A Dark, Untold Story About the March on Washington Has Just Been Revealed

In the summer of 1963, countless Americans were making arrangements for the March on Washington. They attended meetings where speakers urged audiences to travel to the Aug. 28 rally. They scoured bus schedules, and they made their way to train stations. They grabbed their cameras to document the big day.

Most of these people preparing for the march planned to travel to Washington to demand an end to legalized racial discrimination. But some of them were police who secretly watched those who protested.

It’s common knowledge that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI blanketed Martin Luther King Jr. with surveillance. Historians have also long known that more than 100 employees of the bureau’s Washington field office were assigned to observe the march. But through my research in municipal records from Chicago, Birmingham, and New York City, I have learned another uncomfortable truth: Local police officers in secretive intelligence units across the country also spied on the activists who attended the March on Washington. Some police without jurisdiction in the nation’s capital even traveled hundreds of miles to monitor the rally in person. Why?

This question is far from academic. In our current moment, on the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington and as local law enforcement spies on a new generation of activists—from Black Lives Matter organizers in Colorado to those calling for defunding police in Los Angeles to the Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta—it’s well worth considering the history of the police who weaponized surveillance against movements for racial justice.

The standard account of law enforcement and the March on Washington, the one told by media in 1963 and repeated by historians, goes something like this. Some 1,900 of Washington’s police—nearly two-thirds of the city’s entire force—patrolled the march. They were assisted by an assortment of 400 additional military police, reservists, and park police, for a total of 2,300 officers. Law enforcement at the march far outnumbered the 1,800 police who had guarded John Kennedy’s presidential inauguration in January 1961—a much larger event that drew an estimated 1 million people. In anticipation of mass violence at the march, Washington police banned the sale of alcohol for more than 24 hours and transferred 350 individuals incarcerated in the city’s jail to other facilities to free up space for mass arrests. To put it bluntly, white people in Washington were afraid of Black people coming to their city to demand their rights.

But there was also the Guardians Association, a group of Black off-duty officers primarily from the New York and Philadelphia police departments who traveled to Washington to serve as volunteer marshals. Organizers hailed the off-duty cohort as the march’s “own police to maintain order and internal security among the marchers.” They had good reason to believe that the Guardians would be more dedicated to protecting the crowd than most white police officers. Nearly 1,500 Guardians took up the call to serve at the march. Bedecked in gold armbands and white caps in honor of Gandhi, they regarded their duties not only as an assignment to keep the march safe and orderly, but as the opportunity of a lifetime, a chance to serve the movement and be a part of history. Several of them appeared on national television, standing just one row behind the podium as the day’s speakers addressed the crowd.

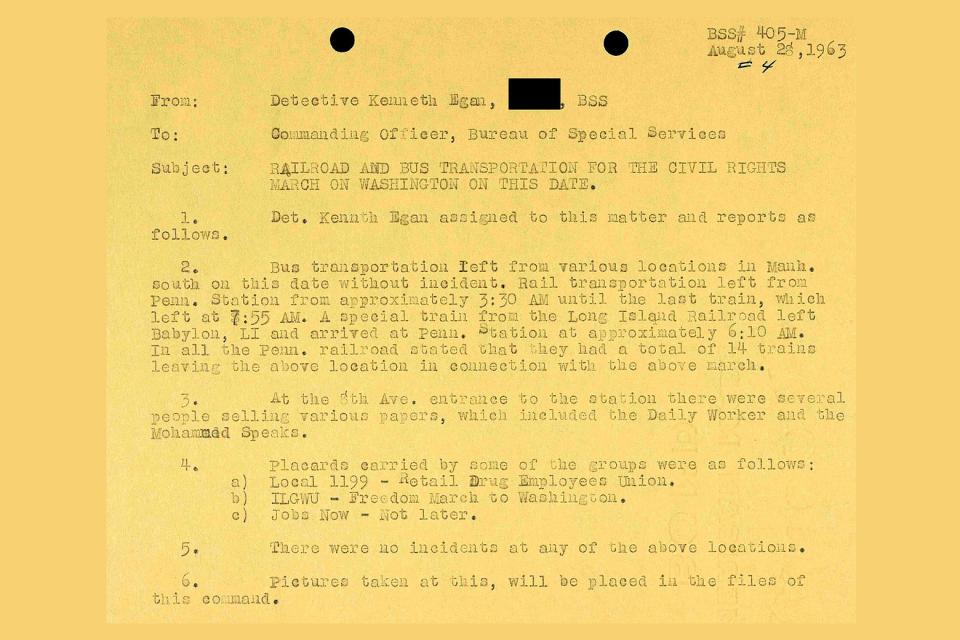

Yet these were just the police who openly watched the March on Washington. Back in New York, the NYPD’s intelligence unit, known as the Bureau of Special Services, or BOSS, quietly monitored the extensive logistical planning carried out by the march’s organizers headquartered in the city. In the days leading up to Aug. 28, BOSS compiled inventories of the more than 400 buses and 100 trains scheduled to travel from New York for the event. Intelligence officers tracked the plans of established civil rights organizations already under their watch. But they also took note of other groups arranging travel to the march: churches and unions, a local chapter of the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, and small businesses with less-than-subversive names like Whimpey’s Restaurant and Harlem Steak House.

BOSS officers at Penn Station and various departure points on the morning of Aug. 28 monitored thousands of marchers as they boarded trains and buses. They shared the information with Washington’s Metropolitan Police and made sure to photograph individuals on their way to the march, filing the images away in BOSS’s extensive dossiers. In Chicago, local intelligence detectives obtained lists of residents planning to attend the march, and they conducted surveillance at the city’s Grand Central Station to record the names of individuals leaving by train on Aug. 27 for the following day’s events in the nation’s capital.

