Unsung heroes: Vietnam-era 'Swifties' are finally getting their due

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Well before Taylor Swift fans co-opted the term, there was another group of “Swifties” — Navy veterans who operated highly dangerous Swift Boat missions in Vietnam.

When someone talks about Swifties today, however, it’s unlikely they are referring to the Vietnam vets. Today’s Swifties obsess about Taylor Swift and know everything about her music and her life.

But for Swift Boat veterans, co-opting the name creates angst. Kate Zernike wrote a New York Times story about the original Swifties. When Navy vets talk about Swift Boats, she wrote, “They recall friends and crewmates killed, countless moments of sheer terror in their young lives, the pain of coming home to a country that offered less than a hero's welcome.”

Will Croll, a Vermont native who now lives in Portsmouth, understands those feelings. He enlisted in 1958 and went to Vanderbilt University under the Navy Enlisted Scientific Education Program. After graduation, he commissioned from Officer Candidate School, served one tour on a destroyer, then went to Vietnam for Swift Boat service. Croll was reluctant to go into detail, saying, “I left a lot of that behind.”

The men and their Swift Boats

Swift Boats were basically fast, light gun platforms, agile enough to patrol in shallow waters, but still powerful enough to serve as fearsome offensive weapons. Some 125 were built, and they fought in the U.S. Navy from 1965 to 1970, when they were transferred to the Vietnamese Navy.

The 50-foot aluminum craft had radar, and its two 475-horsepower diesel engines generated a maximum speed of more than 30 knots. Its narrow draft (less than 5 feet) allowed it to get close to shore and into smaller canals that larger patrol boats could not approach.

They were loaded for bear, with twin .50-caliber machine guns mounted over the pilot house forward. A unique over-and-under mount in the stern featured an 81 mm mortar with a .50-caliber machine gun piggybacked above it. In trigger-fire mode, the mortar could become a direct-fire weapon.

Each crew of six had an officer-in-charge (usually a lieutenant junior grade) and five enlisted sailors. Everyone was cross-trained on the various weapons and equipment.

Swift Boat duty was for volunteers only. Despite the stressful and always dangerous duty, Swift Boat sailors (some 3,600 of them) maintained unusually high morale and esprit de corps through the course of their five-year mission.

Of these members of the “Brown Water Navy,” some 400 were wounded. Fifty died.

Life serving aboard the Vietnam-era Swift Boats

In addition to supply interdiction and combat patrols, these boats also inserted Navy SEAL teams into enemy territory. Simply stated, Swift Boats conducted some of the most harrowing missions of the war. They faced the constant threat of naval mines, as well as rocket fire from an enemy bunkered on riverbanks as few as 30 feet away.

And, as former Swift Boat skipper John Scholl told the New York Times, "The bad guys shot at you on the way up the river, and they knew you had to come back down."

Firefights involving Swift Boats were not long, drawn-out engagements, simply because the boat was a very visible target to a dug-in and largely invisible enemy.

The best solution for survival was a massive return of fire combined with a high-speed departure. Though most cruising and patrolling was done at 8 to 10 knots, the boats could reach a top speed of 32 knots.

Other operational challenges

Jamestown resident Daniel Ustick, originally from Philadelphia, graduated from Bates College in 1963. He enlisted in the Navy and earned an OCS commission early in 1965. After a tour on a guided missile destroyer, he volunteered for Swift Boats and graduated from that training in May 1968.

“We responded not just to firefights along the river banks, but also to calls for fire support further inland,” Ustick told me. “In the stern, we had an 81 mm mortar mounted in an ‘over-and-under’ combination with a .50-caliber machine gun. We would set bow and stern anchors to give us some stability. Then we could fire mortar rounds –usually flares – to help units in contact with the enemy.”

Weather was also an issue, especially at the mouth of the Cua Viet River, up near the border with North Vietnam. While the Swift Boat base was sheltered in a calm spot upriver, getting to it could be a challenge in rough weather. During monsoon season, 15- to 20-foot waves crashed through a narrow, 200-foot-wide channel at the river mouth.

“Surfing” the 50-foot-long boat was often the only way to reach the safety of the base. (At least two boats were lost attempting this maneuver.)

Will Croll also lived through the Cua Viet surfing experience, since his crew’s tour was as a replacement boat.

“When a boat assigned to a unit went off-line for repairs or maintenance, my crew and I would fill that hole. I actually bounced up and down the entire Vietnam coast from Cua Viet to Phu Quoc Island.”

