Unspoken for 2 centuries: Bringing the indigenous Timucuan language back to life

A linguist and a historian have been working to bring back to life the Timucua language, which they say has likely not been spoken in more than 200 years.

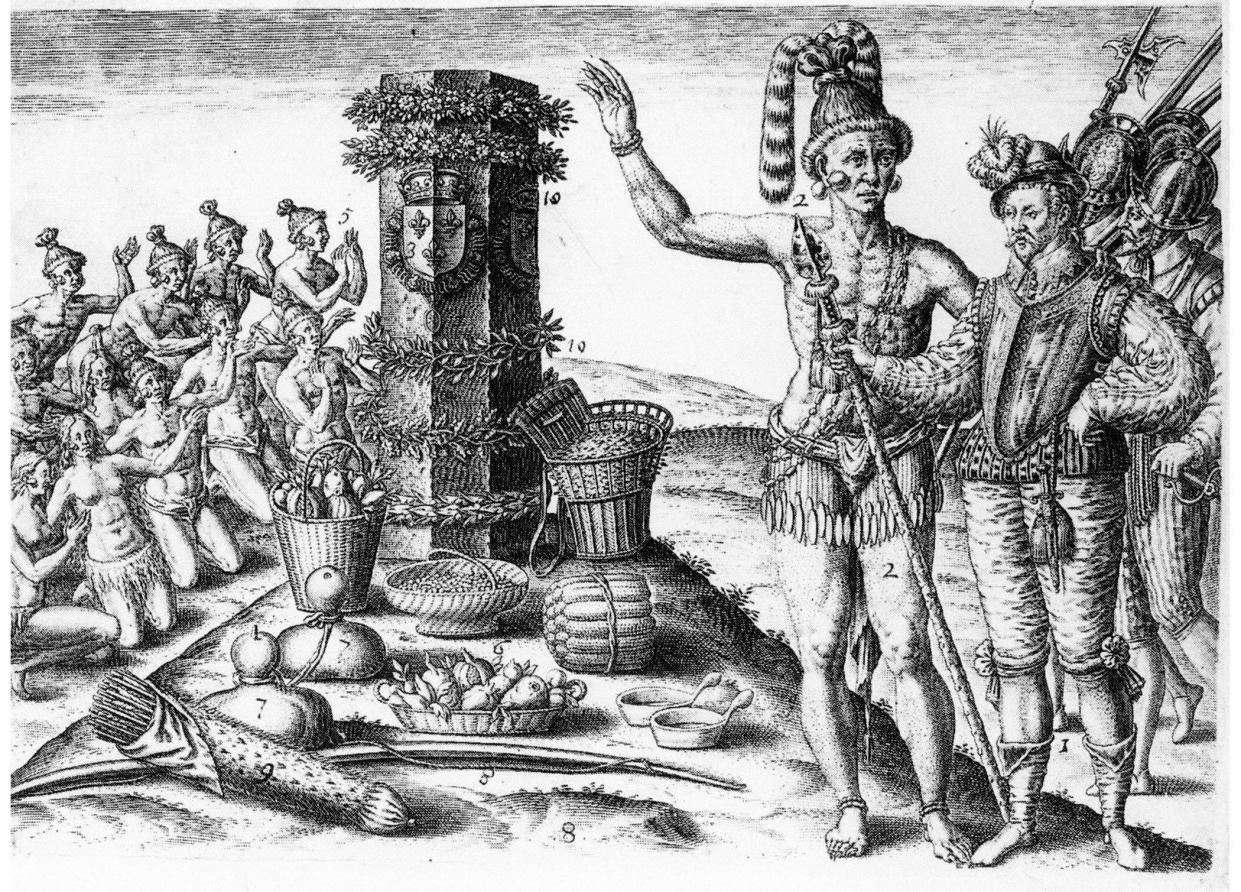

Unrelated to any other known language, Timucua, which was cataloged in Spanish archives, was the first indigenous language to be put into writing in what's now the United States.

It was once spoken by the indigenous people who lived in Northeast Florida and Southeast Georgia, in kingdoms that spread from the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

About 25 years ago, University of Florida linguist George Aaron Broadwell began building an online Timucua dictionary, with the help of other academics, generations of UF students and computer programs that look for patterns in the language.

