Unsung Detroit heroes: 2 Martin Luther King Jr. marches possible

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

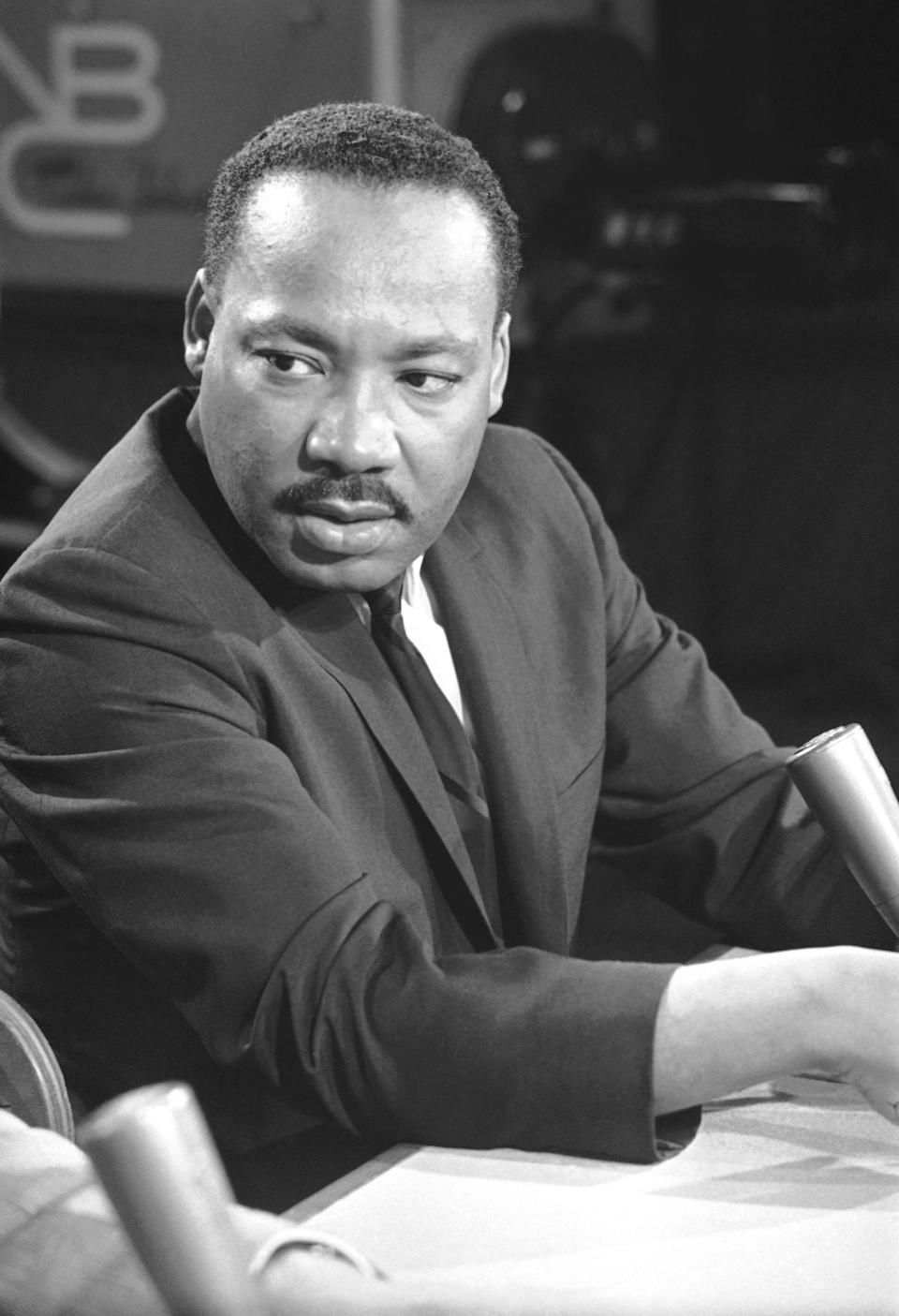

Nearly 60 years ago, on Aug. 28, 1963, the largest civil rights demonstration in U.S. history was held in Washington, D.C. At least 250,000 people participated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.Although there were a number of speakers and performers that day, Martin Luther King Jr. was the final speaker. And his speech — “I Have A Dream” — still is considered one of the greatest orations in history.

