attributes it to the black, withered, rice-like mouse droppings she finds on her desk most days. She scrubs them off with Clorox wipes.

Auletta is afraid to touch the HVAC unit in her classroom. When the unit was on, she found it hard to breathe, and said she developed bronchitis and sinus infections monthly. Now she keeps the unit off and the windows open.

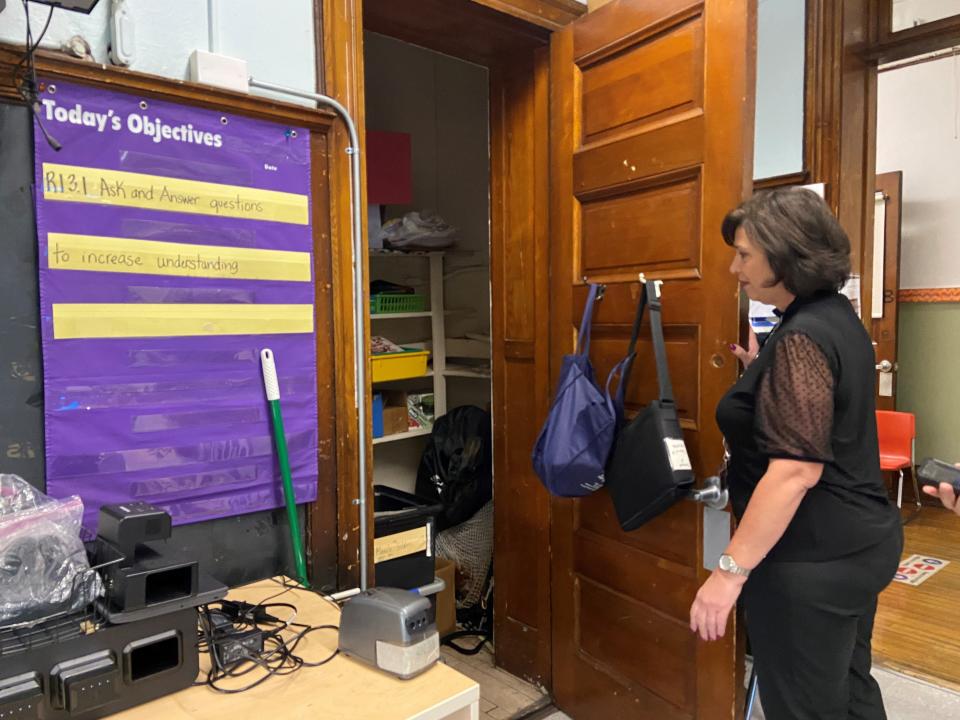

The closet in her third grade English classroom has ceiling tiles stained with what appears to be black mold.

“The building is so old and the pipes are so old,” Auletta said. “There’s a slop sink upstairs, and it just drains whenever somebody goes up there and uses it, so everything in there, my books, everything, is destroyed.”

A decade’s worth of emails to maintenance staff haven’t fixed the problem.

“On Friday the third floor bathroom leaked into my closet.”

“Please have my closet cleaned out. There are mice droppings, cockroaches, and fecal matter (which has fallen from the upstairs bathroom) in the closet.”

“Water is still leaking from the third floor bathroom, causing mold issues in my closet. The ceiling was removed as well as the asbestos, however the ceiling was never repaired after removal,” she said in an email from 2017.

Her frustration begins before she walks into the building. Auletta leaves her home in Verona at 6:45 a.m. — an hour earlier than she would like — to find street parking within walking distance of the school. What should be an easy 15-minute commute turns into a stress-filled search for an empty spot, as she circles city blocks.

The staff members at School 3 muddle through however they can. Children learn in two trailers so well-kept you wouldn’t know you were in a temporary structure. But on the outside, the rectangular boxes have broken paneling that covers the space between the elevated trailers and the ground. Auletta has seen people sneak in beneath the trailers, looking for a sheltered space to sleep.

Nine grades, spread throughout School 3’s three floors, share a single girls’ and boys’ bathroom. The “gym” is a classroom with low ceilings and tables folded against the wall. The room also doubles as a cafeteria.

Internet access is spotty. Teachers say they are sicker when school is in session. One teacher, Mayra Velasquez, said dangerously slanted stairs caused her to fall, fracturing her pinkie and injuring her Achilles.

“You almost become like a battered wife,” Auletta said. “You’re just used to getting abused. That’s how we kind of are. We’re just used to it.”

The epic tale of a leaking roof

The SDA is designed to tackle long-term problems, and districts must rely on operating and maintenance budgets to patch holes until they can get help. That can become more expensive in the long run.