It's now up to 147,000 words, most of them found in Spanish documents, many of them religious in nature and originally translated from Spanish into Timucua.

The main translators, Broadwell believes, were members of the coastal-dwelling people found in what's now Jacksonville, and other Timucua across the peninsula — not the Spanish missionaries who were long given credit for the work.

Letters from the past

There are also two surviving 17th-century letters of protest written by Timucua leaders to Spanish authorities, fascinating letters in which the Natives' voices ring through the centuries.

One was written in the Timucua language in 1651, and it petitions the Spanish authorities to improve the working conditions of the Timucua who labor on a Spanish farm.

It reads, in part: "In this village of Asile, now there are hardly any people. And when the people work, they repeatedly work without clothes or mercy. And so the laborers work for you and struggle and suffer torments and are exhausted for no purpose. And they are tormented and they don’t want to work. And I too don’t want them to end up exhausted for nothing."

Broadwell translated the letters with Alejandra Dubcovsky, a historian at the University of California, Riverside who specializes in Spanish Florida. She's worked with Broadwell since 2012 and has learned Timucua as a way, she says, to better understand the people who spoke it.

"It shows how they’re confronting the incredible repression of colonial oppression in their writing," Dubcovsky said about the 1651 letter. "It shows the level of sophistication and intellectual engagement that we don’t have in these other sources.”

For Broadwell, who specializes in the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Southeast, learning the language is a way of honoring those who lived in the area.

"I think we owe the original inhabitants of the land the respect of trying to understand their lives and their history," he said. "To read the language of Native people about their own treatment and political situation is really important and powerful."

An indigenous history: UNF profs to tell the story of Northeast Florida's Mocama people

It has been a herculean effort to document the language, since no one has spoken in hundreds of years. Luckily, the Spanish who settled the area in the 1560s after driving out French colonists at Fort Caroline were meticulous record keepers.

They also were intent on converting the Timucua to Catholicism, so there are numerous religious works showing Spanish on one side, Timucua on the other. Those were invaluable in recreating the language, as were the two letters found in the archives that were actually written in Timucua.

Want to read and speak Timucua?

Through his translation work, Broadwell said he understands that the language has a whole system of marking respect for other people; verbs change and there are special suffixes on nouns

"It’s a subtle and kind of beautiful thing," he said.

The translators also found clues in the language to how the Timucua looked at gender. It's known that they had a third gender role that was not exclusively male or female.

“Timucua only has a single word, spouse, and no word for husband or wife, or for he or she," Broadwell said. "A lot of things that are very gendered in the Spanish version turn out to be gender-neutral in the Timucua version.”

Mark Woods: Among the things I didn't learn in school — the value of 'revisionist history'

Dubcovsky praised the decades of work done by her colleague Broadwell.

"What he has done is truly extraordinary," she said. "He has created this database of every single Timucua word, put in programs to try to figure it out. He has completely pieced the language apart and pieced it back together, so we can figure out how the language works."

What that means is monumental, she said. "He has given us the tools to be able to read a language that is not spoken anymore.”

The resources are there: Along with the online dictionary, there is also an online Timucuan language resource guide at hebuano.wordpress.com. It has lessons, a vocabulary (on numbers, animals, colors, etc.) and tips on how to read Timucua.

For decades, the conventional wisdom is that the Timucua died out, victims of slavery, disease, warfare and destruction. Now, though, scholars believe that their descendants are alive today, having escaped the threats they faced by joining other indigenous nations.

Today, for example, both the Muscogee Creek Nation of Oklahoma and the Seminole Nation in Florida claim the Timucua as ancestors.

Broadwell thinks that perhaps some people will want to gain at least a passing familiarity with a language spoken widely in the area, long before and after Europeans arrived.

“The language hasn’t been spoken in about 200 years," Broadwell said. "But we do think there are descendants of the Timucua who are interested in learning some phrases, and a lot of people might be interested in learning to read Timucua."

It's rewarding work, he said. “When you learn another language, you get access into the way other people’s minds work. It’s given me a lot of compassion and insight into the first people of this region.”

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: The language spoken by the Timucua of Florida still lives on