David Brown’s quest begins

I have written about veterans receiving their awards many years after the fact. Each such column has been about one person getting one set of overdue medals.

Today’s column is about some 60 veterans getting 60 sets of overdue medals.

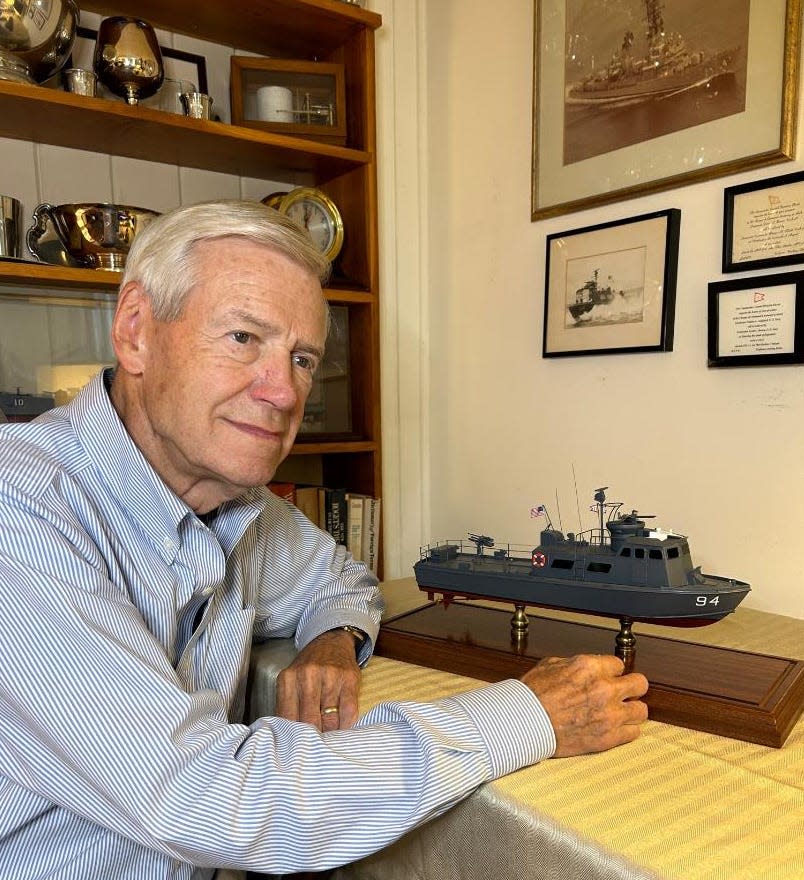

And one man — retired Navy Capt. David Brown of Middletown — is largely responsible for getting this error corrected.

“What Dave Brown has accomplished is amazing,” says Ustick.