But what if I told you that the plans for that march began decades before it took place, and that the “I Have a Dream” speech was given months before the world heard it at the Lincoln Memorial?

And what if I also told you that Detroit is central to this story?

Let’s go back, not to 1963 …

But to 1940.

As the U.S. was emerging from the Great Depression, and Europe was already at war, the defense industry was increasing production and putting thousands of men to work. U.S. factories were gaining lucrative government contracts to manufacture guns, ammunition, airplanes and other military equipment.Yet, African Americans were being denied the opportunity to work in these well-paying jobs.

Black leaders began to meet with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss the issue of job discrimination in the defense industry.

After significant correspondence between African American leaders and activists and the Roosevelt administration, three of those leaders — Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP; Thomas Arnold Hill, director of industrial relations for the National Urban League, and A. Philip Randolph, union organizer and leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters — met with Roosevelt and demanded racial integration and equality in the Armed Forces and desegregation in the defense industries.

The White House’s response was the continued refusal to integrate the Armed Forces, or open the government’s defense training programs to Black people because the factories would not hire them after their training.

In January 1941, Randolph declared a March On Washington would take place on July 1.

This march would be, according to Randolph, a “nonviolent demonstration of Negro mass power.”The march was supported by Black newspapers, and committees were organized in cities across the nation with a plan to bring 100,000 African Americans to Washington D.C. to engage in nonviolent protest and civil disobedience to bring pressure and attention to government-backed discrimination against Black workers.

Roosevelt, worried that such a march could hurt him politically, agreed to the forming of the Fair Employment Practices Committee and issued Executive Order 8802, which barred discrimination in defense industries, federal agencies and work training programs.

This was the first time since the Civil War that a U.S. president issued an executive order guaranteeing rights for Black people.So, Randolph called off the march.

But it wasn't over

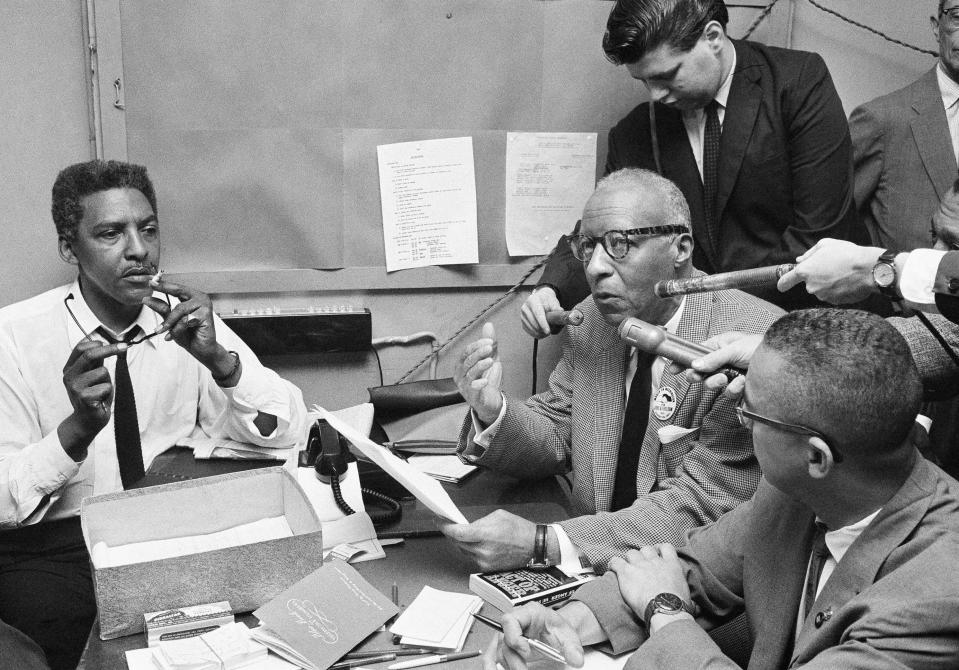

However, Bayard Rustin, an assistant organizer of the march, disagreed with Randolph and believed the march should not have been canceled. As the years passed, Randolph would come to agree with him.