One of the more disturbing responses to the March came from the all-white police department in Prince George’s County, Maryland, just outside Washington, where officers feared the march might spark disturbances beyond the District’s city limits. As a precautionary measure, police officials contracted the National Institute of Mental Health to train their department’s newly formed Civil Disturbance Unit in “mediating contemplated interracial conflict in the public streets.” Government psychologists quickly found their assignment more difficult than they had anticipated.

A majority of the officers in the trainings shared their opinion that Black Americans had no reason to protest. As part of the weeklong session in July 1963, the intelligence unit’s leadership chose to screen Operation Abolition, a propaganda film produced by the House Un-American Activities Committee that claimed that those who opposed its work were Communist subversives intent on fomenting riots and anarchy. NIMH psychologists reported hearing several officers excitedly sharing “fantasies regarding what battle would be like with large crowds of Negroes and whites under riot conditions,” and they noted with concern that “these policemen relished violence and were quite at home in it.”

But the NIMH team also detected a palpable anxiety among the officers as they contemplated the “new, unfamiliar, and unexpected behavior on the part of Negroes” embodied by the march. As one of the psychologists later admitted, his team left the training feeling “slightly defeated, exhausted, and uneasy about how the officers would behave when confronted with a live challenge in the street.”

At least two police departments felt it necessary to dispatch officers to travel far beyond their jurisdictions to monitor events firsthand in Washington. In Philadelphia, Commissioner Howard Leary assigned James Reaves, a Black inspector heading the Police Community Relations Division, to travel to D.C. by himself to attend the event in plainclothes and write a report on what he observed. This was in spite of the more than 50 Philadelphia Guardians who were already attending the event who could have easily shared their impressions of the day with Leary.

But Reaves had a different assignment in Washington. The 47-year-old veteran officer had a long record of working closely with George Fencl, the head of Philadelphia’s intelligence squad, also known as the Civil Disobedience Unit. Among other responsibilities, the CDU was tasked with creating a file card for every demonstrator it could identify at protests in Philadelphia. Reaves later recalled that he initially had his concerns about the march and had been “hesitant to attend for fear of trouble.” Law enforcement justifiably expected violence, Reaves contended years later, because “riots and demonstrations were the order of the day in many urban communities, and the expression ‘long hot summer’ was well understood. Therefore any information on the subject was anxiously sought.” This was a strange rationale for traveling to Washington, essentially a rewriting of history, considering that virtually no urban riots occurred that decade until uprisings in Harlem, Rochester, and Philadelphia erupted in the summer of 1964.

Reaves described in his memoirs his joy in witnessing the march. He was especially glad that “there were no embarrassing incidents to mar the events of the day,” hinting at his fear that the march would somehow reflect unfavorably on Black people. But his positive impression in no way precluded him from sharing his surveillance with police leadership. Upon returning to Philadelphia, he reported to Commissioner Leary how peaceful the march had been, which he concluded was due largely to the security provided by the Guardians.

But Leary, as Reaves recalled, “seemed more interested in who was there, who spoke, and the attitude of the speakers as well as the crowd. He was so impressed that he had me give a verbal report at the following inspectors’ meeting in his office.” Apparently, Philadelphia’s police leadership did not think that the wall-to-wall media coverage of the march sufficed to demystify the day’s activities, so they needed their plainclothes colleague to share the things he had seen that had somehow escaped the notice of thousands of reporters.

In Birmingham, the city’s all-white police department assigned at least one unnamed officer to the march as well, sending him more than 700 miles beyond their city limits to Washington. The surviving documentation for that trip is a cache of 20 surveillance photographs from the march, archived at the Birmingham Public Library, one close-up after another in which the subjects betray no sign of recognition that their picture is being taken.

The photographs provide a window into the racial anxieties of the white Southerner who took them. One shows a Black police officer directing traffic; another shows an interracial couple holding hands, and yet another a Black man and a white woman chatting amiably. All three are sights that were virtually unthinkable in Birmingham.

And yet, ironically, as invasive as the photos are, there’s also a beauty to several of them. In one shot, amid an almost entirely Black crowd massed in front of the Washington Monument, members of Local 144 of the Hotel and Allied Services Union from New York City can be seen listening in rapt concentration to a speaker out of frame. It’s an image that could be easily mistaken for one of the dozens of shots of the crowd taken by storied photographer Leonard Freed.

As it turned out, of course, the March on Washington was free of violence. But for police officers across the country, the very idea of hundreds of thousands of Black people assembling to demand equality was dangerous. No matter how peaceful they were, the objectives of those who marched on Washington made them a threat. The impressive logistics that went into transporting 250,000 people to and from Washington for a day of protest must have alarmed police. Because if organizers could pull that off, they’d have no problem staging demonstrations in other cities. At the root of police’s insistence on spying on the march was a fear that the rally would radicalize its attendees, that the day’s activities in Washington would incite those on the National Mall to organize their own local marches and protests when they returned home.

Today, the march is revered across the political spectrum. Even the right claims it as a shining moment of multiracial democracy in action, praising King’s speech as the ultimate endorsement of colorblind meritocracy. The very police departments that expended so much time and energy surveilling the march now celebrate King and even approvingly repeat his refrain of “I have a dream.” But as law enforcement agencies rush to assure us of their respect for Dr. King, we should not forget that in August 1963 they witnessed the gains made by a national movement against racism with dismay—and they eagerly spied on those who marched on Washington.