“Most of the time, it takes the state three to four years to actually get to the emergency and actually do something,” said Steve Morlino, the former head of maintenance for both the Paterson and Newark school districts. “They tell you to stabilize it in between, and you do whatever you’ve got to do to stabilize it."

In Paterson, School 5’s roof had been leaking since the early 2000s. It festered, costs to contain the problem grew, and climate change ended up complicating matters.

School 5 Principal Jorge Ventura gestured at chalky efflorescence crusting over some clay-colored bricks in a stairwell, left behind by water seeping in through the roof. “I used to call them the ‘internal falls,’ or the ‘inner falls,’” he said of the leaks.

“In the beginning I thought it was soothing, like a therapeutic thing,” he joked, “but then after a while it was upsetting because the water was going from the ceiling all the way to the floor, and it created a slippery surface for kids. We had to shut the stairwell down.”

After nearly a decade of chronic water infiltration that loosened the terra cotta on the outside of the art-deco-style school, built in 1939, the SDA granted Paterson “emergent project” funding in 2010 to fix the roof and outside masonry.

Emergent project funding is designed to address issues that, “if not corrected on an expedited basis, would render a building or facility so potentially injurious or hazardous that it causes an imminent peril to the health and safety of students or staff,” according to the SDA’s website.

Paterson was supposed to be able to handle the roof and masonry repairs using less than $1 million in SDA funds. But once a district consultant evaluated the roof and recommended a complete replacement, the SDA took over the project management in 2015.

Six years passed before repairs began in June 2021.

The SDA said that before then “significant work occurred,” such as studies, design analyses, tests to see how well materials hold up under weather conditions, a historical reconstruction review of the terra cotta façade, a structural design of HVAC rooftop support structures, and bidding for the construction work.

Construction crews fixed the parapet wall around the roof's edge, ripping out cast stone, installing 2 feet of brick, and replacing the cap with a layer of aluminum flashing to prevent water infiltration. They installed roof structural supports to bolster a new HVAC system for the auditorium and gym. They laid out the membrane. All that remained was to slide some foam insulation underneath, said Da Silva, the head of the SDA. But the material was delayed due to COVID-related supply chain issues.

Then, in October 2021, a nor’easter struck, pummeling Paterson with 4 inches of rain that seeped down through the still unfinished roof, flooding 16 classrooms on the second and third floors.

Nearly 300 students — about 40% of the school — went remote until February, while fifth graders moved to a newly-built SDA school a 15-minute walk away, Ventura said.

“We had plastic draped over the edge” of the roof, Da Silva said. “It was nailed down. That plastic ripped. And that's how water got into that building, at least on that specific occasion.

Lawsuit: Paterson educator claims he was discriminated against — because he's white

Laurie Newell's salary: This is what Paterson's new superintendent of schools will be paid

“I could blame the contractor,” Da Silva said. “Could he have done a better job? We can always do a better job. We patched it, we sealed it and I think we had other storms right after that, and we didn't have the same issue.”

Before the nor’easter, the Paterson school district spent $336,000 to replace seats, flooring and rugs in its performing arts space. The theater is beautiful, reminiscent of the foyer of Radio City Music Hall, with long maroon-and-gold curtains framing ornate columns.

But last September, large plastic tarps remained draped over the newly installed maroon theater seats. The new blue carpeting was stained yellow from water that had leaked in from the roof.

The ornate columns are crumbling. The bas-relief image of a man is partly eroded away. The ceiling is stained, with paint peeling. The beams look wet, almost soggy, creating an unintended stucco texture.

“I do know for a fact that the auditorium was damaged before we got there,” Da Silva said. “The stair towers were damaged before we got there. Some of the classroom ceilings were damaged before we got there.”

The SDA finished repairing the roof in 2022 — seven years after it took over the project.

The SDA is putting together an asbestos abatement plan for the theater ceiling and walls. It’s unclear what the final cost will be, but the agency began work this spring and hopes to complete the renovations by summer.

The roof repair — originally estimated to cost $4 million — ballooned to $9.7 million. The district paid an additional $380,000 since 2015 on scaffolding at school entrances to protect children and teachers from falling debris, as well as other temporary fixes to prevent more water infiltration.