After the successful Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1954 and the Montgomery Bus Boycotts of 1955-1956, Randolph and Rustin were convinced that there was a need for another major march on Washington.

In 1957, they partnered with King's newly founded Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the NAACP for the Prayer Pilgrimage For Freedom March in Washington D.C. Some 25,000 people participated.King, the keynote speaker, gave a speech named “Give Us The Ballot,” urging federal legislation for Black voting rights in the South.Still, compared to the plans for 100,000 Black people to march on Washington in 1941, Rustin and Randolph believed something more needed to happen.

In 1961, during the period of sit-ins and freedom rides, Randolph and Rustin began planning another massive march on Washington for October 1963, focusing on economic inequality rather than voting rights, desegregation of schools and integrated public accommodations.

Randolph and Rustin believed that the civil rights gains would not be enough if Black people were still blocked from access to jobs, bank loans and other avenues of attaining financial equality.

But then came Birmingham.

Birmingham changed everything

The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a Baptist pastor in Birmingham, Alabama, and founder of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, was repeatedly jailed for his involvement in civil rights protests.After his home and church had been bombed, he invited King and the SCLC to Birmingham to lead the movement against Jim Crow.

Along with the supporters of racial discrimination and segregation in Birmingham was the Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor.Connor would unleash cattle prods, police officers with billy clubs, police dogs and high-powered water hoses on Black men, women and children who marched in downtown Birmingham.

The televised attacks against nonviolent civil rights protesters prompted Randolph and Rustin to begin talks with the NAACP, the SCLC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) for a civil rights march in Washington, D.C.And this march would focus on civil rights and economics. It would be named the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

A coalition of leaders

Just as Randolph and Rustin were moved by seeing what was happening in Birmingham, so were many other Black leaders and organizations.

