‘Unusual’ ancient graves found near Arctic, but no remains discovered inside, study says

Just south of the Arctic Circle, within the vast forests of northern Finland, lies a sandy field dotted with dozens of “unusual” pits.

Workers stumbled upon the site, known as Tainiaro, six decades ago, and since then, its origins have remained elusive.

But now, upon conducting a comprehensive analysis of the site, researchers determined it is likely a sprawling hunter-gatherer cemetery dating back some 6,500 years, according to a study published on Dec. 1 in the journal Antiquity.

“Such a large cemetery at such a high northerly latitude does not necessarily fit preconceptions about prehistoric foragers in this region,” researchers affiliated with Finland’s University of Oulu said, adding it may be time to “recalibrate our expectations.”

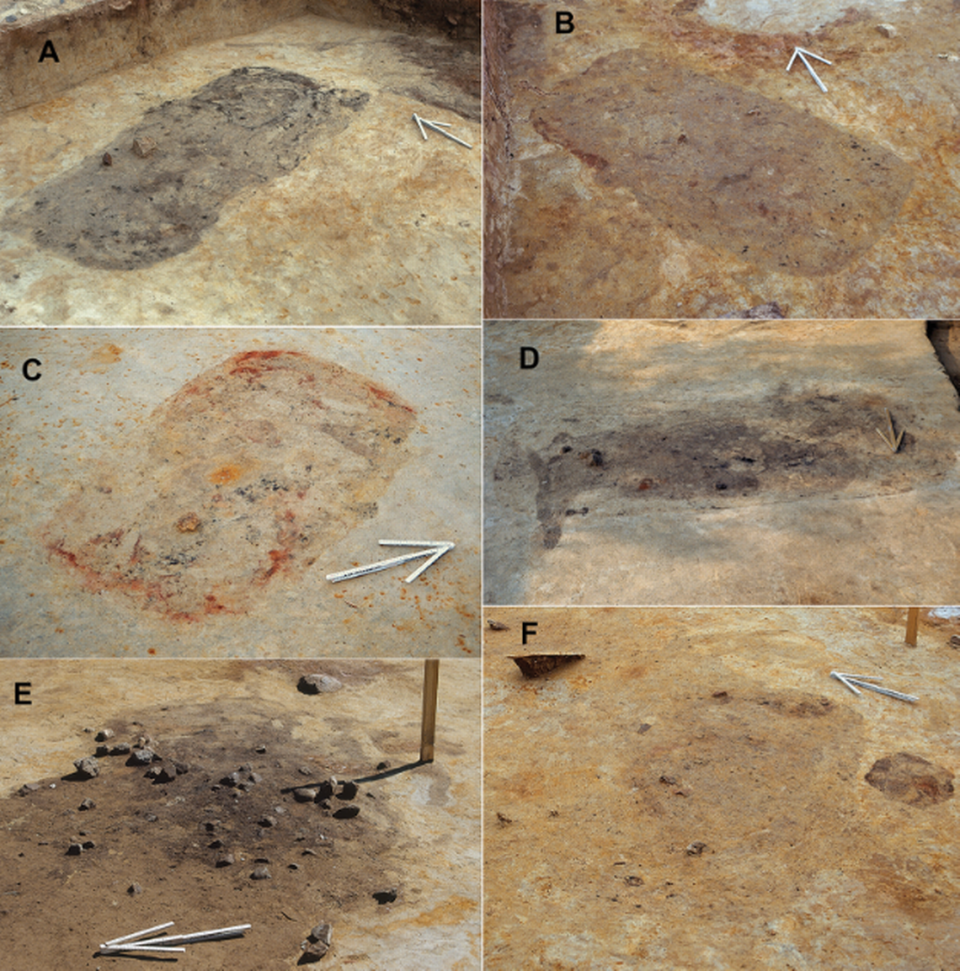

During excavations conducted in 2018 and an analysis of archival fieldwork, researchers identified an estimated 115 to 200 pits. Most were rectangular in shape with dimensions around 7 feet in length and 2.5 feet in depth.

No human remains were found inside, but thousands of artifacts, including pottery, ochre and burned animal bones, were located.

Skillfully-crafted chisels and “hand-sized stones that could be fashioned into smaller bladed tools” were also among the objects found, Aki Hakonen, one of the study authors, told McClatchy News.

By comparing these pits to other Stone Age archaeological findings, researchers concluded that they were likely burial sites used by roaming peoples who would have foraged, hunted and fished in the region.

“Tainiaro should, in our opinion, be considered to be a cemetery site,” researchers said, “even though no skeletal material has survived at Tainiaro.”

Complicating their conclusion, though, was the evidence of burned material found inside some of the pits, suggesting they may have been hearths. However, the traces of charred material were insufficient to prove pyrotechnic use.

This finding, though, indicates the possibility that the site was not solely used for burying the dead.

“Indeed, it has recently been argued that Mesolithic places for the dead were also places for the living and some sites previously interpreted as cemeteries were in fact habitation sites with burials dug beneath the dwellings,” researchers said.

With that possibility in mind, researchers said Tainiaro should not be considered a single-purpose site, but rather it may have served multiple aims.

If it was used, at least partly, as a grave site, it would rank among the most sizable Stone Age cemeteries in northern Europe.

Finland alone has over 200 Stone Age burial sites, most of which are exceedingly small, Hakonen said.

“There are a few sites with around 20 burials, but even these are anomalies,” Hakonen said. “But more than a hundred burials is perplexing, and more than two hundred is astounding.”

The Tainiaro site is particularly astonishing because it’s located in a forbidding sub-Arctic region with heavy winter snowfalls and temperatures that drop below 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

“This is not a place where you’d expect Stone Age foragers to gather in large groups,” Hakonen said. “But perhaps they did.

1,900-year-old winery — that made drinks for ancient Romans — found in France. See it

Ancient trove of gems, coins unearthed at ‘magical place’ in Italy. See the treasures

Monks fled burning monastery during revolt 500 years ago. Now its ruins are unearthed