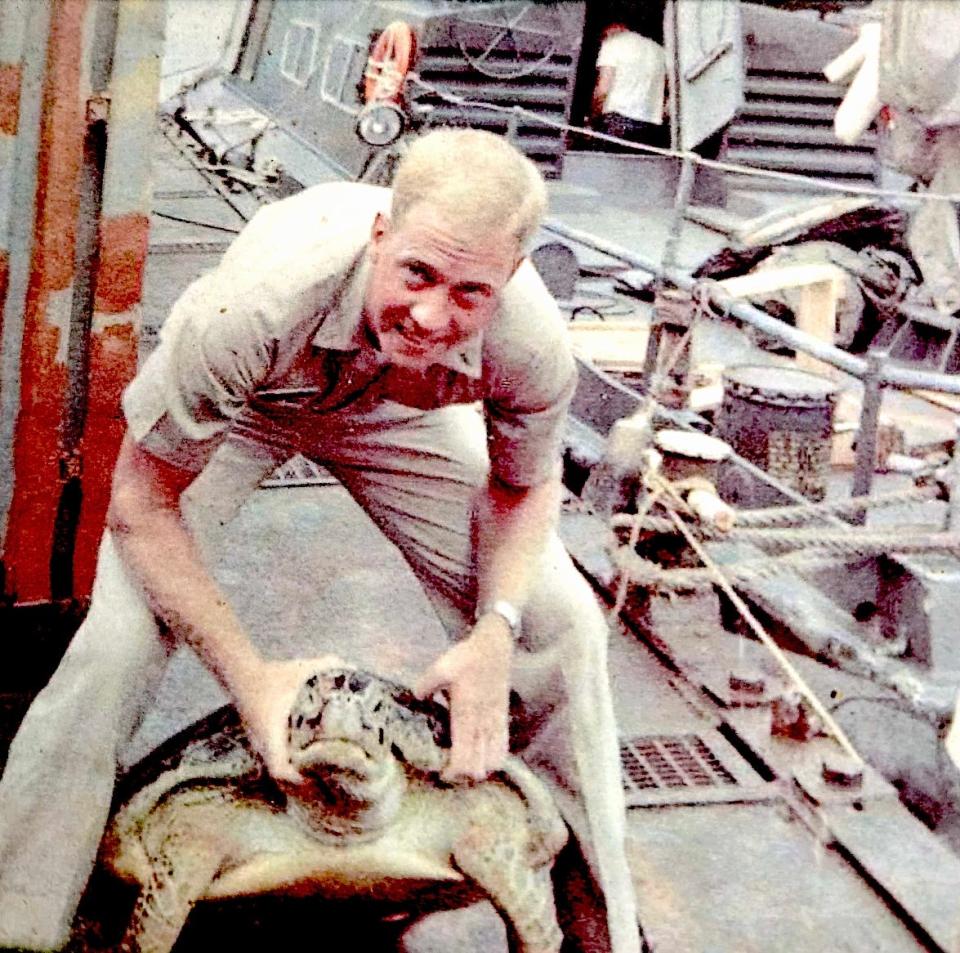

Brown, a 1962 Naval Academy grad, served aboard a destroyer and attended Naval Postgraduate School before undergoing Swift Boat training at Coronado, California. He headed for Vietnam in June 1967.

Brown commanded Coastal Division 11, a unit of Swift Boats based at An Thoi, adjacent to Cambodia. He was responsible for 30 six-man crews who, in rotation, operated 20 PCFs (Patrol Craft Fast, the Navy lingo for Swift Boats).

Administrative nightmare begins

By the end of his tour, Brown had assembled the necessary information to submit awards for more than 70 junior officers and sailors from his unit. “I worked nights and weekends at my next duty station finishing up this paperwork,” Brown told me. He submitted the recommendations and forgot about it.

Sadly, the entire packet of nominations disappeared within the Navy’s bureaucracy — but Brown did not know about it for many years.

He eventually crossed paths with a fellow Swift Boat officer from 1968, and only then did he learn that none of his men had received their awards.

This situation did not sit right with Brown, and it bothered him for years.

“After my retirement, I was going through a box of Navy papers,” Brown told me. “I found the files I had used to prepare the original submissions in 1968.”

They weren’t copies of the award recommendations, but they were the next best thing: drafts of the documents and the raw data used to submit them.

Brown was able to re-create 73 recommendations. But changing official military records can be an arduous and time-consuming process.

For eight years, Brown tried on his own to get the files moved through the approval process. While he waited, more of his aging shipmates passed away without ever receiving their medals.

In 2019, Brown turned to U.S. Sen. Jack Reed for help. Reed and his staff jumped on the case, and they worked with Brown to navigate the administrative process (which eventually required the secretary of the Navy's approval). Federal government help to locate the award recipients was also needed.

Reed acknowledges that lost paperwork and delays in receiving awards are not uncommon. “What is uncommon,” said Reed, “is Mr. Brown’s tireless efforts over the years to ensure his fellow sailors were appropriately recognized. I salute his hard work.”

Brown is harder on himself. “I’m not the hero here,” he said, pointing out that had he followed up back in 1968, none of this would have happened. “I spent years trying to fix my own failure. I should have made sure before I left Vietnam that all those award recommendations were properly processed.”

To date, 58 of the original 73 award recommendations have been approved, and about half have already been presented. Thirteen of these were Bronze Stars for Valor, our country’s fourth-highest award for heroism.

“These medals are a symbol of honor and a small but meaningful token of our profound thanks to these veterans and their families,” said Reed.

After his Swift Boat days, Brown completed a full Navy career, retiring as a captain. After retirement, he was appointed rear admiral in the U.S. Maritime Service and headed both the Great Lakes Maritime Academy and New York Maritime College.

With special thanks to Chip Unruh of Sen. Jack Reed’s staff, who did the heavy lifting for this column.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Vietnam era Swift Boat crewmen finally get recognition