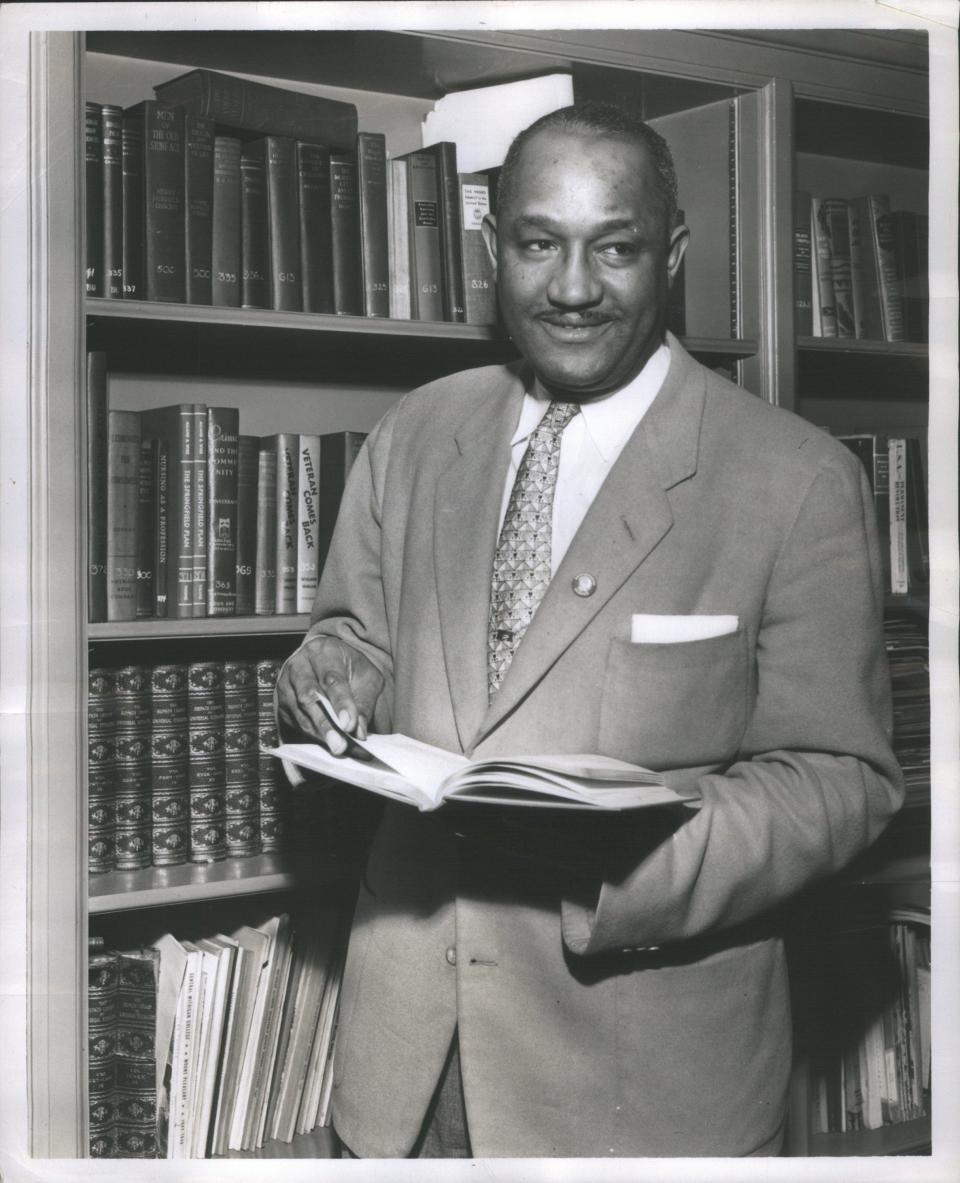

After reading King’s “Letter From A Birmingham Jail,” the Rev. C.L. Franklin, pastor of New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit and father of the "Queen of Soul" Aretha Franklin, began planning a way to support King and the Birmingham movement.Franklin held a meeting at the Detroit Urban League office to discuss what should be done in Detroit to support King in Birmingham.Others at the meeting included Francis Kornegay, president of the Detroit Urban League; James Del Rio, an attorney and civil rights activist who would later become a judge, and Benjamin McFall, an owner of a number of Detroit funeral homes.

Two days after that meeting, the Rev. Albert Cleage Jr. (later, Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman) of Central United Church of Christ (later, the Shrine of the Black Madonna), was one of the leaders of a meeting at the Lucy Thurman Branch of the YWCA — the Black YWCA.

This group planned to raise funds for the SCLC and the Birmingham Campaign, but they also discussed whether they should join with the Rev. Franklin’s initiative.

Who else was there?

John Conyers, then-labor and civil rights attorney, soon to be a congressman; Nathan Conyers, then-civil rights and labor attorney, later a businessman and owner of a large auto dealership; Damon Keith, then-civil rights and labor attorney, later a federal judge; George Crockett, the eldest of the lawyers there, then a civil rights and progressive activist attorney, later a judge, state representative and U.S. congressman; the Rev. Nicholas Hood, pastor of Plymouth Congregational United Church of Christ, a founding member of King’s SCLC, and soon to be the second African American elected to the Detroit City Council; Horace Sheffield, co-founder of the Trade Union Leadership Council, a major Black labor organization, and Buddy Battle, co-founder of the Trade Union Leadership Council.

On May 17, the anniversary of the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage to Freedom and the anniversary of the 1954 Brown decision, a mass meeting was held at New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit. And the Detroit Council of Human Rights was formed.

Franklin was the president; Cleage, McFall and Del Rio were executive board members.

The group planned a march, to be led by King, for June 2 or 3.