'You leave here exhausted'

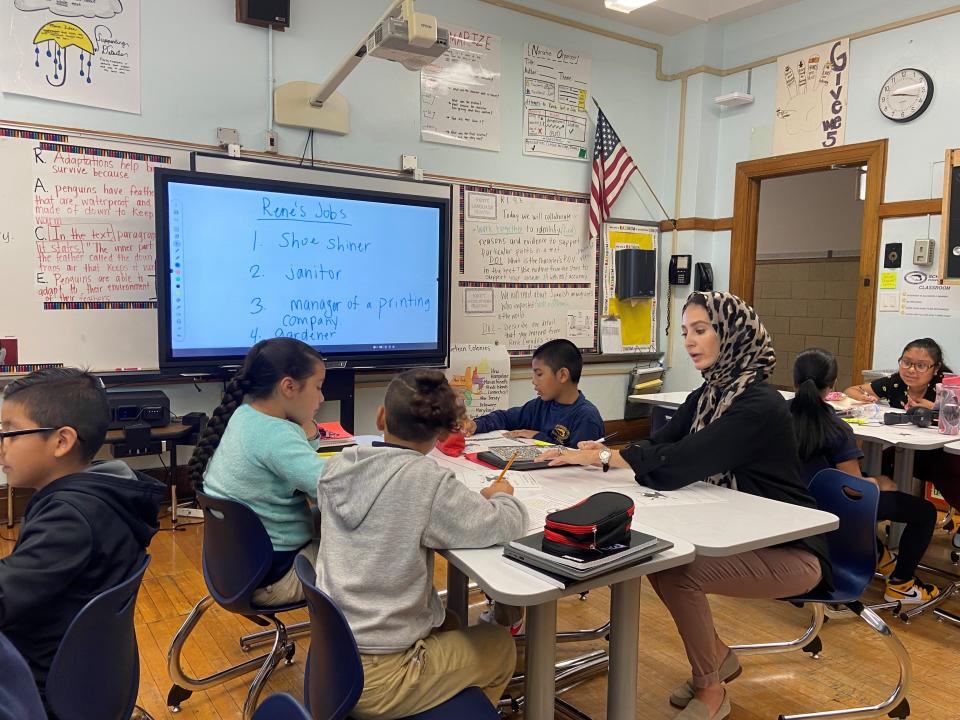

It has rained in Shereen Jaloudi’s classroom for eight of the 10 years she’s taught at School 5. The books she stored in lockers became soaked, and she had to throw them away. She remembers that one of her students, who used an inhaler, couldn’t take deep breaths.

“We can’t wait to get out for fresh air,” Jaloudi said. “You leave here exhausted. It takes a toll.”

On one particularly warm school day last fall, Jaloudi fanned her face and adjusted her leopard-print hijab. A few of the fourth grade girls in her English language arts and social studies class usually wear head scarfs — there’s a large Bangladeshi Muslim population in Paterson — but they took them off because of the heat. The room in the 84-year-old building doesn’t have working air conditioning. The HVAC unit expels lukewarm air.

Jaloudi’s classroom has two crowded electrical outlets, one at the front of the room to power her Promethean interactive display board, and a second behind her desk. There are too few outlets and too much to charge: a fan, an air purifier, her laptop, her students’ laptops, her co-teacher’s laptop.

Some teachers plug in surge protectors, frustrated because class gets interrupted when the power goes out and the circuit breaker needs to be flipped back on.

Jaloudi cracks open four of the six windows to circulate the air, but that brings in dust. A coat of sand-colored powder lines the outside window sill, blocked only by a screen peeling away from the frame. She’s not sure where the blowing powder comes from. It could be the crumbling mortar between the building’s exterior bricks. Or dust from a renovation of the neighboring Hinchliffe Stadium, where a parking garage, apartment building and restaurant have rapidly risen.

As the day wears on and the sun grows hotter, angling in through the windows, the students grow fatigued and distracted. They get up to fill their water bottles. They ask to take more bathroom breaks, so they can splash water on their faces. It’s hard for them to cool down after recess in the hot classroom. Jaloudi turns off the lights to help them relax.

“You’re drained by the end of the day, like you have nothing left,” Jaloudi said.

Patchwork maintenance won’t fix School 5. The building’s electrical and other systems were designed long before the hotter days and stronger storms fomented by climate change, long before the need for enhanced electrical capacity to power the technology that comes with online curriculums.

It was on a drizzly April morning in 1939 that city officials and 1,000 students celebrated the first cornerstone placed on the foundation of School 5. The Public Works Administration, the federal construction agency created under the New Deal, hailed the new school.

“Your children will have the advantage of healthier conditions, brighter classrooms and sufficient air — a striking contrast to the school houses that many of us knew in our youth. Such a fine structure should last for many years to come.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Paterson NJ public schools are falling apart despite $500M from state