It was originally planned as an all-Black march, like the 1941 Randolph-led march was supposed to be. The funds raised would go to King and the SCLC, mainly to deal with the Birmingham Campaign. Anything over $100,000 would go to the DCHR so that the group could address civil rights issues in Detroit.

A bumpy road

Almost immediately, the DCHR was met with strong opposition from the attorneys, John and Nathan Conyers, as well as George Crockett and Damon Keith, the Baptist Ministerial Alliance and the Detroit Branch of the NAACP.

They objected to Franklin being the organizer of a civil rights march — neither the attorneys nor the NAACP saw him as a civil rights leader — and Cleage’s Black nationalist ideology and plans for an all-Black march.

Largely due to the Birmingham Movement, most of the civil rights fundraising and donations was going to the SCLC, and causing some tension between the NAACP and the SCLC. Some people in the Baptist clergy, as well as the Detroit community, felt that Franklin and Cleage did not act like proper men of the cloth.

The NAACP led the charge for Franklin to step down as the leader of the march. However, U.S. Rep. Charles Diggs Jr., the highest Black elected official in Detroit, supported Franklin. Also, Franklin’s New Bethel Baptist was the largest church in Detroit with 10,000 members.

And both King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, wrote letters in support of Franklin.

So Franklin stayed.

Marching forward

There would be compromises.

Tony Brown, a journalist with the Detroit Courier who years later would become the founding host of the show "Detroit Black Journal," was chosen by James Del Rio to be coordinator of the march, in much the same way that Randolph recruited Rustin to be the coordinator of the march on Washington.

With Brown as the organizer, the march would no longer be an all-Black march. White people of goodwill would be invited and UAW President Walter P. Reuther would become a co-chair of the march.

Other white leaders, including immediate past governor John Swainson, Gov. George Romney and Detroit Mayor Jerome Cavanaugh, also would help in the planning.

With those concessions, along with the public support of King, the Detroit Branch NAACP could no longer condemn the march. But the group still refused to endorse or participate in the march.

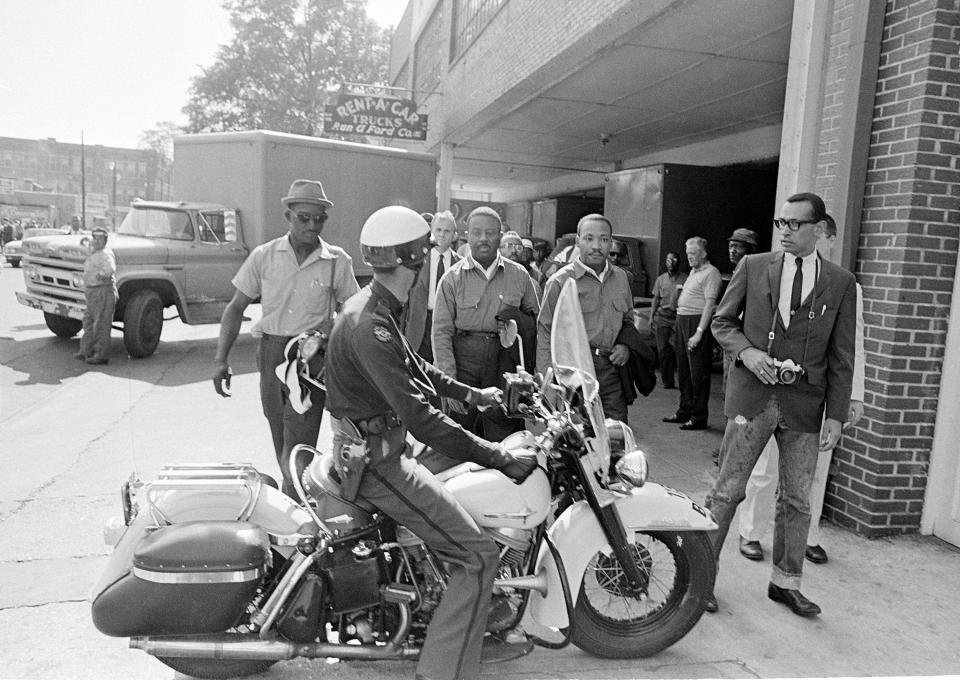

The Detroit Walk to Freedom took place on June 23, 1963, the 20th anniversary of the end of the 1943 Detroit race riot.

Just like the Washington March, the Detroit march had 1940s roots.

At least 125,000 people — some say 250,000 or more — marched from Woodward and Adelaide streets (one of the epicenters of the 1943 race riot) to Woodward and Jefferson. The marchers ended at Cobo Hall, and some of the march leaders delivered speeches at Cobo Arena.The high point was the 30-minute speech delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. that culminated in the “I Have A Dream” refrain that would become famous two months later at the march on Washington.

Dreaming in Detroit

He gave the “I Have A Dream” speech in Detroit before he did it in Washington D.C.But Detroit was not the first time he gave the speech either.Since 1960, King had been giving speeches about “the Negro and the American Dream.” In these speeches, King would often discuss how white racism was preventing Black people from obtaining the American Dream of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

In September 1962, a civil rights activist with SNCC, Prathia Hall, was praying at the site of a burned-down church in Albany, Georgia. She kept using the refrain “I have a dream.” King was there too.

In November 1962, King spoke at the Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, N.C., and he included the “I have a dream” refrain.

And the “I Have A Dream” speech was born.

The speech in North Carolina was 50 minutes long, delivered to a relatively small crowd.

The speech in Detroit was 30 minutes long, shorter than the North Carolina speech, but twice as long as the one delivered in Washington. And unlike the small group at Rocky Mount High School in North Carolina, there were thousands of people in Cobo Arena and even more outside listening on loudspeakers.

In the Detroit speech, before he began the “I Have A Dream” apogee, he delivered a talk about the work being done in the South, especially what was going on in Birmingham; the significance of nonviolence; the need to avoid “Black Supremacy," and the northern manifestations of Jim Crow that existed in Detroit — including school inequality, housing segregation and job discrimination.

And he ended with his dream.

Getting the word out

King and the SCLC had been in talks with Motown Records, and met with Berry Gordy Jr. at Cobo to finalize negotiations for recording and distributing the speeches in Detroit and the march on Washington. The proceeds of the record sales would go right back into the Civil Rights Movement.

Many people listened to the speeches over and over again, even memorizing them, because of Detroit’s own Motown Records.

And just as the March on Washington helped change the nation — President John F. Kennedy began pushing for a Civil Rights Bill — the Detroit Walk to Freedom would spark change in Detroit.

Franklin would organize a Northern Leadership Conference at Cobo Arena in October 1963, with Rep. Adam Clayton Powell as the keynote speaker. The Rev. Cleage would organize the Northern Grassroots Leadership Conference at King Solomon Baptist Church, where the keynote speaker was Malcolm X.

Civil rights groups and Black Power organizations in Detroit would all be able to lay claim on their participation in the Detroit Walk to Freedom.

Although the Detroit Branch of the NAACP did not participate in the 1963 March, they have, under the leadership of the Rev. Wendell Anthony, been chief organizers of the 30th anniversary, 40th anniversary, 50th anniversary and this year’s 60th anniversary march.

Reclaiming our heroes

And although people who remember both the March on Washington and the Detroit Walk to Freedom mainly recall King and his speeches, the March on Washington would not have happened without the many years of planning and work of Randolph and Rustin.

And the Detroit Walk to Freedom wouldn’t have happened without the short-lived partnership of Franklin and Cleage, and the nearly as short-lived Detroit Council for Human Rights.

So many know little to nothing about the Detroit March because of the falling-out between Franklin and Cleage and the dissolution of the DCHR. Although their names, as well as the march, are legendary in Detroit, both have been relatively unknown and unconnected to the larger Civil Rights Movement.

But unsung heroes are still heroes.

Jamon Jordan is the city of Detroit's Official Historian and the founder of the Black Scroll Network History & Tours. He teaches a class on Detroit history at the University of Michigan.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Anniversary of Martin Luther King 'I Have a Dream speech' in Detroit